Origins of Judaism

The origins of Judaism lie in Bronze Age polytheistic Canaanite religion. It also syncretized elements of other Semitic religions such as Babylonian religion, which is reflected in the early prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible.[6]

| Judaism | |

|---|---|

| יַהֲדוּת Yahadut | |

| |

| Type | Ethnic religion[1] |

| Classification | Abrahamic |

| Scripture | Hebrew Bible |

| Theology | Monotheistic |

| Leaders | Jewish leadership |

| Movements | Jewish religious movements |

| Associations | Jewish religious organizations |

| Region | Predominant religion in Israel and widespread worldwide as minorities |

| Language | Biblical Hebrew[2] |

| Headquarters | Jerusalem (Zion) |

| Founder | Abraham[3][4] (traditional) |

| Origin | 1st millennium BCE 20th–18th century BCE[3] (traditional) Judah Mesopotamia[3] (traditional) |

| Separated from | Yahwism |

| Congregations | Jewish religious communities |

| Members | c. 14–15 million[5] |

| Ministers | Rabbis |

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

During the Iron Age I, the Israelite religion branched out of the Canaanite religion through Yahwism. Yahwism was the national religion of the Kingdom of Israel and Kingdom of Judah.[7] Compared to other Canaanite religious traditions, Yahwism was monolatristic and focused on the exclusive worship of Yahweh, who was conflated with El. [8]The existence of other gods, whether Canaanite or foreign, was denied as Yahwism became more strictly monotheistic. [9][10]

During the Babylonian captivity of the 6th and 5th centuries BCE (Iron Age II), certain circles within exiled Judahites in Babylon refined pre-existing ideas about Yahwism, such as the nature of divine election, law and covenants. Their ideas dominated the Jewish community in the following centuries.[11]

From the 5th century BCE until 70 CE, Yahwism evolved into the various theological schools of Second Temple Judaism, besides Hellenistic Judaism in the diaspora. Second Temple Jewish eschatology has similarities with Zoroastrianism.[12] The text of the Hebrew Bible was redacted into its extant form in this period and possibly also canonized as well. Archaeological and textual evidence pointing to widespread observance of the laws of the Torah among rank-and-file Jews first appears around the middle of the 2nd century BCE, during the Hasmonean period.[13]

Rabbinic Judaism developed in Late Antiquity, during the 3rd to 6th centuries CE; the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud were compiled in this period. The oldest manuscripts of the Masoretic tradition come from the 10th and 11th centuries CE, in the form of the Aleppo Codex of the later portions of the 10th century CE and the Leningrad Codex dated to 1008–1009 CE. Due largely to censoring and the burning of manuscripts in medieval Europe, the oldest existing manuscripts of various rabbinical works are quite late. The oldest surviving complete manuscript copy of the Babylonian Talmud is dated to 1342 CE.[14]

Iron Age Yahwism

Judaism has three essential and related elements: study of the written Torah (the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy); the recognition of Israel (defined as the descendants of Abraham through his grandson Jacob) as a people elected by God as recipients of the law at Mount Sinai, his chosen people; and the requirement that Israel live in accordance with God's laws as given in the Torah.[15] These have their origins in Iron Age Yahwism and in Second Temple Judaism.[16]

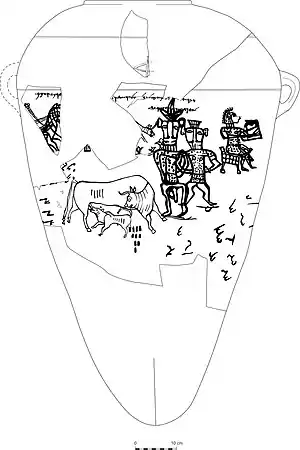

Iron Age Yahwism was formalized in the 9th century BCE, around the same time the Iron Age kingdoms of Israel (or Samaria) and Judah were established in Canaan.[17][18] Yahweh was the national god of both kingdoms. [7]

Other neighbouring Canaanite kingdoms also had their own national god from the Canaanite pantheon of gods: Chemosh was the god of Moab, Milcom the god of the Ammonites, Qaus the god of the Edomites, and so on. In each kingdom, the king was his national god's viceroy on Earth.[7][19][20]

The various national gods were more or less equal, reflecting the fact that kingdoms themselves were more or less equal, and within each kingdom a divine couple, made up of the national god and his consort – Yahweh and the goddess Asherah in Israel and Judah – headed a pantheon of lesser gods.[18][21][9]

