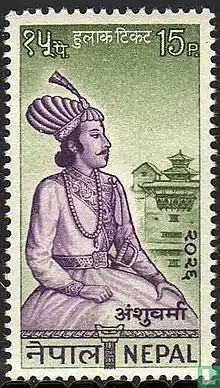

Amshuverma

Amshuverma or Amshu Verma (Nepali: अंशुवर्मा) was a king of Nepal from around 605–621 CE. Initially a feudal lord, he rose to the position of Mahasamanta (equivalent to prime minister) in about 598 CE when Shivadeva I of the Licchavi dynasty was the ruling monarch and by 604, Shivadeva was reduced to a mere figurehead. He is considered to have died in 621 AD and was succeeded by Udaydeva, the son of Shivadeva I.[1]

| Amshuverma | |

|---|---|

| Pashupati Bhattarak, Mahasamanta of the Licchavis | |

Statue of Amshuverma at the Chhauni Museum, Kathmandu | |

| King of Nepal | |

| Reign | 605–621 |

| Predecessor | Shivadeva I |

| Successor | Udaydeva |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Life

Amshuverma took the title of Pashupati Bhattarak being in Shaivite majority period.[2] The meaning of Sanskrit word Bhattaraka is leaders of religious orders in Shaivism. He is believed to have been a son of a brother of the queen of Sivadeva. He was learned, bold and farsighted ruler of Lichhavi period, he was also a lover of art, architecture and literature. He built Kailashkut Bhawan palace, which became famous as a state of the art palace south of the Himalayas in the seventh century.[3]

The Chinese ambassador Wang Huen Che who was appointed about 640 AD makes a graphic description of its grandeur in Tang Annals of China.[3] The appointment of the Chinese ambassador to the court of Nepal in seventh century shows that a very close relationship pertained between Nepal and China already.

Many Tibetan accounts make Bhrikuti the daughter of Amshuverma. If this is correct, the marriage to Songtsän Gampo must have taken place sometime before 624 CE.[4] Acharya Kirti Tulku Lobsang Tenzin, however, states that Songstän Gampo married Bhrkuti Devi, the daughter of king "Angsu Varma" or Amshuvarma (Tib: Waser Gocha) of Nepal in 632.[5]

According to some Tibetan legends, however, a Nepali king named Go Cha (identified by Sylvain Lévi as "Udayavarman", from the literal meaning of the Tibetan name) was said to have a daughter called Bri-btumn or Bhṛkuti.[3] "Udayavarman" was most likely the same king we know as Udaydeva, the son of Shivadeva I and later, the adopted son and heir to Aṃshuvarmā. He was also thought to be the father of Narendradeva (Tib: Miwang-Lha).[6] If this is accepted, it means that Narendradeva and Bhrikuti Devi were brother and sister.

It is believed that Udayadev was exiled to Tibet and his daughter, Bhrikuti, was married to the Tibet Emperor Tsrong-tsang Gompo. This event appears to have opened trade routes between Nepal and Tibet. Some early historians in Nepal had mistakenly concluded that the pictographic symbol used to name the father of Bhrikuti in Tang Annals stood for Amshu (which means the rays of the rising sun in Sanskrit, the language used in Nepal then), where as Udaya (the rise of the sun) would also be written with the same symbols. Bhrikuti could not have been Amshuverma's daughter simply because she would be too old to marry the Tibet Emperor. Bhrikuti was daughter of Udayadev and she had dispatched the Tibetan army to Nepal valley to reinstate Narendradev, her brother, as king in Nepal about 640 AD. Bhrikuti was instrumental in spreading Buddhism to Tibet and she later attained the status of Tara, the shakti in Mahayana Buddhism.

The Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who visited India during the 7th century, described Aṃshuvarmā as a man of many talents.[3][1] The original temple of Jokhang in Lhasa was modeled after a Nepali monastery design - a square quadrangle with the kwa-pa-dyo shrine at the center of the east wing, opposite to the entrance. The innermost shrine room of the world heritage Jokhang temple still displays the woodwork of Nepali origin and craftsmanship. Since then, and specially after the contributions of Araniko, a Nepali bronze caster and architect who was sent to Tibet to cast a stupa in 1265 AD, Nepali art and architecture spread over the countries like China and Japan. An inscription by Aṃshuvarmā dated to 607 AD at Tistung professes the importance of the "Aryan code of conduct" (i.e. the caste system).

A great feat of architecture and engineering, the Kailashkut Bhawan, is believed to have been located about Hadigaun in Kathmandu. It had three courtyards and seven storied tiered structure with grand water works and inlay stone decorations. Amshuverma also introduced the second Licchavi era (samvat). Economically, Nepal was much developed during his time. His ruling period is known as the 'Golden Period' in the history of Nepal.[3][1]

Amshuverma's sister, Bhoga Devi, was married to an Indian king, Sur Sen; this marriage helped Amshuvera strengthen Nepal's relationship with India. He maintained the independence and sovereignty of Nepal by his successful foreign policy.

His Sanskrit grammar, entitled Shabda Vidya, made him popular even outside the nation. The famous Chinese traveller Huen Tsang praised him in his travel account.

Amshuverma's regime became a boon to the Licchavi Period so that it came to be called a golden age. He has become immortal in the history of Nepal.

