Aljamiado

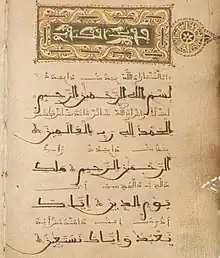

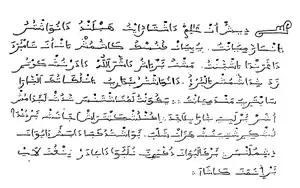

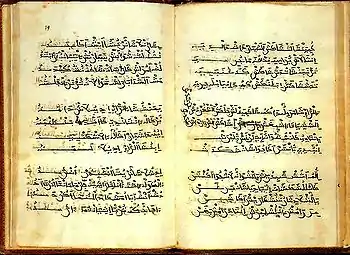

Aljamiado (Spanish: [alxaˈmjaðo]; Portuguese: [alʒɐmiˈaðu]; Arabic: عَجَمِيَة trans. ʿajamiyah [ʕaʒaˈmij.ja] Persian: الجامیادو trans. ʿajemiya or Aljamía texts are manuscripts that use the Arabic script for transcribing European languages, especially Romance languages such as Mozarabic, Aragonese, Portuguese, Spanish or Ladino.

According to Anwar G. Chejne, Aljamiado or Aljamía is "a corruption of the Arabic word ʿajamiyah (in this case it means foreign language) and, generally, the Arabic expression ʿajam and its derivative ʿajamiyah are applicable to peoples whose ancestry is not of Arabian origin".[3]

History

The systematic writing of Romance-language texts in Arabic scripts appears to have begun in the fifteenth century, and the overwhelming majority of such texts that can be dated belong to the sixteenth century.[4] A key aljamiado text is the compilation Suma de los principales mandamientos y devediamentos de nuestra santa ley y sunna by the mufti of Segovia, of 1462.[5]

It was used by some people in some areas of Al-Andalus as an everyday communication vehicle, while Arabic was reserved as the language of science, high culture, and religion.

In later times, Moriscos were banned from using Arabic as a religious language, and wrote in Spanish on Islamic subjects. Examples are the Coplas del alhichante de Puey Monzón, narrating a Hajj,[6] or the Poema de Yuçuf on the Biblical Joseph (written in Aragonese).[7]

Aljamiado played a very important role [8] in preserving Islam and the Arabic language in the life of the Moriscos of Castile and Aragon; Valencian and Granadan Moriscos spoke and wrote in Andalusi Arabic. After the fall of the last Muslim kingdom on the Iberian peninsula, the Moriscos (Muslims in parts of what was once Al-Andalus) were forced to convert to Christianity or leave the peninsula. They were forced to adopt Christian customs and traditions and to attend church services on Sundays. Nevertheless, some of the Moriscos kept their Islamic belief and traditions secretly, and this included the usage of Aljamiado.

In 1567, Philip II of Spain issued a royal decree in Spain, which forced Moriscos to abandon using Arabic on all occasions, formal and informal, speaking and writing. Using Arabic in any sense of the word would be regarded as a crime. They were given three years to learn the language of the Christian Spanish, after which they would have to get rid of all Arabic written material. Moriscos of Castile and Aragon translated all prayers and the Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) into Aljamiado transcriptions of the Spanish language, while keeping all Qur'anic verses in the original Arabic. Aljamiado scrolls were circulated amongst the Moriscos. Historians came to know about Aljamiado literature only in the early nineteenth century. Some of the Aljamiado scrolls are kept in the Spanish National Library in Madrid.

During the Arab conquest of Persia, the term became a pejorative.[9]

Transcription

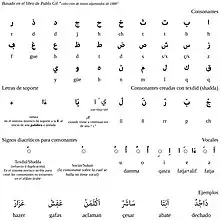

Vowels

The long vowels in Arabic were used to write the stressed vowels in Romance languages and the short vowels were used for unstressed vowels.

| Stressed Vowels | Trascription |

|---|---|

| ﺍ | á |

| ﻭ | ú |

| ﻱ | í |

| Unstressed Vowels | Trascription |

|---|---|

| ـَ | a |

| ـُ | u |

| ـِ | i |

In turn, these three vowels were written as three different letters when they occupied the final position.

| Unstressed Vowels | Transcription |

|---|---|

| ة | -a |

| ه | -u |

| ى | -i |

Since the vowels /e/ and /o/ did not exist in Arabic, they were created as a combination of short and long vowels without differentiating between unstressed and stressed vowels.

| Vowels | Transcription |

|---|---|

| ـَا | e |

| ـُو | o |

Some texts simplified this system by writing all vowels as short vowels, without differentiating between unstressed, stressed, and final vowels.