By the late 8th century, both Judah and Israel had become vassals of Assyria, bound by treaties of loyalty on one side and protection on the other. Israel rebelled and was destroyed c. 722 BCE, and refugees from the former kingdom fled to Judah, bringing with them the tradition that Yahweh, already known in Judah, was not merely the most important of the gods, but the only god who should be served. This outlook was taken up by the Judahite landowning elite, who became extremely powerful in court circles in the next century when they placed the eight-year-old Josiah (reigned 641–609 BC) on the throne. During Josiah's reign, Assyrian power suddenly collapsed, and a pro-independence movement took power promoting both the independence of Judah from foreign overlords and loyalty to Yahweh as the sole god of Israel. With Josiah's support, the "Yahweh-alone" movement launched a full-scale reform of worship, including a covenant (i.e., treaty) between Judah and Yahweh, replacing that between Judah and Assyria.[22]

By the time this occurred, Yahweh had already been absorbing or superseding the positive characteristics of the other gods and goddesses of the pantheon, a process of appropriation that was an essential step in the subsequent emergence of one of Judaism's most notable features: its uncompromising monotheism.[21] The people of ancient Israel and Judah, however, were not followers of Judaism; they were practitioners of a polytheistic culture worshiping multiple gods, concerned with fertility and local shrines and legends, and not with a written Torah, elaborate laws governing ritual purity, or an exclusive covenant and national god.[23]

Second Temple Judaism

In 586 BCE, Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonians, and the Judean elite – the royal family, the priests, the scribes, and other members of the elite – were taken to Babylon in captivity. They represented only a minority of the population, and Judah, after recovering from the immediate impact of war, continued to have a life not much different from what had gone before. In 539 BCE, Babylon fell to the Persians; the Babylonian exile ended and a number of the exiles, but by no means all and probably a minority, returned to Jerusalem. They were the descendants of the original exiles, and had never lived in Judah; nevertheless, in the view of the authors of the Biblical literature, they, and not those who had remained in the land, were "Israel".[24] Judah, now called Yehud, was a Persian province, and the returnees, with their Persian connections in Babylon, were in control of it. They represented also the descendants of the old "Yahweh-alone" movement, but the religion they instituted was significantly different from both monarchic Yahwism[6] and modern Judaism. These differences include new concepts of priesthood, a new focus on written law and thus on scripture, and a concern with preserving purity by prohibiting intermarriage outside the community of this new "Israel".[6]

The Yahweh-alone party returned to Jerusalem after the Persian conquest of Babylon and became the ruling elite of Yehud. Much of the Hebrew Bible was assembled, revised and edited by them in the 5th century BCE, including the Torah (the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), the historical works, and much of the prophetic and Wisdom literature.[25][26] The Bible narrates the discovery of a legal book in the Temple in the seventh century BCE, which the majority of scholars see as some form of Deuteronomy and regard as pivotal to the development of the scripture.[27] The growing collection of scriptures was translated into Greek in the Hellenistic period by the Jews of the Egyptian diaspora, while the Babylonian Jews produced the court tales of the Book of Daniel (chapters 1–6 of Daniel – chapters 7–12 were a later addition), and the books of Tobit and Esther.[28]

Widespread adoption of Torah law

In his seminal Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels, Julius Wellhausen argued that Judaism as a religion based on widespread observance Torah law first emerged in 444 BCE when, according to the biblical account provided in the Book of Nehemiah (chapter 8), a priestly scribe named Ezra read a copy of the Mosaic Torah before the populace of Judea assembled in a central Jerusalem square.[29] Wellhausen believed that this narrative should be accepted as historical because it sounds plausible, noting: "The credibility of the narrative appears on the face of it."[30] Following Wellhausen, most scholars throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries have accepted that widespread Torah observance began sometime around the middle of the 5th century BCE.

More recently, Yonatan Adler has argued that in fact there is no surviving evidence to support the notion that the Torah was widely known, regarded as authoritative, and put into practice, any time prior to the middle of the 2nd century BCE.[13] Adler explored the likelihhood that Judaism, as the widespread practice of Torah law by Jewish society at large, first emerged in Judea during the reign of the Hasmonean dynasty, centuries after the putative time of Ezra.[31]

Development of Rabbinic Judaism

For centuries, the traditional understanding has been that the split of early Christianity and Judaism some time after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE was the first major theological schism in Jewish tradition. Starting in the latter half of the 20th century, some scholars have begun to argue that the historical picture is quite a bit more complicated than that.[32][33]