Most of the inscriptions of king Shivadeva I, there is the name of Amshuverma as Srimahasamanta. In the later period of king Shivadeva I, Amshuverma coupe and declared himself sovereign ruler.[1] King Shivadev fled from the palace with his family to neighboring country Tibet because they were all Buddhist kings and very close in trade relation. While in Tibet, for several years, Shivadeva I's daughter Virkuti was married to a Tibetain prince. King Shong Chog Gombus' second wife was the daughter of Tang king Taizong. During this time, Amshuverma changed three different positions: Shri- mahsamanta from a seven storied building Kailashkut royal palace at Hadigaon, Shree Amshuverma issued the crescent symbolic coins minted in his name, Sri-maharajadhiraja from the last time of his rule.[1] In one inscription issued by his queen, Amshuverma is addressed as Sri-kalhabhimani (lover of goddess of knowledge, music, art, speech, wisdom, and learning). The work Shabdavidya (grammar) is the literary creation of Amshuverma in his 26 years of ruling period. He adored his clan as Bappa-pada-nudhyat (blessed by predecessors).

Sources of the family of Amshuverma are silent and there was marital relation between the Deva and Verma clans. Amshuverma was the man of diplomatic experiments and a successful political benefiter to exploit the situation to grab state power at any means. He welcomed scholars in his state and was in favor of local self-government for welfare of the people. Nepal had trade relations with Tibet and the items exchanged were iron, yak tail, wool, musk deer pod, copper utensils, and herbs. In 618AD there was economic relation with Tibet and Tibet started to encroach towards Nepal when it absorbed more power which is noticed by the Gopalaraj Vamsavali. In the south, Nepal had trade as well as diplomatic relations with Bidharvaraj Harshaverdhan, was a powerful king of Kanauj. Prince Surasen of Kanauj, (Maukhari clan) was the sister in-law of Amshuverma. When Harshaverdhana captured and annexed Kanauj, Surasena came to Nepal and bikramsen was Sarvadandanayak of Amshuverma's court.

Amshuverma was succeeded by Udayadeva, the son of king Shivadeva I.[1] Udayadeva was later dethroned by his younger brother, Dhrubadeva with the help of Jishnu Gupta.[3][1]

Personality

Amshuverma had been acknowledged as a person of talents devoted to the study of the Sastras. According to one inscription where he is addressed as अनिशिनिशिचानेकशास्त्रार्थविमर्शव दिता सद्दर्शन तया धर्माधिकार स्थितिकावोत्सव मनतिश्यम् मन्यमानो [8] and अनन्य नरपति सुकरा पुगयाधिकार स्थिति निबन्धनो नीयमान समाधानो [9] which describe Amshuverma as a person who had purified his mind by incessant pursuit of learning and debates day and night, which had enabled him to frame rules to uphold justice and virtue in the society, a fact he valued most and whose mind was at rest because he had been able to evolve rules of conduct, and maintain justice.[10]

In his reign, a certain Bibhubarma Rajbansi, or descendant of a Rajah, having consecrated a Buddha, built an aqueduct with seven spours, and wrote the following on the right hand side of one of them, " By the kindness of Amshuverma, this aqueduct has been built by Bibhubarma , to augment the merit of his father. " [11]

Pilgrimage

It is usually believed that, Amshuverma was endowed with all the kingly qualities and virtues. He was a just, impartial and an able administrator. He was a true servant of the people without any political bias.[1]

According to some inscriptions, King Shiva Deva used to say that Amshuverma was a man of universal fame and he always destroyed his enemies by his heroic nature. Some other inscriptions tell us that he had a great personality, who dispelled darkness by the light of his glory. Huen Tsang, himself a learned man and respected scholar, writes about him as a man of high accomplishments and great glory.

Amshuverma had written a book on grammar in Sanskrit. The great grammarian Chandraverma, a scholar of Nalanda University, was patronized by him. He followed Shaivism but was tolerant towards all other religions. He can rightly be compared with other great rulers of his time as regards his political outlook and impartial feelings without any religious prejudices. For the development of economic condition of the people he paid great attention to the improvement of trade and commerce of the country. Nepal had trade relations with India, Tibet and China and became the thoroughfare of India's trade with China and vice versa.

Amshuverma gave equal importance to industrial advancement and agricultural prosperity. He made every effort to help the people by providing canals to irrigate the fields. He levied a water tax, a land tax, a defense tax and a luxury tax, using the income from these sources for the development works of the country and not for his personal pleasure and luxury.

References

- Shrestha, D.B. (1972). The History of Ancient and Medieval Nepal (PDF). University of Cambridge.

- Dor Bahadur Bista (1991). Fatalism and Development: Nepal's Struggle for Modernization. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0188-1.

- Shaha, Rishikesh. Ancient and Medieval Nepal. (1992), p. 18. Manohar Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85425-69-8.

- Ancient Tibet: Research materials from the Yeshe De Project, p. 225 (1986). Dharma Publishing, Berkeley, California. ISBN 0-89800-146-3.

- Tenzin, Ahcarya Kirti Tulku Lobsang. "Early Relations between Tibbet and Nepal (7th to 8th Centuries)." Translated by K. Dhondup. The Tibet Journal, Vol. VII, Nos. 1 &2. Spring/Summer 1982, p. 85.

- Shaha, Rishikesh. Ancient and Medieval Nepal. (1992), p. 17. Manohar Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85425-69-8.

- Smith, Vincent Arthur; Edwardes, S. M. (Stephen Meredyth) (1924). The early history of India : from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan conquest, including the invasion of Alexander the Great. Oxford : Clarendon Press. p. Plate 2.

- Gnoli, XLI.

- Gnoli, XLII

- Regmi, D R (1965). Ancient Nepal. Delhi: Rupa. pp. 172, 173, 174, 178. ISBN 81-291-1098-9.

- Singh, Munshi Shew Shunker (2004). History of Nepal. Delhi: Low Price Publications. p. 89. ISBN 81-7536-347-9.