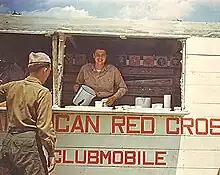

American Red Cross Clubmobile Service

The American Red Cross Clubmobile Service was a mobile service club created during World War II staffed by American Red Cross volunteers, often referred to as "Clubmobile girls" or "Donut Dollies," who provided servicemen with food, entertainment, and "a connection to home."[1][2] Prominent New York Banker and American Red Cross Commissioner to Great Britain, Harvey D. Gibson, conceived of the Clubmobile Service to provide dispersed troops stationed in Great Britain and on European battlefronts with access to the services typical of the recreational clubs found in large cities.[1][3] The Clubmobile was a "single-decker bus fitted with coffee and doughnut-making equipment" as well as "chewing gum, cigarettes, magazines, newspaper, a phonograph, and vinyls."[3] The services provided by the Clubmobile were free, although some Clubmobiles began charging for food after 1942.[4] The original Clubmobiles operated from late 1942 until 1946, traveling throughout Great Britain and Europe.

A brief history

The first Clubmobile was a British Ford, with a 700-watt and 10-horsepower engine, staffed with three American Red Cross women who traveled throughout Great Britain, beginning on October 22, 1942.[5] After the first month of operation, the staffers requested that it would be standard for the vehicle to be supplied with records, gum, candy, cigarettes, and first aid kits to improve their services.[5]

After successful operations of the initial Clubmobile service in 1942, the American Red Cross expanded their Clubmobile services, and began using remodeled London Green Line buses in 1943. These Clubmobiles were each fitted with a kitchen consisting of a built-in doughnut machine and a primus stove for heating water for coffee. One side of the kitchen opened out for serving food and drinks, while the rear of the Clubmobile consisted of a "lounge" area with built-in benches that also doubled as sleeping bunks.

The first instance in which Clubmobile services were provided on a large scale was during the Invasion of Normandy in June 1944.[5] Around 100 GMC trucks were converted into Clubmobiles, each of which was driven and staffed by three American women. Like the original Clubmobiles, these trucks were also fitted with mini-kitchens. After the invasion, ten groups of Red Cross Clubmobile girls, with eight Clubmobiles per group, were sent to France. From this point on, the Clubmobiles traveled with the rear echelon of the Army Corps and received their orders from the Army for the duration of World War II.[5]

Volunteer recruitment process

The Red Cross required female applicants for postings overseas to be between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-five, college graduates, single, and "healthy, physically hardy, sociable and attractive."[3][6] Red Cross recruiters considered reference letters, physical examinations, and personal interviews to ensure new volunteers were a good fit for their respective roles. Despite the nature of this work being that of volunteering, application was a very competitive process, as the Red Cross only accepted one in six applicants.[3]

Duties of staffers

The foremost duty of the American Red Cross women who volunteered their service on Clubmobiles was to lift the morale of homesick GIs overseas during World War II. While their concrete responsibilities extended to providing servicemen with food and entertainment, their most significant contributions were intangible, as there was an emphasis on the character and conduct of volunteers.[3] To deliver the servicemen with the proper kind of support, volunteers received extended training and briefing: "They knew the right slang, had the right look, knew how to take and make a wisecrack, and knew how to talk about baseball and apple pie."[5] Volunteers were instructed to encourage banter, look through photos with servicemen, and listen to their stories.[3]

The women who worked the Clubmobiles were initially stationed in a town near American Army installations and traveled to a different army base daily. The Clubmobile volunteers continued their service throughout France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany until V-E Day in 1945 and provided limited service in Great Britain and Germany until 1946.[7] A variation of the Clubmobiles would also operate during the Korean War. During the Vietnam War, a similar program operated as Supplemental Recreation Overseas Program.