By the 1st century, Second Temple Judaism was divided into competing theological factions, notably the Pharisees and the Sadducees, besides numerous smaller sects such as the Essenes, messianic movements such as Early Christianity, and closely related traditions such as Samaritanism (which gives us the Samaritan Pentateuch, an important witness of the text of the Torah independent of the Masoretic Text). The sect of Israelite worship that eventually became Rabbinic Judaism and the sect which developed into Early Christianity were but two of these separate Israelite religious traditions. Thus, some scholars have begun to propose a model which envisions a twin birth of Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, rather than an evolution and separation of Christianity from Rabbinic Judaism. It is increasingly accepted among scholars that "at the end of the 1st century CE there were not yet two separate religions called 'Judaism' and 'Christianity'".[34] Daniel Boyarin (2002) proposes a revised understanding of the interactions between nascent Christianity and nascent Rabbinic Judaism in Late Antiquity which views the two religions as intensely and complexly intertwined throughout this period.

The Amoraim were the Jewish scholars of Late Antiquity who codified and commented upon the law and the biblical texts. The final phase of redaction of the Talmud into its final form took place during the 6th century CE, by the scholars known as the Savoraim. This phase concludes the Chazal era foundational to Rabbinical Judaism.

See also

- Atenism, the two-decade duration ancient Egyptian monotheistic religion of the 14th century BCE

- Hellenistic religion

- Historicity of the Bible

- Jewish history

- Jewish studies

- Maccabees

- Old Testament theology

- Religions of the ancient Near East

References

Citations

- Jacobs 2007, p. 511 quote: "Judaism, the religion, philosophy, and way of life of the Jews.".

- Sotah 7:2 with vowelized commentary (in Hebrew). New York. 1979. Retrieved Jul 26, 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mendes-Flohr 2005.

- Levenson 2012, p. 3.

- Dashefsky, Arnold; Della Pergola, Sergio; Sheskin, Ira, eds. (2018). World Jewish Population (PDF) (Report). Berman Jewish DataBank. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- Moore & Kelle 2011, p. 402.

- Hackett 2001, p. 156.

- Smith 2002, pp. 8, 33–34.

- Betz 2000, p. 917.

- Albertz 1994, p. 61.

- Gnuse 1997, p. 225.

- "Diseases in Jewish Sources". Encyclopaedia of Judaism. doi:10.1163/1872-9029_ej_com_0049. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- Adler 2022.

- Golb, Norman (1998). The Jews in Medieval Normandy: A Social and Intellectual History. Cambridge University Press. p. 530. ISBN 978-0521580328.

- Neusner 1992, p. 3.

- Neusner 1992, p. 4.

- Schniedewind 2013, p. 93.

- Smith 2010, p. 119.

- Davies 2010, p. 112.

- Miller 2000, p. 90.

- Anderson 2015, p. 3.

- Rogerson 2003, p. 153-154.

- Davies 2016, p. 15.

- Moore & Kelle 2011, p. 397.

- Coogan et al. 2007, p. xxiii.

- Berquist 2007, p. 3-4.

- Frederick J. Murphy (15 April 2008). "Second Temple Judaism". In Alan Avery-Peck (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Judaism. Jacob Neusner. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-470-75800-7.

- Coogan et al. 2007, p. xxvi.

- Wellhausen 1885, p. 405–410.

- Wellhausen 1885, p. 408 n. 1.

- Adler 2022, p. 223–234.

- Becker & Reed 2007.

- Dunn, James D. G., ed. (1999). Jews and Christians: the parting of the ways A.D. 70 to 135. William B Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802844989.

- Goldenberg, Robert (2002). "Reviewed Work: Dying for God: Martyrdom and the Making of Christianity and Judaism by Daniel Boyarin". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 92 (3/4): 586–588. doi:10.2307/1455460. JSTOR 1455460.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Susan (2003). "Goddesses". In Richard, Suzanne (ed.). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

- Adler, Yonatan (2022). The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300254907.

- Ahlstrom, Gosta W. (1991). "The Role of Archaeological and Literary Remains in Reconstructing Israel's History". In Edelman, Diana Vikander (ed.). The Fabric of History: Text, Artifact and Israel's Past. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567491107.

- Albertz, Rainer (2003). "Problems and Possibilities: Perspectives on Postexilic Yahwism". In Albertz, Rainer; Becking, Bob (eds.). Yahwism After the Exile: Perspectives on Israelite Religion in the Persian Era. Uitgeverij Van Gorcum. ISBN 9789023238805.

