Amelia Opie

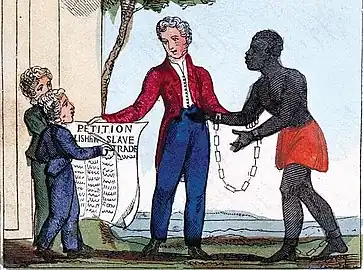

Amelia Opie (née Alderson; 12 November 1769 – 2 December 1853) was an English author who published numerous novels in the Romantic period up to 1828. A Bluestocking,[1] Opie was also a leading abolitionist in Norwich, England. Hers was the first of 187,000 names presented to the British Parliament on a petition from women to stop slavery.

Amelia Opie | |

|---|---|

A 1798 portrait of Amelia Opie by her husband, John Opie | |

| Born | Amelia Alderson 12 November 1769 Norwich, England, Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Died | 2 December 1853 (aged 84) Norwich, England, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | Gildencroft Quaker Cemetery, Norwich |

| Occupation(s) | 18th century novelist and poet |

| Spouse | John Opie (1798–1807; his death) |

Early life and influences

Amelia Alderson was born on 12 November 1769. An only child, she was the daughter of James Alderson, a physician, and Amelia Briggs of Norwich.[2] Her mother also brought her up to care for those who came from less privileged backgrounds.[2] After her mother's death on 31 December 1784, she became her father's housekeeper and hostess, remaining very close to him until his death in 1807.[3]

According to her biographer, Opie "was vivacious, attractive, interested in fine clothes, educated in genteel accomplishments, and had several admirers."(3) She was a cousin of the judge, Edward Hall Alderson, with whom she corresponded throughout her life, and was also a cousin of the artist, Henry Perronet Briggs. Alderson inherited radical principles and was an ardent admirer of John Horne Tooke. She was close to activists John Philip Kemble, Sarah Siddons, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft.[4] Along with Wollstonecraft, she was connected with the Blue Stockings Society.[5]

Career and connections

Opie spent her youth writing poetry and plays and organizing amateur theatricals.[2] She wrote The Dangers of Coquetry when she was 18 years old.

Opie completed a novel in 1801 titled Father and Daughter. Characterized as showing genuine fancy and pathos,[4] the novel is about misled virtue and family reconciliation. After it came out, Opie began to publish regularly. Her volume of Poems, published in 1802, went through six editions. Encouraged by her husband to continue writing, she published Adeline Mowbray (1804), an exploration of women's education, marriage, and the abolition of slavery. This novel in particular is noted for engaging the history of Opie's former friend Mary Wollstonecraft, whose relationship with the American Gilbert Imlay outside of marriage caused some scandal, as did her later marriage to the philosopher William Godwin. Godwin had previously argued against marriage as an institution by which women were owned as property, but when Wollstonecraft became pregnant, they married despite his prior beliefs. In the novel, Adeline becomes involved with a philosopher early on, who takes a firm stand against marriage, only to be convinced to marry a West Indian landowner against her better judgement. The novel also engages abolitionist sentiment, in the story of a mixed-race woman and her family, whom Adeline saves from poverty at some expense to herself.

More novels followed: Simple Tales (1806), Temper (1812), Tales of Real Life (1813), Valentine's Eve (1816), Tales of the Heart (1818), and Madeline (1822). The Warrior's Return and other poems was published in 1808.[6]

In 1825, Opie joined the Society of Friends, due to the influence of Joseph John Gurney and his sisters, who were long-time friends and neighbours in Norwich,[4] and despite the objections made by her recently deceased father. Opie had long known the Gurneys of Earlham Hall, Norfolk. Likewise, her future husband, artist John Opie, was "an intimate associate of the family" (having painted members of them) and met Amelia at Earlham in 1797. Amelia had been a friend of the Gurney sisters for many years. Alongside Amelia, Prince William Frederick had also been a guest at numerous balls and parties held at Earlham where the guests - both "old and young" - enjoyed "standing around his Princeship and singing - which pleased him amazingly". Harriet Martineau recalled her family's memories of the Gurney girls at this time "dressing in gay riding boots, and riding about the country to balls and gaieties of all sorts."[8][9]

In 1809, Opie published a biography on her husband John which accompanied the lectures he had given at the Royal Academy of Arts prior to his death in 1807. Her subscribers included Prince William Frederick and members of the Taylor, Gurney and Martineau families, all of whom were connected to Norwich, as was Amelia.[10]

The rest of Opie's life was spent mostly in travel and working with charities. Meanwhile she published an anti-slavery poem titled, The Black Man's Lament in 1826 and a volume of devotional poems, Lays for the Dead in 1834.[11] Opie worked with Anna Gurney to create a Ladies Anti-Slavery Society in Norwich.[12] This anti-slavery society organised a petition of 187,000 names that was presented to parliament. The first two names on the petition were Amelia Opie and Priscilla Buxton.[13] Opie went to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840 where she was one of the few women included in the commemorative painting.

