Al-Rasheed Street

Al-Rasheed Street or Al-Rashid Street (Arabic: شارع الرشيد, romanized: Shari' al-Rashīd) is one of the main streets in downtown Baghdad, Iraq. Named after Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid, it is one of the most significant landmarks of the city due to its political, urban, cultural, and artistic history.[1] Located near al-Maidan Square, the Street is considered an important urban heritage site of Baghdad and bears witness to what Iraq has gone through in terms of political events, security unrest, and popular protests that Iraq saw over the course of more than a century. The street includes many ancient landmarks such as Haydar-Khana Mosque. In recent years, the street started to suffer severely from neglect and destruction but efforts and campaigns to rehabilitate the street were outlined.[2]

| |

| Native name | Arabic: شارع الرشيد |

|---|---|

| Former name(s) | Halil Kut Avanue C. Hindenburg Street Al-Nasr Street |

| Part of | Old Baghdad |

| Location | Baghdad, Iraq |

| Other | |

| Known for |

|

| Status | Active |

Historically, the street has gone by many names. Al-Rasheed Street is considered a symbol of transformation of Baghdad due to the many changes the city has seen through the last century. The street has been compared to various notable streets around the world such as the Champs-Élysées in Paris, the Muhammad Ali Street in Cairo, and the Hamra Street in Beirut due to their artistic, historic and influential significance.[3] The street has also been suggested to be enlisted on UNESCO's World Heritage Site due to its history and significance and many efforts were done to get it enlisted.[4]

Historical background

Early years (1900s-1917)

The street's origin dates back to the Ottomans who ruled Iraq from 1534 to 1918. During that time, the only known public street in Baghdad was al-Naher Street (Shari' al-Naher). The street was established by Halil Kut the ruler of Baghdad and the commander of the Ottoman army, and it was named after him "Halil Kut Avenue C." Due to the lack of money, Halil started to demolish property that belonged to the poorer classes, and the disabled which caused clashes between the scholars of the area and the Ottomans. Although the Street was expanded for it to facilitate the movement of the Ottoman army and its vehicles, it eventually developed its own identity and became an important street due to its political, urban, cultural, and artistic evidence. Among these is the ancient Chakmakchi Company for Recording Musical and Lyric Records, located on the Eastern side of the street. Many prominent theaters, cinemas, and nightclubs also showed up.[1][5]

The street was opened in 1914 by the Ottoman administration as a modern avenue for transportation and to expand trade. Due to the fact that the narrow road networks that were common in Iraq at the time didn't suit carriages or transportation, the street was wider with sidewalks that included arcades that acted as shading for pedestrians. The street would later be expanded along the older parts of Baghdad and was always kept near to the Tigris River.[6] Due to the fact that it was the first proper modern street in Baghdad, the street wasn't paved into a straight line but rather took a curve. It was also comparably narrow compared to later street avanues in Baghdad.

During the British colonialism of Iraq, Haydar-Khana Mosque, a mosque located on the street, started to become one of the brewing aspects of the Iraqi Revolt due to how frequent the notables and personalities of the city gathered in opposition to the British. British troops reportedly stormed the mosque in an attempt to arrest the revolutionaries. Even after the independence of the Kingdom of Iraq, the area stayed as a hot spot for revolutionary gatherings.[7][8]

In 1917, al-Rasheed Street was the first street to be electrically illuminated in the city.[9]

Developing its identity (1920s-1980s)

The street names were changed several times such as "Hindenburg Street" which was a name used by the British and then later "al-Nasr Street". It was until the name settled on its current name in 1936, which was launched by the Iraqi linguist and historian Mustafa Jawad after Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid.[1][10] During the Royal Era and even during World War II, the street flourished as schools supported by King Faisal I started to materialize. Even for decades, coffeehouses became schools of thought and culture that people frequented and customers gathered in them to drink Arabic coffee and Iraqi tea brought from the fields of Sri Lanka. Popular Cafes for the educated class and pioneers of thought also started to be built and scattered throughout the street. Libraries were also to be found since the gate to al-Mutanabbi Street is located in the street.[11] It was noted that in the early days of Iraq, there were no areas in the city that were considered respectable so politicians and the educated class hung out in coffeehouses. An example of this is al-Zahawi Cafe which in 1932, the influential Bengali poet and philosopher, Rabindranath Tagore, had visited the street and al-Zahawi Café.[12][13]