Consonants

Muslim writers solved the absence of certain phonemes in Arabic by modifying certain letters using the diacritical mark for gemination.

| Letter | Transcription |

|---|---|

| بّ | p |

| جّ | č |

| شّ | š |

Sometimes the same letter was used without marking it with a shadda, which has caused ambiguities in some cases. The sound /p/ was represented on rare occasions as ف (f) and فّ (double f).

Some letters simply adopted another value or were solved through digraphs.

| Letter | Transcription |

|---|---|

| ج | ʒ |

| غ | g |

| س | ts |

| ص | ts |

| لْي | ʎ |

| نْي | ɲ |

The phoneme /β/ was typically represented by the letter ب (b), though in some instances it was represented by the letter ف (f). The plosive consonants were required to be aspirated;[10] however, this aspect was lost in weaker positions such as the initial position of a word or an intervocalic position. In Aljamiado texts, the letter ط was utilized to represent the phoneme /t/ in initial and intervocalic positions where it was unaspirated, while the letter ت was utilized in postconsonantal positions to indicate the aspirated form of the phoneme. Similarly, the letter ﻕ was used to represent the phoneme /k/ in initial and intervocalic positions where it was unaspirated, and the letter ﻙ was used in postconsonantal positions to indicate the aspirated form. However, according to the glossary of Abuljair, the aspiration of plosive consonants never ceased to occur in any position.

Other uses

The practice of Jews writing Romance languages such as Spanish, Aragonese or Catalan in the Hebrew script is also referred to as aljamiado.[11]

The word aljamiado is sometimes used for other non-Semitic language written in Arabic letters:

- Bosnian and Albanian texts written in Arabic script during the Ottoman period have been referred to as aljamiado. However, many linguists prefer to limit the term to Romance languages, instead using Arebica to refer to the use of Arabic script for Slavic languages like Bosnian.

- The word Aljamiado is also used to refer to Greek written in the Arabic/Ottoman alphabet.[12]

See also

- Ajami script – Arabic script used for various African languages

- Arabic Afrikaans – Variant of Arabic script used to write the Afrikaans language

- Arebica – Serbo-Croatian variant of the Arabic script

- Belarusian Arabic alphabet – Arabic-based alphabet for Belarusian

- Elifbaja shqip – Writing system for the Albanian language during the Ottoman Empire

- Jawi (script) – Arabic alphabet used in Southeast Asia

- Judeo-Spanish – Language derived from Medieval Spanish spoken by Sephardic Jews

- Karamanli Turkish – Greek-written Turkish dialect of the Karamanlides

- Kharja – final refrain of a muwashshah

- Mozarabic language – Medieval Romance dialects of Al-Andalus

- Xiaoerjing – Practice of writing Sinitic languages in the Perso-Arabic script

References

- Martínez-de-Castilla-Muñoz, Nuria (2014-12-30). "The Copyists and their Texts. The Morisco Translations of the Qur'ān in the Tomás Navarro Tomás Library (CSIC, Madrid)". Al-Qanṭara. 35 (2): 493–525. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2014.017. ISSN 1988-2955.

- The passage is an invitation directed to the Spanish Moriscos or Crypto-Muslims so that they continue fulfilling the Islamic prescriptions in spite of the legal prohibitions and so that they disguise and they are protected showing public adhesion the Christian faith.

- Chejne, A.G. (1993): Historia de España musulmana. Editorial Cátedra. Madrid, Spain. Published originally as: Chejne, A.G. (1974): Muslim Spain: Its History and Culture. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, USA

- L.P. Harvey. "The Moriscos and the Hajj" Bulletin of the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies, 14.1 (1987:11-24) p. 15.

- "Summa of the principal commandments and prohibitions of our holy law and sunna". (Harvey 1987.)

- Gerard Albert Wiegers, Islamic Literature in Spanish and Aljamiado 1994, p. 226.

- MENÉNDEZ PIDAL, Ramón, Poema de Yuçuf: Materiales para su estudio, Granada, Universidad de Granada, (1952) p. 62-63

- Harvey, L. P. (1990). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-226-31960-1. OCLC 20991790.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Frye, Richard Nelson; Zarrinkoub, Abdolhosein (1975). "Section on The Arab Conquest of Iran". Cambridge History of Iran. London. 4: 46.

- Torreblanca, Máximo (1986). "Las oclusivas sordas hispanolatinas: El testimonio árabe". Anuario de Letras. Lingüística y Filología. 24: 5–26.

- "Unveiling Judeo-Spanish Texts: A Hebrew Aljamiado Workshop".

- Balim-Harding, Çigdem; Imber, Colin, eds. (2010-11-20). "The Balance of Truth: Essays in Honour of Professor Geoffrey Lewis". The Balance of Truth. Gorgias Press. doi:10.31826/9781463231576. ISBN 978-1-4632-3157-6.

Further reading

- Los Siete Alhaicales y otras plegarias de mudéjares y moriscos by Xavier Casassas Canals published by Almuzara, Sevilla (Spain), 2007. (in Spanish)