Personal life

On 8 May 1798 she married artist John Opie at the Church of St Marylebone, Westminster, London. She had met Opie at a parties and balls in Norfolk including at Holkham Hall where he had come to carry out some commissions for Thomas Coke.[14] They lived at 8 Berners Street, London where Opie had moved in 1791.[15] The couple spent nine years happily married, although her husband did not share her love of society, until his death in 1807. She divided her time between London and Norwich. She was a friend of writers Walter Scott, Richard Brinsley Sheridan and Germaine de Staël. Opie's concern for the well-being of writers is evident in a letter dated 12 December, 1800 in which she wishes to hear from Susannah Taylor about the death of Mrs Sarah Martineau whom Opie had met through their mutual friend Anna Laetitia Barbauld.[16][17][18][19]

Even late in life, Opie maintained an interest and connections with writers, for instance receiving George Borrow as a guest. After a visit to Cromer, a seaside resort on the North Norfolk coast, she caught a chill and retired to her bedroom. A year later on 2 December 1853, she died at Norwich and was said to have retained her vivacity to the last. She was buried at the Gildencroft Quaker Cemetery, Norwich.

A somewhat sanitised biography of Opie, entitled A Life, by Cecilia Lucy Brightwell, was published in 1854.

Selected works

- Novels and stories

- Dangers of Coquetry (published anonymously), 1790

- The Father and Daughter, 1801

- Adeline Mowbray, 1804

- Simple Tales, 1806

- Temper; or, Domestic Scenes, 1812

- First Chapter of Accidents, 1813

- Tales of Real Life, 1813

- Valentine's Eve, 1816

- New Tales, 1818

- Tales of the Heart, 1820

- The Only Child; or, Portia Bellendon (published anonymously), 1821

- Madeline, A Tale, 1822

- Illustrations of Lying, 1824

- Tales of the Pemberton Family for Children, 1825

- The Last Voyage, 1828

- Detraction Displayed, 1828

- Miscellaneous Tales (12 Vols), 1845–1847

- Biographies

- Memoir of John Opie, 1809

- Sketch of Mrs. Roberts, 1814

- Poetry

- Maid of Corinth, 1801

- Elegy to the Memory of the Duke of Bedford, 1802

- Poems, 1802

- Lines to General Kosciusko, 1803

- Song to Stella, 1803

- The Warrior's Return and other poems, 1808

- The Black Man's Lament, 1826 (Wikisource text)

- Lays for the Dead, 1834

- Miscellaneous

- Recollections of Days in Holland, 1840

- Recollections of a Visit to Paris in 1802, 1831–1832

- Winter's Beautiful Rose, a song with words by Opie and music by Jane Bianchi dedicated to the Viscountesses Hampden[20]

References

- "Correspondence of Amelia Opie - UGA at Oxford, Fall 2022". © 2023 Roxanne Eberle. 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

She has been variously (and often simultaneously) identified as a radical Whig, conservative reactionary, flirtatious bluestocking, pious Quaker

- "Amelia Opie". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Tong, Joanne (Winter 2004). "The Return of the Prodigal Daughter: Finding the Family in Amelia Opie's Novels". Studies in the Novel. 36 (4): 465–483. JSTOR 29533647.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Opie, Amelia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 129.

- Johns, A. (2014). Bluestocking Feminism and British-German Cultural Transfer... University of Michigan. p. 173. ISBN 9780472035946. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

....Amelia Opie and Mary Wollstonecraft herself...

- I. Armstrong, J. Bristow et al., eds. Nineteenth-Century Women Poets. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1841, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG599, given by British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1880.

- Hare, A. J. C. (1897). The Gurneys of Earlham - Volume 1. Augustus John Cuthbert Hare. p. 72-95. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

To the Earlham sisters , Mrs. Opie's musical talents gave her an especial charm ...she [Amelia] had first met at Earlham in 1797 [her furture husband John Opie]... She would practise for hours with Rachel Gurney and her younger sisters , whom Miss Martineau describes as- " A set of dashing young people , dressing ..."...[page 72] January 12, 1798...the Prince has been here again...[December 29, 1798]...Everybody looked cheerful, and we eleven stood round His Princeship , and sang the Chapter of Kings , which pleased him amazingly ....[page 73] After the Prince was gone, we had a dance...all joined, single and married, old and young...[page 94] December 29 1798 - Yesterday we had a great deal of company - Amelia Alderson,..the Prince...

- Rogers, J. (1878). Opie And His Works. Colnaghi. p. 211. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

Painting named "A Fortune Teller" - Opie painted the Gurney family [late 18th century]

- Opie, Mrs (Amelia) (1809). A Memoir By Mrs Opie. Longman etc - Paternoster Row, London. p. iv. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Armstrong, Bristow et al.

- Women's Anti-Slavery Associations, Spartacus, Retrieved 30 July 2015

- Genius of Universal Emancipation. B. Lundy. 1833. p. 174.

- Earland, 1911, p. 124.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 129.

- Opie, Amelia (12 December 1800). "Amelia Opie's letters to Susannah Taylor". Retrieved 4 June 2023.