During the 1920s, groups of Egyptian singers visited the country and helped develop the artistic movement that was happening in the country. As such, many singers such as Fayza Ahmed and Umm Kulthum gave concerts in the cinemas of the street. Umm Kulthum gave concerts in the Crescent Theater, a theater built in 1918 and located near al-Maidan Street, in 1932. Reportedly, ticket prices were high due to the amount of attention the concerts gave. Al-Istiqlal newspaper published an article about the visit entitled "The Magic of Babylon and the Pharaoh in the Crescent Club," and said that Umm Kulthum gave 12 concerts, starting from October 18, 1932.[1][14] Umm Kulthum left a large legacy and impact on the street and its artistic and social circles that her fans opened many Cafés that were themed after her at the time including one that survived to this day.[15] The street also saw new buildings being built such as the Abboud Building.[16] In 1946, the street was expanded and for its expansion, parts of the historic and ancient Murjan Mosque had to be demolished which got backlash from scholars. Nevertheless, the mayor of Baghdad, Arshad al-Umari, demolished parts of the mosque, including its madrasa and dome that included its builders' tomb below. Walls were built around the mosque to preserve and were connected to the street.[17]

Cinemas and theatres have started to materialize in Baghdad beginning in the 1930s and al-Rasheed Street was filled with them. Cinemas played a large major role in Iraqi society and Baghdadi cinemas used to distribute weekly advertisements for movies in both Arabic and English. At the time, going to cinemas was a weekly event for both the working and the middle class. Thursday became the traditional day of the week in which Baghdadi families went to theatres and also acted as a break day for students.[18]

During the 1940s, in the center of al-Rasheed Street, two cafes appeared in a style unfamiliar to the people of Baghdad. These were the Brazilian Café and the Swiss Café and were Western in terms of style instead of the traditional Iraqi style. This was due to the fact that many of their pioneers studied art in European cities such as Rome, and Paris. Those two cafés contributed to the start of a new modern artistic movement as well as contributed to the founding of the Union of Iraqi Writers which was established in 1952. Despite the fact that the pioneers of the more modern and Westernized cafes did not appreciate the traditional cafés that were widely spread throughout the city at the time, they were closely related to their fellow writers and artists. Political differences of opinion and viewpoints have never spoiled the sense of friendship between people.[19]

During the 14 July Revolution, the 1958 military coup that overthrew the Iraqi Monarchy, the Crown Prince Abd al-Ilah's dead corpse was dragged along the street and then cut to pieces.[20] That day, the street was full of demonstrations and marches. During the afternoon of that same day, many bodies were dragged into the street including the body of a Jordanian delegation from the Hashemite Federal Parliament who happened to be on a visit to Iraq was dragged through the area with a stick being shoved into his bottom while the crowded shouted for the capture of Muhammad Fadhel al-Jamali, the former-Iraqi Minister of Foreign Affairs. Iraq and Jordan were united into the Arab Federation at the time.[21]

The following year, Abd al-Karim Qasim, who lead the revolt that overthrew the Monarchy, narrowly avoided death in a botched assassination attempt orchestrated by a young Saddam Hussein.[20] Qasim was taken to the hospital and along with one of his companions who was also wounded, and his driver who was killed.[22]

- 20th century pictures of al-Rasheed Street

Al-Rasheed Street along with al-Ahmadiya Mosque in 1932.

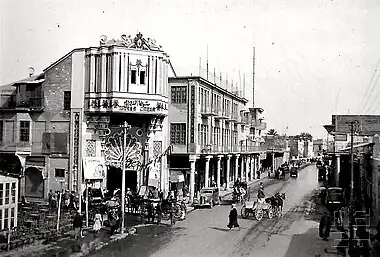

Al-Rasheed Street along with al-Ahmadiya Mosque in 1932. Al-Zawra'a Cinema in al-Rasheed Street in 1942.