- Albertz, Rainer (1994). A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227197.

- Allen, Spencer L. (2015). The Splintered Divine: A Study of Istar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East. De Gruyter. ISBN 9781501500220.

- Anderson, James S. (2015). Monotheism and Yahweh's Appropriation of Baal. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567663962.

- Becker, A. H.; Reed, A. Y. (2007). The Ways that Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0343-5.

- Becking, Bob (2001). "The Gods in Whom They Trusted". In Becking, Bob (ed.). Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841271996.

- Bennett, Harold V. (2002). Injustice Made Legal: Deuteronomic Law and the Plight of Widows, Strangers, and Orphans in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825742.

- Berquist, Jon L. (2007). Approaching Yehud: New Approaches to the Study of the Persian Period. SBL Press. ISBN 9781589831452.

- Betz, Arnold Gottfried (2000). "Monotheism". In Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9053565035.

- Chalmers, Aaron (2012). Exploring the Religion of Ancient Israel: Prophet, Priest, Sage and People. SPCK. ISBN 9780281069002.

- Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1999). "The Temple and the Synagogue". In Finkelstein, Louis; Davies, W. D.; Horbury, William (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 3, The Early Roman Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243773.

- Cohn, Norman (2001). Cosmos, Chaos, and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300090889.

- Collins, John J. (2005). The Bible After Babel: Historical Criticism in a Postmodern Age. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802828927.

- Coogan, Michael D.; Smith, Mark S. (2012). Stories from Ancient Canaan (2nd ed.). Presbyterian Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-9053565032.

- Cook, Stephen L. (2004). The Social Roots of Biblical Yahwism. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830981.

- Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, M. Z.; Newsom, C. A.; Perkins, P. (2007). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-528880-3.

- Darby, Erin (2014). Interpreting Judean Pillar Figurines: Gender and Empire in Judean Apotropaic Ritual. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161524929.

- Davies, Philip R.; Rogerson, John (2005). The Old Testament World. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780567084880.

- Davies, Philip R. (2016). The Origins of Judaism. Routledge. ISBN 9781134945023.

- Davies, Philip R. (2010). "Urban Religion and Rural Religion". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John (eds.). Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567032164.

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series. Vol. 265. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780826468307.

- Dever, William G. (2003a). "Religion and Cult in the Levant". In Richard, Suzanne (ed.). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

- Dever, William G. (2003b). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802844163.

- Dever, William G. (2005). Did God Have A Wife?: Archaeology And Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2852-1.

- Dicou, Bert (1994). Edom, Israel's Brother and Antagonist: The Role of Edom in Biblical Prophecy and Story. A&C Black. ISBN 9781850754589.

- Dijkstra, Meindert (2001). "El the God of Israel-Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism". In Becking, Bob; Dijkstra, Meindert; Korpel, Marjo C.A.; et al. (eds.). Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841271996.

- Edelman, Diana Vikander (1995). "Tracking Observance of the Aniconic Tradition". In Edelman, Diana Vikander (ed.). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9053565035.

- Elior, Rachel (2006). "Early Forms of Jewish Mysticism". In Katz, Steven T. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521772488.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743223386.

- Freedman, D. N.; O'Connor, M. P.; Ringgren, H. (1986). "YHWH". In Botterweck, G. J.; Ringgren, H. (eds.). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol. 5. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802823298.

- Frerichs, Ernest S. (1998). The Bible and Bibles in America. Scholars Press. ISBN 9781555400965.

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series. Vol. 241. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567374158.

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1999). "The Emergence of Monotheism in Ancient Israel: A Survey of Recent Scholarship". Religion. 29 (4): 315–336. doi:10.1006/reli.1999.0198.

- Gorman, Frank H., Jr. (2000). "Feasts, Festivals". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grabbe, Lester (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567455017.

- Grabbe, Lester (2010). "'Many nations will be joined to YHWH in that day': The question of YHWH outside Judah". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John (eds.). Religious diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-03216-4.

- Grabbe, Lester (2007). Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567032546.

- Hackett, Jo Ann (2001). "'There Was No King in Israel': The Era of the Judges". In Coogan, Michael David (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- Halpern, Baruch; Adams, Matthew J. (2009). From Gods to God: The Dynamics of Iron Age Cosmologies. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161499029.

- Handy, Lowell K. (1995). Among the Host of Heaven: The Syro-Palestinian Pantheon as Bureaucracy. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464843.

- Hess, Richard S. (2007). Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801027178.

