Ancile

In ancient Rome, the ancilia (Latin, singular ancile) were twelve sacred shields kept in the Temple of Mars. According to legend, one divine shield fell from heaven during the reign of Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome. He ordered eleven copies made to confuse would-be thieves, since the original shield was regarded as one of the pignora imperii (pledges of rule), sacred guarantors that perpetuated Rome as a sovereign entity.

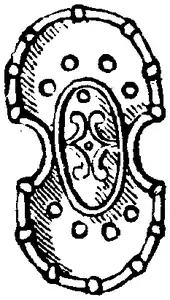

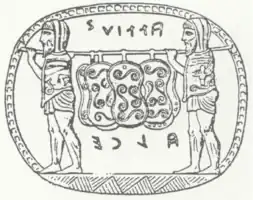

The shields are identified by their distinct 'figure of eight' shape which is said to be derived from Mycenaean art.[1] As described by Plutarch, the shape of the ancile is a standard shield, neither round or oval, which has curved indentations on both sides.[2]

The ancilia were kept by the Salii, a body of twelve priests instituted for that purpose by Numa.[3] The Salii wielded them ritually in a procession throughout March. According to Varro, the ancilia may have also made an appearance in the Armilustrium (‘Purification of the Arms’) in October.[4] The Salii were said to beat their shields with staves while performing ritual dances and singing the Carmen Salire.[5]

Etymology

Ancient sources give varying etymologies for the word ancile. Some derive it from the Greek ankylos (ἀγκύλος), "crooked". Plutarch thinks the word may be derived from the Greek ankōn (ἀγκών), "elbow", the weapon being carried on the elbow. Varro derives it ab ancisu, as being cut or arched on the two sides, like the bucklers of the Thracians called peltae.

Myth

When the original ancile fell, a voice was heard which declared that Rome should be mistress of the world while the shield was preserved. The shield was said to have been sent down from heaven by Jupiter to Numa. The Ancile was, as it were, the palladium of Rome. Numa, by the advice, as it is said, of the nymph Egeria, ordered eleven others, perfectly like the first, to be made. This was so that if anyone should attempt to steal it, as Ulysses did the Palladium, they might not be able to distinguish the true Ancile from the false ones. According to Ovid’s Fasti, Mamurius Veturius agreed to forge the eleven replicas of the original ancile if he was given glory by Numa and mentioned in the Carmen Salire.[6] Thus, this myth provides the etiological story for the Cult of Mamurius which was popular in the Augustan Age.[7] The gifting of the ancile to Numa is viewed as a legend which reveals a successful and favorable interaction Numa had with Jupiter.[8]

Ancile as Pignora Imperii

Maurus Servius Honoratus, an early 4th century grammarian, regards the ancile as one of the seven pignora imperii of the Roman empire in his In Vergilii Aeneidem commentarii (‘Commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid’). Alongside the ancile, Servius lists the other six pignora: the stone of the Mother of the Gods, the terracotta chariot of the Veientines, the ashes of Orestes, the sceptre of Priam, the veil of Iliona, and the palladium.[9][10] Livy mentions the ancilia as a passing reference again in book 5 of Ab Urbe Condita, but does not directly assign the label of pignus imperii to the ancilia. He only assigns this label to the Palladium and the eternal flame of Vesta.[11]

References

- Howatson, M. C. HowatsonM C. (2011-01-01), Howatson, M. C. (ed.), "ancī'lia", The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-954854-5, retrieved 2022-11-30

- Plutarch (1914). Lives, Volume I: Theseus and Romulus. Lycurgus and Numa. Solon and Publicola. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:20

- Varro (1938). On the Latin Language, Volume I: Books 5-7. Translated by Kent, Roland G. Harvard University Press. p. 6.22.

- Bailey, Cyril; North, J. A. (2005), "Salii", The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198606413.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-860641-3, retrieved 2022-11-30

- Ovid (2006), Littlewood, R. Joy (ed.), "Fasti", A Commentary on Ovid: Fasti Book III, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00089826, ISBN 978-0-19-927134-4, retrieved 2022-11-30

- Praet, Raf (2016). "Re-anchoring Rome's Protection in Constantinople : The 'pignora imperii' in Late Antiquity and Byzantium". Sacris Erudiri. 55: 277–319. doi:10.1484/j.se.5.112604. ISSN 0771-7776.

- Luke, Trevor (2014). "Augustus as the New Numa". Ushering in a New Republic. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. p. 244. doi:10.3998/mpub.6265337. ISBN 978-0-472-07222-4.

- Maurus Honoratus, Servius. In Vergilii Aeneidem commentarii. pp. ad Aen. 7, 188.

- Balbuza, Katarzyna (2018). "Livy and the pignora imperii. The Historian from Patavium as a Eulogist of the Idea of the Eternity of Rome". In Gillmeister, Andrzej (ed.). Rerum gestarum monumentis et memoriae: Cultural Readings in Livy. pp. 127–136.

- Livy (1924). History of Rome, Volume III: Books 5-7. Translated by Foster, B. O. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Ancile". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Ancile". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.