Al-Zawra'a Cinema in al-Rasheed Street in 1942.

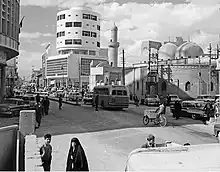

Al-Rasheed Street in 1961 along with the Haydar-Khana Mosque.

Al-Rasheed Street in 1961 along with the Haydar-Khana Mosque.

Architecture

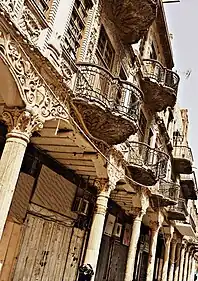

Baghdad is famous for its architecture and al-Rasheed Street is known for its architecture. The street includes building architecture partially inspired by Renaissance architecture and was characterized by renewed and delicate designs with curved lines and shapes inspired by plants and Geometric shapes and this appears in the inscriptions and decorations. The street includes shanasheel, an Islamic balcony that goes back to the Abbasid Era, which extends throughout the street and includes stained glass. The shanasheel of the street represents an architectural masterpiece and a mixture of art, architecture, civilization, and architectural heritage according to its inhabitants.[23][24][25][26]

Along the street are sidewalks which include arcades built in order to shade the pedestrians from the sun. three-story buildings are common along the street too.[6] The street also included more modern buildings such as the Abboud Building which was characterized by its strange circular shape.[27]

The Haydar-Khana Mosque, located in the street, is considered one of the most perfect and beautiful mosques in Baghdad due to its architecture. It has a massive blue dome with arabesque paintings on it.[7]

Notable landmarks and historical sites

Al-Rasheed Street includes many notable landmarks and sights of interest throughout its existence, some dating back to before the construction of the street. These include:

Coffeehouses

Cafés in Baghdad were considered social and intellectual houses for many social classes. As such, the city has an abundance of cafés and a lot of them are located on al-Rasheed Street. These consist of al-Zahawi Café, Arif Agha Café, Hassan Ajami Café, the Parliament Café, the Brazilian Café, Hajj Khalil Café, Umm Kulthum Café, the Swiss Café, and many more.[12][28] But for the sake of this list, we'll only list the most notable of these cafés.

- The Brazilian Café (Arabic: مقهى البرازيلية) was one of the most famous and oldest cafés in Baghdad that was established in the 1940s. The café served coffee that was imported from outside and was a meeting place for college students, the educated class, writers, and poets. In this café, Iraqi artist Jawad Saleem wrote in his memoirs after meeting Polish artists, where he wrote: "Now I know color, now I know drawing."[12]

- Hajj Khalil Café (Arabic: مقهى الحاج خليل) was a café that once existed in front of the gate of al-Mutanabbi Street near the Haydar-Khana Mosque. It was owned by Hajj Khalil al-Qahwati, a veteran of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War that was recognized in Baghdad for his Baghdadi characteristics, hospitality, and respectable attitude. The café has been visited by many of the educated class, as well as military personals and politicians. The café has also been received by many leaders of Iraq including King Ghazi and Abd al-Karim Qasim. The café has also been featured in the 1957 Iraqi movie Saeed Effendi in a minor role. The café closed in 1970 in order to demolish the building that housed it.[29]

- Hassan Ajami Café (Arabic: مقهى حسن عجمي) is an old preserved café that dates back to 1917 and is located opposite the Haydar-Khana Mosque. It was distinguished by its rare Russian samovars, decorated with pictures of Russian tsars and official seals dating back to the 19th century, along with teapots and hookah glasses, which were decorated with pictures of King Faisal I, King Ghazi and the Persian kings of the Qajars.[30]

- Umm Kulthum Café (Arabic: مقهى ام كلثوم) is an old preserved Café on the street themed after the Egyptian singer of the same name. Umm Kulthum enjoyed great popularity among the artistic, social, and political circles during her two visits to Iraq in 1932 and 1946 which led to many Cafes around the country that bore her name opening although only one remains today in al-Rasheed Street. Located near al-Maidan Square, the Café was opened in 1968 and was populated by fans of Umm Kulthum who listened to her songs in the café. The Café includes pictures of Umm Kulthum along with other figures such as King Faisal II. Despite the threat of closing, the Café remains crowded on Saturdays, a traditional day for friend gatherings in Baghdad.[15][31][32]

