al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (/ælmænˈsʊər/; Arabic: أبو جعفر عبد الله بن محمد المنصور; 95 AH – 158 AH/714 CE – 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab al-Manṣūr (المنصور) was the second Abbasid caliph, reigning from 136 AH to 158 AH (754 CE – 775 CE) succeeding his brother al-Saffah (r. 750–754). He is known for founding the 'Round City' of Madinat al-Salam, which was to become the core of imperial Baghdad.

| al-Mansur المنصور | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khalifah Amir al-Mu'minin | |||||

.JPG.webp) Gold dinar of al-Mansur | |||||

| 2nd Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 10 June 754 – 6 October 775 | ||||

| Predecessor | al-Saffah | ||||

| Successor | al-Mahdi | ||||

| Born | c. 714 al-Humayma, Jordan | ||||

| Died | 6 October 775 (aged 61) near Mecca, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | ||||

| Father | Muhammad ibn Ali | ||||

| Mother | Sallamah | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Modern historians regard al-Mansur as the real founder of the Abbasid Caliphate, one of the largest polities in world history, for his role in stabilizing and institutionalizing the dynasty.[1]: 265

Background and early life

According to al-Suyuti's History of the Caliphs, al-Mansur lived 95 AH – 158 AH (714 CE – 6 October 775 CE).[2] Al-Mansur was born at the home of the Abbasid family in Humeima (modern-day Jordan) after their emigration from the Hejaz in 714 (95 AH).[3] His mother was Sallamah, a Berber slave woman.[4] Al-Mansur was a brother of al-Saffah.[5] Both were named Abd Allah, and to distinguish between them, al-Saffah was referred to by his kunya Abu al-Abbas.[6]

Al-Mansur was a great great-grandson of Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, an uncle of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad.[7] Al-Mansur's brother al-Saffah began asserting his claim to become caliph in the 740s and became particularly active in Khorasan, an area where non-Arab Muslims lived. After the death of the Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 743 a period of instability followed. Al-Saffah led the Abbasid Revolution in 747 and his claim to power was supported throughout Iraq by Muslims. He became the first caliph of the Abbasid caliphate in 750 after defeating his rivals.[5]

Shortly before the overthrow of the Umayyads by an army of rebels from Khorasan that were influenced by propaganda spread by the Abbasids, the last Umayyad Caliph Marwan II, arrested the head of the Abbasid family, Al Mansur's other brother Ibrahim. Al-Mansur fled with the rest of his family to Kufa where some of the Khorasanian rebel leaders gave their allegiance to his brother al-Saffah. Ibrahim died in captivity and al-Saffah became the first Abbasid Caliph. During his brother's reign, al-Mansur led an army to Mesopotamia where he received a submission from the governor after informing him of the last Umayyad Caliph's death. The last Umayyad governor had taken refuge in Iraq in a garrison town. He was promised a safe-conduct by al-Mansur and the Caliph al-Saffah, but after surrendering the town, he was executed with a number of his followers.[3]

According to The Meadows of Gold, a history book in Arabic written around 947 CE, al-Mansur's dislike of the Umayyad dynasty is well documented and he has been reported saying:

"The Umayyads held the government which had been given to them with a firm hand, protecting, preserving and guarding the gift granted them by God. But then their power passed to their effeminate sons, whose only ambition was the satisfaction of their desires and who chased after pleasures forbidden by Almighty God...Then God stripped them of their power, covered them with shame and deprived them of their worldly goods".[8]: 24

Mansur's first wife was a Yemeni woman from a royal family; his second was a descendant of a hero of the early Muslim conquests; his third was an Iranian servant. He also had a minimum of three concubines: an Arab, a Byzantine, nicknamed the “restless butterfly," and a Kurd.[9]

Caliphate

Al-Saffah died after a short five-year reign and al-Mansur took on the responsibility of establishing the Abbasid caliphate[3] by holding on to power for nearly 22 years, from Dhu al-Hijjah 136 AH until Dhu al-Hijjah 158 AH (754 – 775).[8][10] Al-Mansur was proclaimed Caliph on his way to Mecca in the year 753 (136 AH) and was inaugurated the following year.[11] Abu Ja'far Abdallah ibn Muhammad took the name al-Mansur ("the victorious") and agreed to make his nephew Isa ibn Musa his successor to the Abbasid caliphate. This agreement was supposed to resolve rivalries in the Abbasid family, but al-Mansur's right to accession was particularly challenged by his uncle Abdullah ibn Ali. Once in power as caliph, al-Mansur had his uncle imprisoned in 754 and killed in 764.[12]

Execution of Abu Muslim and aftermath

Fearing the power of the Abbasid army general Abu Muslim, who gained in popularity among the people, al-Mansur carefully planned his assassination. Abu Muslim was conversing with the Caliph when, at an appointed signal, four (some sources say five) of his guards rushed in and fatally wounded the general.[13] John Aikin, in his work General Biography, narrates that Mansur, not content with the assassination, committed "outrages on the dead body, and kept it several days in order to glut his eyes with the spectacle."[11]

The Execution of Abu Muslim caused uproars throughout the province of Khorasan. In 755 Sunpadh an Iranian nobleman from the House of Karen, led a revolt against al-Mansur, taking the cities of Nishapur, Qumis, and Ray. In Ray, he seized the treasuries of Abu Muslim. He gained many supporters from Jibal and Tabaristan, including the Dabuyid ruler, Khurshid, who was paid with money from the treasures.[13]: 201 Al-Mansur ordered a force of 10,000 under Abbasid commander Jahwar ibn Marrar al-lijli to march without delay to Khorasan to fight the rebellion. Sunpadh was defeated and Khorasan reclaimed by the Abbasids.[13]