It is strange I should have written so far, without naming the subject on which I wanted particularly to talk to you — I suppose you attended poor Mrs. Martineau's deathbed and I feel a great curiosity to know some particulars of her last moments — were her children with her? and had she her senses to the last ?

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Di Giacomo, P (2016). ""There were banquets and parties every day": the importance of British female circles for the Serbian Enlightenment - A study of Dositej Obradović, Serbia's First Minister of Education (1739/42-1811)" (PDF). Књиженство (Knjiženstvo). Università degli Studi “G. d’Annunzio”. 6: 13. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

Dositej Obradović...The Unitarian Sarah Meadows Martineau (ca 1725-1800), who sent her children to Anna Laetitia Barbauld's school in Palgrave, also lived in Norwich. Martineau was a relative of the Taylors, and thanks to her Anna Laetitia Barbauld was able to meet Susannah Taylor...important of these was The Blue Stockings Society, founded in the early...The women that he met within the Scottish community and among the Unitarians such as Mrs Livie and her sister Mrs Taylor, transferred to Obradović the knowledge they had gained from frequenting the feminist circles of Elizabeth Carter, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Elizabeth Montagu, Elizabeth Vessey, Margaret Cavendish Bentinck Sarah Fielding, Hannah More, Clara Reeve, Amelia Opie, Sarah Meadows Martineau. Their knowledge of the then current literary and cultural scene enabled Obradović to supply the works that he took from England and translated and adapted for the Serbian nation.

- "ORLANDO Women's Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present - Susannah Taylor". Cambridge University Press. 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

Susannah Taylor - Friends, Associates Anna Letitia Barbauld - Pupils who acknowledged her [Barbauld's] influence included (Judge) Thomas Denman, who later drafted the 1832 Reform Act. Friends from this period of her [Barbauld's] life included Susannah Taylor (mother of the translator and editor Sarah Austin)...

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - McCarthy, W. (2008). Anna Letitia Barbauld: Voice of the Enlightenment. Johns Hopkins University. p. 394. ISBN 9780801890161. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

Amelia Opie was one who fell: I was lamenting to Mrs. Barbauld ... that Miss M. did not seem to have any taste for reading. 'So much the better,' was [Barbauld's] answer [to Opie], 'I do not think such a taste desirable. Reading is an indolent way of...

- "Winter's beautiful rose / the words by Mrs. Opie ; the music composed... by Mrs. Bianchi Lacy". HathiTrust. hdl:2027/mdp.39015080964995. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

Further reading

- Brightwell, Cecilia Lucy (1855). Memoir of Amelia Opie. London: The Religious Tract Society; 244 pages — abridgment of Memorials

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Eberle, Roxanne (1994). "Amelia Opie's 'Adeline Mowbray': Diverting the Libertine Gaze; Or, The Vindication of a Fallen Woman". Studies in the Novel. 26 (2): 121–52.

- Howard, Carol (1998). "'The Story of the Pineapple': Sentimental Abolitionism and Moral Motherhood in Amelia Opie's Adeline Mowbray". Studies in the Novel. 30: 355–76.

- Susan K. Howard, "Amelia Opie", British Romantic Novelists, 1789–1832. Ed. Bradford K. Mudge. Detroit: Gale Research, 1992.

- Kelly, Gary (1980). "Discharging Debts: The Moral Economy of Amelia Opie's Fiction". The Wordsworth Circle. 11 (4): 198–203. doi:10.1086/TWC24040631. S2CID 165211713.

- Gary Kelly, English Fiction of the Romantic Period, 1789–1830. London: Longman, 1989.

- Shelley King and John B. Pierce, "Introduction", The Father and Daughter with Dangers of Coquetry. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2003.

- James R. Simmons, Jr, "Amelia Opie". British Short-Fiction Writers, 1800–1880, ed. John R. Greenfield. Detroit: Gale Research, 1996.

- Dale Spender, Mothers of the Novel: 100 Good Women Writers Before Jane Austen. London: Pandora, 1986.

- William St. Clair, The Godwins and Shelleys: The Biography of a Family. London: Faber and Faber, 1989.

- Kunitz, Stanley (1936). British Authors of the Nineteenth Century. New York: H. W. Wilson Co.

- Susan Staves, "British Seduced Maidens", Eighteenth-Century Studies 12 (1980–81): 109–134.

- Eleanor Ty, Empowering the Feminine: The Narratives of Mary Robinson, Jane West, and Amelia Opie, 1796–1812. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

External links

- Amelia Opie at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by Amelia Opie at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Amelia Opie at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Amelia Opie at Internet Archive

- Works by Amelia Opie at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Amelia Opie and Norwich

- "Archival material relating to Amelia Opie". UK National Archives.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 42. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 226–230.

- Cecilia Lucy Brightwell, Memorials of the life of Amelia Opie, London: Longman, Brown, & Co., 1854

- The Amelia Alderson Opie Archive Archived 3 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Amelia Opie at Poeticous