- Al-Zahawi Café (Arabic: مقهى الزهاوي) is one of the oldest surviving cafés in Baghdad, located near al-Mutanabbi Street. It was established in 1917 and was named after Iraqi poet and philosopher Jamil Sidqi al-Zahawi who was also one of the pioneers of the café. Over the decades, it was the home of many intellectuals, poets, singers, and journalists whose pictures fills the interior of the café.[5][33]

Places of worship

Due to the area the street is located in, many mosques can be found along the street.

- The Haydar-Khana Mosque (Arabic: جامع الحيدر خانة) is one of the oldest mosques in Iraq. The Mosque was established by Abbasid Caliph al-Nasir and is located near al-Mutanabbi Street. It is considered one of the most beautiful and perfect mosques in Baghdad in terms of engineering and architectural construction with its three domes and tall minaret along with calligraphy done by the Iraqi master Calligrapher Hashem Muhammad al-Baghdadi. It is also considered important for its contribution to revolutionary ideas against British colonialism in Iraq. Despite its importance, the mosque currently needs specialized maintenance and consultation due to neglect.[7]

- The Murjan Mosque (Arabic: جامع مرجان) is one of the oldest surviving mosques in Baghdad. It is an important religious and scientific landmark because it contains a madrasa within its corridors, in addition to the presence of the tombs of a number of sheikhs who studied in the Madrasa. Its walls used to be connected to the street but they were then demolished to expand the street. Despite its significant importance, currently, the mosque suffers from neglect.[5][34]

- Syed Sultan Ali Mosque (Arabic: جامع سيد سلطان علي) is an old mosque located on the street. It contains two madrasas that teach rational and literal sciences and a big library that holds rare manuscripts and printed books.[35]

Cinemas

Al-Rasheed Street used to be filled with cinemas and theatres. Baghdad, along with Cairo and Beirut, was one of the only Middle Eastern cities that imported American movies that were shown in theatres and cinemas. The movies that were imported and shown included movies from Warner Brothers, 20s Century Fox Studios, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Universal and Columbia Pictures as well as other Arab movies. The street included cinemas such as the Roxy Winter Cinema, the Roxy Summer Cinema, al-Zawra'a Cinema, the Rex Cinema, the Broadway Cinema (which later changed its name to Aladdin Cinema), al-Watan Cinema (later converted into a theater for the plays of Jassem Sharaf), al-Rasheed Cinema, al-Rafidain Summer Cinema, the Royal Cinema, the Central Cinema, al-Hamra Cinema, the Cairo Summer Cinema and al-Sharq Cinema which was later demolished.[36][37]

- The Crescent Theater (Arabic: مسرح الهلال) is an ancient theatre located in al-Maidan Square built in 1918. The theater is associated with Umm Kulthum who performed her first concert in Baghdad in 1932. Due to neglect in recent years, the theater's shanasheel collapsed in early 2023.[14]

- Al-Zawra'a Cinema (Arabic: سينما الزوراء) was one of the oldest cinemas in Iraq, opening in the 20th century. It used to draw huge crowds to popular Iraqi films, especially during the 60s as Iraq had a thriving private movie industry during the period. After the United Nations imposed broad sanctions on Iraq in 1990, the cinema industry quickly went into steep decline. New equipment, film, and chemicals for film laboratories were forbidden under new import rules designed to curb Saddam Hussein's chemical programs. No films have been made since and al-Zawra'a Cinema has since been deserted.[38]

Other notable sites

- The Abboud Building (Arabic: عمارة عبود) is one of the most iconic buildings on the street located at the entrance to Shorja on the side of the street near the Murjan Mosque. It is distinguished by its modern design in its age and circular shape.[27]

