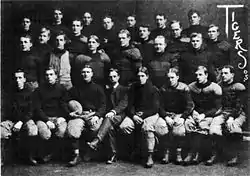

Massillon Tigers

The Massillon Tigers were an early professional football team from Massillon, Ohio. Playing in the "Ohio League", the team was a rival to the pre-National Football League version of the Canton Bulldogs. The Tigers won Ohio League championships in 1903, 1904, 1905, and 1906, then merged to become "All-Massillons" to win another title in 1907. The team returned as the Tigers in 1915 but, with the reemergence of the Bulldogs, only won one more Ohio League title. Pro football was popularized in Ohio when the amateur Massillon Tigers hired four Pittsburgh pros to play in the season-ending game against Akron. At the same time, pro football declined in the Pittsburgh area, and the emphasis on the pro game moved west from Pennsylvania to Ohio.

| |

| Founded | 1903 |

|---|---|

| Folded | 1923 |

| Based in | Massillon, Ohio, US |

| League | Ohio League (1903–1906, 1915–1919) |

| Team history | Massillon Tigers (1903–1906, 1915–1923) "All-Massillons" (1907) |

| Team colors | Black, orange |

| Head coaches | E. J. Stewart (1903–1905) Sherburn Wightman (1906–1907) Stan Cofall (1915–1916) Charles Brickley (1917) Bob Nash (1917–1919) |

| General managers | Jack Goodrich (1903–1904) J.J. Wise (1905–1906) E. J. Stewart (1906) Sherburn Wightman (1907) Stan Cofall (1915–1916) Charles Brickley (1917) Bob Nash (1917–1919) |

| Owner(s) | Massillon Tigers |

| Ohio League Championship wins | (6) 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1907, 1915 |

| Undefeated seasons | (3) (1904, 1905, 1907) |

| Mascot(s) | Obie |

The team opted not to join the APFA (later renamed the NFL) in 1920; it remained an independent club through 1923, when the Tigers folded. During their time as an independent, the Tigers never played against any team in the NFL, even though several other independent teams did. The Massillon Tigers team name was transferred to Massillon Washington High School, which still uses it.

History

Origins

The Massillon area had fielded several amateur football teams featuring only local players since the early 1890s. However while some had performed well, the others were more likely to be defeated when they played their cross-county arch-rival, Canton. Therefore, a group of 35 area businessmen met on September 3, 1903 at the Hotel Sailor in Massillon to form the area's first professional football team. Jack Goodrich, who expected to play halfback for the new team, was named manager. Meanwhile, Ed J. Stewart, a young and ambitious editor of the city newspaper The Evening Independent, was named as the team's first coach. Stewart had playing experience while attending Western Reserve College and Mount Union College. Apart from being the team's coach, he later appointed himself as the team's quarterback.

Name origin

J.J. Wise, who was the Massillon Clerk of City Council, led a committee to secure the necessary funds for a new football and jerseys that were nearly the same color. The local venders only had a sufficient quantity of one jersey style to outfit an entire team. Those jerseys imitated the orange and black striped attire of the Princeton Tigers, so the new Massillon team was christened the "Tigers."

Inaugural season

When the Tigers began play in 1903, several of the expected starters hadn't touched a football in eight or more years. According to locals belief, Baldy Wittman, 32-year-old proprietor of a local cigar store and a spare-time police officer, had never played the game at all. Charles "Cy" Rigler, who later became a famous major league baseball umpire started at tackle. Wittman opened at an end and was elected the team captain. Meanwhile, Stewart lined himself up at quarterback. The Tigers first game against Wooster College ended in a 6-0 defeat. A biased official was the excuse for the loss.[1] The Tigers followed their first ever game with a 16-0 victory over Stewart's alma mater, Mount Union College, a 6-0 victory over the Akron Imperials, and a 38-0 over the Akron Blues. After a 34-0 victory over the Dennison Panhandles, the Tigers prepared for their cross-county rivals, a sandlot team from Canton. Betting on the games, during the early 1900s was common. It is believed that over $1000 was risked on the game's outcome. The Tigers held on to a 16-0 score to win the first game between the two clubs.