- Hess, Richard S. (2020). "Israelite Religion". In Barton, John (ed.). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.156. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8.

- Humphries, W. Lee (1990). "God, Names of". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- Keel, Othmar (1997). The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060149.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-097-4.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227272.

- Levenson, Jon Douglas (2012). Inheriting Abraham: the legacy of the patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16355-0.

- Levin, Christoph (2013). Re-Reading the Scriptures: Essays on the Literary History of the Old Testament. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161522079.

- Liverani, Mario (2014). Israel's History and the History of Israel. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317488934.

- Mafico, Temba L. J. (1992). "The Divine Name Yahweh Alohim from an African Perspective". In Segovia, Fernando F.; Tolbert, Mary Ann (eds.). Reading from this Place: Social Location and Biblical Interpretation in Global Perspective. Vol. 2. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451407884.

- Mastin, B. A. (2005). "Yahweh's Asherah, Inclusive Monotheism and the Question of Dating". In Day, John (ed.). In Search of Pre-Exilic Israel. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567245540.

- Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2006). "A Conversation with My Critics: Cultic Image or Aniconism in the First Temple?". In Amit, Yaira; Naʼaman, Nadav (eds.). Essays on Ancient Israel in Its Near Eastern Context. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061283.

- Meyers, Carol (2001). "Kinship and Kingship: The early Monarchy". In Coogan, Michael David (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- MacDonald, Nathan (2007). "Aniconism in the Old Testament". In Gordon, R. P. (ed.). The God of Israel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521873659.

- Miller, Patrick D. (2000). The Religion of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22145-4.

- Miller, James M.; Hayes, John H. (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664212629.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802862600.

- Neusner, Jacob (1992). A Short History of Judaism. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451410181.

- Niehr, Herbert (1995). "The Rise of YHWH in Judahite and Israelite Religion". In Edelman, Diana Vikander (ed.). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9053565035.

- Noll, K. L. (2001). Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841272580.

- Petersen, Allan Rosengren (1998). The Royal God: Enthronement Festivals in Ancient Israel and Ugarit?. A&C Black. ISBN 9781850758648.

- Rogerson, John W. (2003). "Deuteronomy". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John W. (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Schniedewind, William M. (2013). A Social History of Hebrew: Its Origins Through the Rabbinic Period. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300176681.

- Smith, Mark S. (2000). "El". In Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Smith, Mark S. (2001). The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195167689.

- Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802839725.

- Smith, Mark S. (2003). "Astral Religion and the Divinity". In Noegel, Scott; Walker, Joel (eds.). Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World. Penn State Press. ISBN 0271046007.

- Smith, Mark S. (2010). God in Translation: Deities in Cross-Cultural Discourse in the Biblical World. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802864338.

- Smith, Mark S. (2017). "YHWH's Original Character: Questions about an Unknown God". In Van Oorschot, Jürgen; Witte, Markus (eds.). The Origins of Yahwism. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Vol. 484. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-042538-3.

- Smith, Morton (1984). "Jewish Religious Life in the Persian Period". In Finkelstein, Louis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 1, Introduction: The Persian Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521218801.

- Sommer, Benjamin D. (2011). "God, Names of". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine L. (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199730049.

- Vanderkam, James C. (2022). An Introduction to Early Judaism (2nd ed.). Eerdmans. ISBN 978-1-4674-6405-5.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1995). "Ritual Resistance and Self-Assertion". In Platvoet, Jan. G.; Van der Toorn, Karel (eds.). Pluralism and Identity: Studies in Ritual Behaviour. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9004103732.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1999). "Yahweh". In Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem (eds.). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9004104100.

- Vriezen, T. C.; van der Woude, Simon Adam (2005), Ancient Israelite And Early Jewish Literature, translated by Doyle, Brian, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-12427-1

- Wellhausen, Julius (1885). Prolegomena to the History of Israel. Black. ISBN 9781606202050.

- Wyatt, Nicolas (2010). "Royal Religion in Ancient Judah". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John (eds.). Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-03216-4.

External links

- Adler, Yonatan (16 February 2023). "When Did Jews Start Observing Torah? – TheTorah.com". thetorah.com. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Amzallag, Nissim (August 2018). "Metallurgy, the Forgotten Dimension of Ancient Yahwism". The Bible and Interpretation. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- Brown, William, ed. (October 2017). "Early Judaism". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- Gaster, Theodor H. (26 November 2020). "Biblical Judaism (20th–4th century BCE)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 28 July 2021.