- The Abd al-Karim Qasim Museum is located on this street. The museum is dedicated to Abd al-Karim Qasim the former Iraqi Prime Minister and showcases his personal belongings, as well as gifts, weapons, archives, and documents. The museum's buildings are also notable for their building and architecture which includes the traditional Iraqi shanasheel. The museum is the first of its kind in Baghdad.[39][26]

- The Chakmakchi Company for Recording Musical and Lyrical CDs (Arabic: شركة جقماقجي لتسجيل الأسطوانات الموسيقية والغنائية) was an ancient Iraqi institution founded in 1918 and located at the beginning of al-Rasheed Street from the eastern door side. The company was founded in Mosul by the Chakmakchi family and opened a second branch on al-Rasheed Street in Baghdad in 1940. The company preserved Iraq's musical and artistic history through its records, which it recorded for the masters of Iraqi singing, such as Muhammad al-Qubanchi, Nazem al-Ghazali, Hudiri Abu Aziz, Nasser Hakim, Salima Pasha, Afifa Iskandar and many others. The company didn't only care for Iraqi singers but also preserved other Arab singers such as Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, Muhammad Abdel Wahab, Farid al-Atrash, Fayza Ahmed, and others. The company has declined in the last two decades due to neglect and the emergence of cassette tapes and Bluetooth. It then saw theft and vandalism after the US invasion of the country in 2003 and its Baghdad headquarters has now since been turned into a clothing store.[1][40]

- The McKenzie Library (Arabic: مكتبة مكنزي) was a library that provided foreign literature and books that was founded in 1924 by a Scotsman named Kenneth Mackenzie who migrated to Iraq after World War I. The Iraqi government at the time wanted to provide a library that offered a variety of foreign publications due to high demand at the time. Between school and scientific books, in addition to books on travel, Arab and Islamic heritage, and others. For a while, the library became a great center for Islamic studies until its decline in the eighties, as a result of the high prices of foreign books and then the UN embargo. In the last two decades, the library was closed due to neglect and has since been replaced with a commercial store.[41][42]

- Located on the street is the statue of Ma'ruf al-Rusafi, a patriotic poet who played a role against the British occupation. The statue dedicated to him is located on a square in the street named after him.[43]

- Photos of various sites on the street

Old houses on the street

Old houses on the street Al-Rafidain Bank on the street

Al-Rafidain Bank on the street

Modern era and preservation status

The first attempt to restore the street and return to its historical position was in 2001 under the leadership of Saddam Hussein who had ordered the restoration of the Syed Sultan Ali Mosque located on the outskirts of the street the year before. The municipality of Baghdad announced a campaign to develop and organize al-Rasheed Street. Mayor of Baghdad, Adnan Abd al-Hameed al-Douri, made it clear that the campaign aims to make the street a social, commercial, and political movement as it was in the past, and it also falls within the framework of a broad plan to develop and organize Baghdad. This campaign was launched due to the hardships Baghdad had gone through due to the UN sanctions on Iraq and the decline of the street due to the sanctions. Although many of the establishments, such as the Brazilian Café, survived the decline.[44]

After the US invasion of Iraq, many of the country's landmarks suffered from neglect and damage and are under threat of destruction, including al-Rasheed Street and its landmarks. The street saw a decline as a general social and intellectual location during the embargo on the country and many of its shop owners have since fled the country although many Iraqis have accused the government of neglect and ignoring the street's heritage. Reportedly, the street saw many buildings damaged by bullets due to the infighting between its people and clashes that had happened. Over the years, there have been a lot of attempts to restore and preserve the street and to turn it back into an important street and a tourist site although several issues hindered it. According to the Municipality of Baghdad, 80% of the street buildings are owned by citizens and not by the state, so an agreement must be reached with them. As of 2018, 30% of the street's buildings have been restored. The Municipality was criticized for the restoration attempt due to having no architects, conservationists, or architecture historians working on the street. The street has also witnessed protests that demand the preservation of Iraqi heritage, reportedly sixteen protesters have died since.[7][11][45][20][46][47]