After the Canton-Massillon game, the Tigers began to look at winning the mythical "Ohio League" championship. On Thanksgiving Day 1903, the Tigers avenged their only loss of the season against Wooster College with a 34-0 score. This outcome gave legitimacy to the belief that the Tigers were robbed by a corrupt official in their inaugural game.[1] On December 5, an agreement was signed by Massillon and the Akron East Ends to play. The contract called for a 75-25 split of the gate, with the winner taking the 75% of the gate. However Massillon soon found itself in a troubling situation due to injuries to several of their star players. The team's management decided to replace the injured players with "ringers". Several pro football players from the Pittsburgh area soon traveled to Ohio to play for Massillon. Among them was Bob Shiring and Harry McChesney, who played in 1902 with the Pittsburgh Stars of the first National Football League. These player developments did not sit well with the Akron media, most notably the Akron Beacon-Journal. Massillon would go on to win the championship game 12-0, however the Akron Beacon-Journal later stated that most of Massillon's 75% gate money went to the Pittsburgh ringers. Plans were soon in the mix for spending $1,000 on a 1904 Tigers team.[1]

1904

In 1904 the Tigers repeated as Ohio League champions. It was during this time that at least seven teams in Ohio began hiring players for games. Most of these "ringers" were from Pittsburgh. Many players were hired on a per game basis and were never signed to any written contract. Ted Nesser, of the infamous Nesser Brothers, played for the Shelby Blues until he was hired to play one game for the Tigers. For the next two season he remained in the Tigers lineup.[2] However, after the Tigers began the 1904 season, many Massillonians were bored with the ease of the Tigers' wins, even at this early stage. That season the Tigers defeated a club from Marion 148-0. Also keep in mind that a touchdown counted only five points until 1912. However under the rules of the time, the team that scored turned around and received the next kickoff (traditionally, onside kicks were far more commonplace—and easier—at this time, but Marion chose not to use them for reasons unexplained). During the game a Massillon end named Walt Roepke ran a punt back for a touchdown. Marion never got another chance to handle the ball, as Massillon took kickoff after kickoff and moved down the field to touchdown after touchdown.

The Tigers defeated the Akron East Ends again (now renamed the Akron Athletic Club) 6-5 after Akron's Joe Fogg missed an extra point kick on the last play of the game.[2]

Bulldogs-Tigers rivalry: 1905-1906

By 1905 the Tigers were considered one of the top three teams in the country, along with the Latrobe Athletic Association and the Canton Bulldogs. Both teams were constantly fighting for the best players in football. In fact the Bulldogs, or Canton Athletic Club as it was called at the time, formed their football team in 1905 with sole objective of beating the Tigers, who had won every Ohio League championship since 1903.[3][4]

1905 championship

Both teams spent lavish amounts of money to bring in ringers from out of town. The teams first played each other twice in 1905, with Massillon winning the first game 14-4. The second game saw a 10-0 Massillon win, however the win drew protests from Canton coach Blondy Wallace, who argued against a 10-ounce ball used by Massillon during the game, instead of the regular 16-ounce ball. The 10-ounce ball was provided to the Tigers by their owner, a Massillon newspaper editor. The protest fell on deaf ears, and Massillon was named the 1905 Ohio League champions.[5]

1906 financial charges

In the off-season prior to the 1906 season, a news story in The Plain Dealer alleged that the Canton Athletic Club was financially broke and could not pay its players for that final game. The club denied the allegation and insisted that every dollar promised had indeed been delivered. Many Canton followers believed the story had originated in Massillon as a trick to discredit their team and make it tougher for Canton to recruit players for 1906. Massillon coach, Ed Stewart, who had newspaper connections was believed by Canton to have planted the story. However, while Canton was in fact losing money in 1905, a group of area businessmen shouldered the losses.