Gendered expectations and experiences

While some scholars position World War II as a time in which women had the opportunity to exit the domestic sphere by entering the workforce on the home front or joining war efforts on foreign land, the extent to which the nature of women's work assisted in furthering gender equality is inconclusive.[5] In the case of the American Red Cross and its Clubmobile program, it is true that unemployed women could experience life outside the domestic sphere while making meaningful contributions to their country's war efforts. However, the expectations female volunteers were expected to meet in their contributions were based on traditional notions of femininity. It is additionally valuable to consider that as a result of the application process and requirements, the demographic of Clubmobile volunteers produced was quite uniform in that these women were "by and large, white, middle to upper class and formally educated."[3] Such a distinction is why some scholars specifically argue the intricacies of the ARC to be reflective of not just "femininity" but more specifically, wealthy, white femininity. Furthermore, this truth complicates the extent to which the work Clubmobile volunteers represent large-scale gender progress but instead liberation for a select few.

Despite the implications of wartime that imposed barriers to personal hygiene and grooming, Clubmobile girls were careful to avoid "mannish" stereotypes in how they presented. Because these women ultimately stood to remind servicemen of their significant others back home, there was an unenforceable expectation that they take the time to apply lipstick, nail polish, and perfume before interacting with servicemen.[3] And while these women were symbols of traditional femininity and conventional beauty standards, they were also instructed to abstain from forming any romantic connections with the men they serviced. Perhaps it is, for this reason, Clubmobile women recall "feeling like a museum piece" for men to admire, but only from a proper distance.[3] In addition to the aesthetic expectations grounded in traditional notions of femininity, the nature of much of the work the Clubmobile volunteers did not deviate much from the kind of domestic work these women were expected to do on the home front before the war: "The work they did was traditionally defined as "women's": they cooked, cleaned up, and waited on men."[3]

While the standards Clubmobile volunteers were held to appear to have pandered to traditional ideals of femininity, centered on beauty, poise, and work that resembles the jobs typical of a homemaker, volunteers were still able to do meaningful work that temporarily granted them exposure to the public sector. It is likely for this reason scholars cite volunteer work as a meaningful outlet for the wartime woman. This sentiment is echoed in the primary sources recovered from this time in which Clubmobile women describe the nature of their work as "wonderful" and deeply rewarding.[3] In a letter home, one volunteer wrote that she felt "fortunate to be in [a] Clubmobile," adding that she "wouldn't trade [her experience] for anything else."[3] Perhaps seeing the men around them abandon all of their pre-war obligations to join their country's armed forces in conjunction with great urges from the government to "do your part" was the catalyst in women flocking to the Red Cross as a medium for wartime work. However, it was likely the connections women made in their work that propelled them to persist in their jobs, regardless of how difficult the circumstances may be or the extent to which the nature of their work mirrored domestic expectations.

References

- Apple, Carolyn. "World War II: "Donut Dollies" & the American Red Cross". Delaware Historical & Cultural Affairs.

- U.S. Senate Recognizes Red Cross Clubmobiles Accessed December 2012

- Madison, James (Fall 2007). "Wearing Lipstick to War".

- Joffe-Walt, Chana (July 13, 2012) "The Cost Of Free Doughnuts: 70 Years Of Regret" Accessed December 2012

- Ramsey, Julia A (August 6, 2011). ""Girls" in Name Only: A Study of American Red Cross Volunteers on the Frontlines of World War II". Thesis Submission: 1–143 – via Auburn University.

- "Collection of the American Red Cross Clubmobile Service, 1940-1998 (inclusive), 1943-1946 (bulk)". Hollis for Archival Discovery.

- Fay, Elma Ernst, U.S.R.C. (November 2000)"A Brief History of Red Cross Clubmobiles in WWII" Accessed December 2012

Further reading

- Korson, George (1945) At His Side: The Story of the American Red Cross Overseas in World War II. New York: Coward-McCann.

- Madison, James H. (2007) Slinging Doughnuts for the Boys: An American Woman in World War II. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Morgan, Marjorie Lee, ed. (1982) The Clubmobile - the ARC in the storm. St. Petersburg, FL: Hazlett Print. & Pub.

- Rexford, Oscar Whitelaw, ed. (1989) Battlestars & Doughnuts: World War II Clubmobile Experiences Of Mary Metcalfe Rexford. St. Louis: Patrice Press.

- Yellin, Emily (2004) Our Mothers' War: American Women at Home and at the Front During World War II. New York: Free Press.

Urea, Luis Alberto (2023) Good Night Irene New York: Little Brown and Company

External links

- The Donut Dollies, a website dedicated to the story of the American women who volunteered to go to Vietnam to help the troops forget about the war.