Additionally, due to the invasion and sectarian violence that followed, the street became a victim of several bombing incidents that were planted near it, the last was in 2016 which killed more than two dozen people.[31] Many of the famous shops on the streets that used to sell clothes were turned into shops selling tools, industrial supplies, and tools needed by construction workers, in parallel with the spread of shops selling electricity generators due to the electricity situation in Iraq after 2003. Cafés on the streets such as the Parliament Café and the Brazilian Café also became shops selling electrical appliances and hardware. The cinema halls for al-Zawra'a and the Royal Cinema have been turned into large wards in the 2000s.[3] The Murjan Mosque, located in the middle of the street, has also been neglected and turned into a waste dump. Plenty of random ceilings and basements around the mosque were added which obscured the view of the mosque.[17]

In 2015, the Abd al-Karim Qasim Museum was opened after the former house of Halil Kut was restored in order to preserve the history of the era. The museum includes a lot of his belongings and gifts he received.[39]

In early 2023, the Crescent Theater, the theatre where Umm Kulthum held her concerts in the street, collapsed. Activists and bloggers documented the collapse and took pictures. The pictures circulated around Iraqi Social Media and showcased the destruction of the shanasheel of the theater along with other insides of the building. The pictures caused great anger among Iraqis who saw the destruction as neglect of the theater that carries a great heritage legacy and some warned that it would become a commercial theatre in the future. The event helped revive calls for the restoration of the heritage sites of Baghdad that are under threat of neglect.[14]

In March 2023, Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia' al-Sudani stressed the importance of preserving the ancient parts of Baghdad. The Prime Minister started a project to preserve the old parts of the city which includes al-Rasheed Street as well as al-Rusafa Square and al-Maidan Square. He stressed that the rehabilitation process will include heritage buildings and transforming them into Baghdadi sessions, cultural and social meetings, and an economic interface. The development began after the Eid al-Fitr of 2023. Despite the delay and the project's length of time, the development project was perceived as a step towards preserving the past of the city and becoming an economic and social area once again.[2]

See also

- Abu Nuwas Street

- Café culture of Baghdad

- Al-Fitah Street

- Al-Jumhuriya Street

- Al-Mutanabbi Street

- Al-Mu'izz Street

References

- جواد, قحطان جاسم. "أم كلثوم ونجيب الريحاني وبديعة مصابني قدموا أبرز أعمالهم على مسارحه.. جولة في شارع الرشيد في بغداد في ذكرى تأسيسه". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- The rehabilitation campaign for al-Rasheed al-Baghdadi Street begins after al-Adha, 2023

- الكويتية, جريدة الجريدة (2007-11-01). "شارع الرشيد في بغداد... إمبراطورية مهدّدة بالزوال". جريدة الجريدة الكويتية (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- "Baghdad wants 100-year-old street on UNESCO heritage list - Iraqi News". 2021-05-08. Archived from the original on 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- "الگاردينيا - مجلة ثقافية عامة - شارع الرشيد.. حكايات وطرائف..جولة في الشارع في سنواته الاولى". www.algardenia.com. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- Elsheshtawy, Yasser (2004-08-02). Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An Urban Kaleidoscope. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-41010-1.

- "الحيدر خانة تتكسر معالمه ووزارة الثقافة تعلّق بإحباط على إعمار محتضن قادة ثورة العشرين! » وكالة بغداد اليوم الاخبارية". وكالة بغداد اليوم الاخبارية (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- "الحيدر خانة.. ذاكرة دينية ورمزية سياسية بالعراق". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- "Iraqi Ministry of Electricity". Archived from the original on 2009-04-02.