In a counter-charge, Canton insisted that the Tigers were also deeply in debt. However, a statement by the Tigers showed $16,037.90 in receipts and only $16,015.65 in expenditures. The only problem with Massillon's figures was that they only listed salaries, including railroad fare, at $6,740.95, which means the players were getting only about $50 per game. However, it is believed, like with Canton, that Massillon's area boosters picked up whatever losses the Tigers incurred during 1905.[3][5]

Recruitment

For the 1906 season, Canton coach Wallace signed the entire backfield of the Tigers to the Canton team.[6] While in Massillon, Ed Stewart was promoted from head coach to manager. Sherburn Wightman, who played under Amos Alonzo Stagg at the University of Chicago, was then named the team's new coach.[5]

1906 scandal

In 1906, the Bulldogs and Tigers were involved in a game-rigging scandal that effectively killed both teams. It was the first major scandal in professional football, and the first known case of professional gamblers attempting to fix a professional sport. The Massillon Independent newspaper alleged that the Bulldogs coach, Blondy Wallace, and Tigers end, Walter East, had conspired to fix a two-game series between the two clubs. The conspiracy called for Canton to win the first game and Massillon to win the second, forcing a third game, which would have the largest gate. That game would be played legitimately, with the 1906 Ohio League championship at stake.

Canton denied the charges, maintaining that Massillon only wanted to damage the club's reputation. Although Massillon could not prove that Canton had indeed thrown the second game, the scandal tarnished the Bulldog and Tiger names and helped ruin professional football in Ohio until the mid 1910s. To this day the details of the scandal consist only of charges and counter-charges.[7]

"All-Massillons"

A reorganized "All-Massillons" played in 1907, after which professional football in Massillon effectively stopped. The team was made up of many of the former Tigers players and was managed by Sherburn Wightman. The team defeated the Columbus Panhandles, with the Nesser Brothers in the line-up, 13-4, and celebrated its fifth consecutive state championship. Because of the game's importance, Massillon brought in two ringers, Peggy Parratt and Bob Shiring.[8]

In 1911 a Canton-Massillon game was hyped beforehand as a return to 1905-06. However, after seeing the 57-0 Canton victory, it became apparent that this Massillon team bore little resemblance to the Tiger teams of the past, although the lineup did include Tiger greats Baldy Wittmann and Frank Bast.[9]

Dispute with Cusack

During the summer of 1914, members of the Massillon Chamber of Commerce asked Jack Cusack, the manager of the re-organized Canton Bulldogs, to attend a secret meeting to discuss a proposed new Massillon Tigers football team. Cusack believed that a game against a strong Massillon team and a restart of the historic Canton-Massillon rivalry was bound to bring in fans to Canton. However, in order to get the team fielded, Massillon planned to raid the Akron Indians roster of its key players. Because of this, Cusack refused to help Massillon restart their club. In 1914, an unwritten agreement existed among Ohio League managers that refrained them from raiding other teams. Also a raid of players would start a bidding war, raise players' salaries for all teams, and destroy the fragile profit margin already established. Cusack refused to provide a Canton-Massillon game if players from the Indians were raided. Plans for a new "Tigers" were put on hold until 1915.

1915

The Tigers returned to the Ohio League in 1915. They were backed by local businessmen, Jack Donahue and Jack Whalen. Massillon did end up raiding the Indians team of their top players. In turn Cusack took in the Akron players, and raided the Youngstown Patricians, hoping to improve his team. Massillon hired new ringers for a new bidding war with Canton, however Cusack signed the legendary Jim Thorpe to his squad. The Tigers ended their 1915 season with a share of the 1915 championship with Canton. Both teams finished the season 5-2-0. One anonymous Massillon official revealed it had taken between $1,500 and $2,000 to bring in the Tigers lineup that opposed Canton in the final game, which included three players from Muhlenberg College, who had their college eligibility stripped when they were discovered.[10] This would be Massillon's last "Ohio League" title, and a disputed one at that—the very Patricians squad that the Tigers had raided earlier in the season had racked up an even more impressive 9-0-1 record against lesser talent, including a win against the Washington Vigilants, one of the East Coast's top professional teams, leading many observers to give Youngstown the title instead.[11]

1916

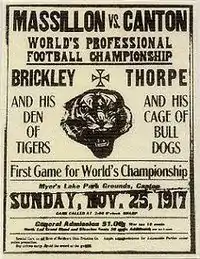

The Tigers rebirth, saw the team incorporate many of the top players of the era. For example, Knute Rockne, Charles Brickley, Gus Dorais, Bob Nash, Stan Cofall, and, future Hall of Famer, Greasy Neale. The 1916 season saw the Tigers end up in second place of the "Ohio League" standings behind the Canton Bulldogs. However, despite record crowds for two Bulldog-Tigers match-ups, Massillon lost money on the season, while Canton barely made a profit. Most of the Midwestern major teams were running into debt. Since every player knew Jim Thorpe was being paid $250 a game, many players of considerably less talent were holding out for $100 or $125 a game. Team managers had to produce stars to draw crowds, but the crowds could never be big enough to pay for the stars. Teams desperately needed something like the old "Ohio League" sub-rosa agreement where the managers agreed to not raid other team rosters. Only that sort of agreement could hold salaries at a responsible level.[12]

1917

In 1917, Bob Nash promised an "Ohio League" championship to the fans in Massillon. In doing so he put together an offensive line that included Charlie Copley at tackle and Al Wesbecher at center. However, after storming out to a 4-0 start, the Tigers were defeated by Stan Cofall and the Youngstown Patricians 14-6. However, later that season Cofall and Bob Peck decided to play for Massillon which prematurely ended the Pats 1917 campaign. However, despite their winning seasons and star talent, Massillon was still losing money. One reason for the disparity is that Massillon was smaller than Canton, meaning it had a smaller fan base to support its football team. The Tigers had highly devoted following, however they weren't enough of them. Also the city lacked a decent ballpark. as a result many of the Tigers' biggest home games were undersold. The only way to make the Tigers profitable was to use Peggy Parratt's old Akron scheme of bringing in just enough high-priced stars to win. Even then, the Tigers would have probably operated at a loss, but one small enough that it could be made up for by the team's backers. However Massillon did upset the Bulldogs in their second game of the season series 6-0, behind two field goals kicked by Cofall. But despite the upset, Canton was regarded as the U.S. champion; Massillon couldn't make a serious claim. The Tigers had lost their first game with the Bulldogs by a larger margin and dropped two other games to lesser opponents. It had not been a good season for Massillon. They lost three games on the field, and their backers dropped $4,700 at the gate. After the season, a "Cleveland critic" chose an all-pro team from among the four major northeastern Ohio teams. The Massillon players on the all-pro listing were Bob Nash, Bob Peck, Pike Johnson, Charley Copley, and Stan Cofall.[13] One of the teams Massillon would play (and defeat soundly) in 1917 was the Buffalo All-Stars, who would later join the NFL as the Buffalo All-Americans in 1917.

The team suspended operations in 1918 due to a flu pandemic and the Great War, but returned in 1919.

1919

Many of the top teams of the "Ohio League" returned to action in 1919. At a meeting on July 14, 1919, the managers held a "get-together" at Canton's Courtland Hotel. The managers decided on a pay scale for officials and agreed to refrain from stealing each other's players for the upcoming season. However, the big surprise came when Massillon backer Jack Donahue refused to go along with a proposal to limit salaries. Massillon had trouble with the increasing cost of players and would profit more by a salary cap than anyone else. Donahue insisted, "If a manager wants to pay $10,000 for a player, that's his business."