- "ما سر الرقم 4 في شارع الرشيد وسط بغداد ؟". www.mawazin.net. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- Al-Rasheed Street in Baghdad tells the story of a country tired of bullets, 2020

- "الگاردينيا - مجلة ثقافية عامة - مقاهي بغداد ... ذاكرة المكان وملتقى الثقافة". www.algardenia.com. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- "الگاردينيا - مجلة ثقافية عامة - مقهى الزهاوي ، واحة من واحات الفكر والادب". www.algardenia.com. Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- "المسرح الذي غنت فيه أم كلثوم.. سقوط ذاكرة من الفن العراقي". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- "مقهى أم كلثوم في بغداد ما زال محافظاً على عهدها رغم تغيير اسمه". aawsat.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- "عمارة ادفيش عبود .. استحضار الماضي حداثياً". 2022-12-31. Archived from the original on 2022-12-31. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "الگاردينيا - مجلة ثقافية عامة - حول تاريخ جامع مرجان .. واكذوبة قصة الايطالي موركان! وحالة". www.algardenia.com. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- "دور السينما في بغداد ايام زمان". www.almadasupplements.com. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- "مقاهٍ غير تقليدية في بغداد: المقهى البرازيلية والسويسرية و"الكيت كات" كنماذج ثلاثة". 2020-08-05. Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Century ago and today, Baghdad street a front line in revolt". AP NEWS. 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- "ذكريات عن الشارع وأشياءه – جريدة الصباح الجديد". newsabah.com. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- "حدث في مثل هذا اليوم: محاولة فاشلة لاغتيال الزعيم قاسم". almadapaper.net. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- الكناني, جبار. ""شناشيل العراق".. عودة إلى التصميمات التراثية الأصيلة". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- https://www.ina.iq/120798--.html

- "عراقٌ انا | الشـناشـيل ج2". عراقٌ انا (in Arabic). 2017-06-21. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- "هيئة السياحة العراقية". 2017-08-13. Archived from the original on 2017-08-13. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- "الـزمـان - طبعة العراق - رحلة في ذاكرة شارع الرشيد على بساط الريح من بغداد إلى الدنيا". 2022-12-31. Archived from the original on 2022-12-31. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Unconventional cafes in Baghdad: Brazilian, Swiss, and Kit Kat as three models, 2014

- "بغداديات (مقهى خليل) ذكريات وانطباعات". ISBNiraq.org (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- "مقاهي بغداد.. ذاكرة المكان وملتقى الثقافة". 2018-07-31. Archived from the original on 2018-07-31. Retrieved 2023-09-08.

- 王淑卿. "Once-bustling Baghdad cafe district fades away after war". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- Umm Kulthum is present in Baghdad at the “Legendary” Café, 2021

- "مقهى الزهاوي في بغداد.. "أغانٍ هابطة" تغلق ملتقى المشاهير". alwatannews.net. 2022-06-07. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- "العراق.. استياء لتحوّل جامع مرجان الأثري إلى مكب نفايات". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- The Baghdadis, their news and councils - authored by Ibrahim Abd al-Ghani al-Droubi - Baghdad 1958 AD - page 291

- "الگاردينيا - مجلة ثقافية عامة - دور السينما في بغداد الأمس". www.algardenia.com. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- "AL-MADA Daily Newspaper...جريدة المدى". almadapaper.net. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- McCarthy, Rory (2002-11-15). "Baghdad's dusty silver screens". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- "افتتاح أول متحف من نوعه في بغداد للزعيم عبد الكريم قاسم | الشارع العراقي". 2016-12-29. Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "الگاردينيا - مجلة ثقافية عامة - آل جقماقجي ....أول شركة تسجيل في العراق". www.algardenia.com. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- "هكذا تأسست مكتبة مكنزي". www.almadasupplements.com. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- "McKenzie Library": Another firefight on al-Rasheed Street, 2016

- "الگاردينيا - مجلة ثقافية عامة - شارع الرشيد في بغداد يروي حكاية وطن أتعبه الرصاص". www.algardenia.com. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- "أمانة بغداد تستعد لإعادة شارع الرشيد لمكانته التاريخية". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- Al-Rasheed... The oldest street in Baghdad is groaning under the weight of neglect, 2018

- "شارع الرشيد ببغداد.. حين تتداعى ذكريات العراقيين". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- "شارع الرشيد أو قلب بغداد.. حزيناً يبدأ قرنه الثاني | Irfaasawtak". www.irfaasawtak.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-10.

Further reading

- Al-Qaisi, Hamid (2014) "Baghdadiyyat (Khalil Café) Memories and Impressions." Dar al-Zakira for Publishing and Distribution.