The Tigers were set to begin their 1919 season in New York City against the New York Brickley Giants, organized by the same Charles Brickley that had played for Massillon in 1917. However, due to a dispute over the application of New York's blue laws, that prohibited playing football on Sundays, Brickley's Giants were forced to fold. (The Giants team would however regroup and play in the National Football League in 1921 and as an independent until 1923; a second, unrelated New York Giants would join the league for 1925 and this is the New York Giants team that is in the NFL today.) The Tigers did play well in 1919, however once again they came in second to Canton in the "Ohio League" standings. The team's backers then decided to fold the team after losing over $5,000 during the season. Stan Cofall also abandoned the Tigers after the season. He and many of the now former-Tigers players left to play for the Cleveland Tigers.[14][15]

Attempts to restart the Tigers

On August 20, 1920, during the first meeting aimed at establishing the American Professional Football Association (renamed the National Football League in 1922), there was hope that F.J. Griffiths, of the Massillon steel industry, would resurrect the franchise, but the meeting passed with no word from Griffiths. During late August and early September of that same year, Ralph Hay and Jim Thorpe tried without success to find a backer for a new Massillon team. While the Tigers consistently lost money for themselves, they were always a good draw for others. In fact it was a strong rivalry with Massillion that helped lead Jim Thorpe to Canton. Cupid Black, an All-America guard from Yale, was also rumored to restart the Tigers franchise, however he later turned down the offer.[14]

Vernon Maginnis issue

On September 17, 1920, at Ralph Hay's Hupmobile dealership in Canton, the charter members of the future NFL formally established the new league. During that meeting, the first order of business was to decide the future of the Massillon franchise. It was then that the managers were confronted by Vernon Maginnis, the manager of the unsuccessful Akron Indians in 1919, who wanted to field a traveling team and call it the "Massillon Tigers". Hay and the other managers turned down the offer because they didn't feel the franchise would pan out and because nobody wanted to see the proud Massillon Tigers name demeaned and made a road attraction. The current Akron owners, now renamed the Pros, Art Ranney and Frank Nied were also associated with Maginnis during his ownership of the team in 1919, and had many problems with him during that season.[14]

Maginnis' representative was not admitted to the meeting, however the Massillon Tigers were counted as present at the charter meeting of the NFL. Hay, who'd tried to get a real Massillon team restarted, considered himself as their spokesman. Once the meeting started, he stood up and announced that Massillon was withdrawing from professional football for the season of 1920. And to resure that Maginnis wouldn't try to reestablish a Massillon "franchise", Hay told the American Professional Football Association managers: "Do not schedule any `other' Massillon team".[14]

Charter NFL member?

The 10 teams represented at the September 17 meeting are considered charter members of the AFPA, and, by extension, of the National Football league. Massillon is usually counted on a technicality: the team, under Hay, were there, they just never played in the new league.[14]

References

- Carroll, Bob. "Ohio Tiger Trap" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-26.

- PFRA Research. "Ohio Pounce Again" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-26.

-

- Peterson, Robert W. (1997). Pigskin: The Early Years of Pro Football. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511913-4.

- Lahmen, Sean (October 10, 2008). "Canton vs. Masillon, 1906". In Lahmen's Terms. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- "Blondy Wallace and the Biggest Football Scandal Ever" (PDF). PFRA Annual. Professional Football Researchers Association. 5: 1–16. 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-18.

- Ross, Charles K. (1999). Outside the Lines: African Americans and the Integration of the National Football League. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-7496-2.

- "Blondy Wallace and the Biggest Football Scandal Ever" (PDF). PFRA Annual. Professional Football Researchers Association. 5: 1–16. 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-18.

- PFRA Research. "Glamourless Gridirons: 1907-09" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26.

- PFRA Research. "Parratt Wins Again" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26.

- "College Gridders Are Declared Ineligible". The Mansfield Shield. November 18, 1915.

- PFRA Research. "Thrope Arrives" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-11.

- PFRA Research. "The Super Bulldogs 1916" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-06.

- PFRA Research. "Canton Wins Again 1917" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-17.

- PFRA Research. "Associating in Obscurity 1920" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-18.

- PFRA Research. "Forward into Invisibility 1920" (PDF). Coffin Corner. Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-18.