Al-Mansur sent an official to take inventory of the spoils collected from the battle as a precautionary measure against acquisition by his army. Angered by al-Mansur's avarice, general Jahwar gained support from his troops for his plans to split the treasures evenly, and revolted against the caliph. This raised alarm in the caliph's court and al-Mansur ordered Mohammad ibn Ashar to march towards Khorasan. Jahwar, knowing his troops were at a disadvantage, retired to Isfahan and fortified in preparation. Mohammad's army pressed the rebel forces and Jahwar fled to Azerbaijan. Jahwar's forces were defeated, but he escaped Mohammad's pursuit. This campaign lasted from 756 to 762 CE (138 to 144 AH).[13]

After relieving former vizier ibn Attiya al-Bahili, al-Mansur transferred his duties to Abu Ayyub al-Muriyani from Khuzestan. Abu Ayyub was previously a secretary to Sulayman ibn Habib ibn al-Muhallab, who in the past, had condemned al-Mansur to be whipped and flogged to pieces. Abu Ayyub had rescued al-Mansur from this punishment. Nevertheless, after appointing him as vizier, al-Mansur suspected Abu Ayyub of various crimes, including extortion and treachery, which led to the latter's assassination. The vacant secretary role was granted to Aban ibn Sadaqa until the death of the caliph al-Mansur.[8]: 26

Foundation of Baghdad

In 757 CE, al-Mansur sent a large army to Cappadocia which fortified the city of Malatya. In this same year, he confronted a group of the Rawandiyya from the region of Greater Khorasan that were performing circumambulation around his palace as an act of worship.[14][11]: 201 When in 758/9 the people of Khorasan rioted against al-Mansur in the battle of Al Hashimiya, Ma'n ibn Za'ida al-Shaybani, a general from the Shayban tribe and companion of Yazid ibn Umar al-Fazari, the Umayyad governor of Iraq, appeared at the scene of the uprising completely masked, and threw himself between the crowd and Mansur, driving the insurgents away. Ma'n reveals himself to al-Mansur as "he whom you have been searching" and upon hearing this, al-Mansur granted him rewards, robes of honor, rank, and amnesty from previously serving the Umayyad dynasty.[8]: 23 In 762 two descendants of Hasan ibn Ali rebelled in Medina and Basra. Al-Mansur's troops defeated the rebels first in Medina and then in Basra. This would be the last major uprising against the caliph al-Mansur.[15]

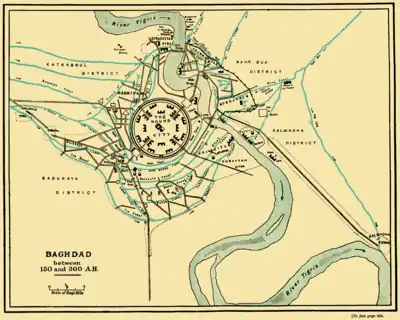

To consolidate his power al-Mansur founded the new imperial residence and palace city Madinat as-Salam (the city of peace), which became the core of the Imperial capital Baghdad.[16] Al-Mansur laid the foundations of Baghdad near the old capital of al-Mada'in, on the western bank of the Tigris River, a location acceptable to him and his commanders. The circular city of about 2.4 km diameter was enclosed by a double-thick defensive wall with four gates named Kufa, Syria, Khorasan, and Basra. In the center of the city al-Mansur erected the caliph's palace and the main mosque.[17] Al-Mansur had built Baghdad in response to a growing concern from the chief towns in Iraq, Basra, and Kufa that there was lack of solidity within the regime after the death of Abu'l 'Abbas (later known as al-Saffah). Another reason for the construction of the new capital was the growing need to house and provide stability for a rapidly developing Abbasid bureaucracy forged under the influence of Iranian ideals.[3] The medieval historians al-Tabari and al-Khatib al-Baghdadi would later claim that al-Mansur had ordered the demolition of the Khosrow palace in Ctesiphon so that the material could be used for the construction of the city of peace.[18]

Al-Mansur pursued his vision of a powerful centralized caliphate in the new Muslim imperial capital of Baghdad. The city was populated with men and women of different faiths and cultures from all over the Islamic world. The Baghdad populace included Christian, Zoroastrian and Jewish minorities and communicated in Arabic. Al-Mansur pursued Islamization by staffing his administration with Muslims of varied backgrounds.[19] Baghdad became one of al-Mansur's lasting achievements. His rule was largely peaceful as he focused on internal reforms, agriculture and patronage of the sciences,[17] thus he paved the way for Baghdad to become a global center of learning and science under the rule of the seventh Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun.[20]

In 764 al-Mansur's son al-Mahdi was made the designated heir to the caliphate, taking precedence over al-Mansur's nephew Isa ibn Musa, who had been named the designated successor when al-Mansur was crowned caliph. This change in succession was opposed by parts of the Abbasid family and some allies of Isa ibn Musa in Khurasan, but was supported by the Abbasid army. Al-Mansur had cultivated support for his son's accession since 754, while undermining Isa ibn Musa's position within the Abbasid military.[21]

Al-Tabari writes in his History of Prophets and Kings: "Abu Ja'far had a mirror in which he could descry his enemy from his friend."[22] Al-Mansur's secret service extended to remote regions of his empire, and were cognizant of everything from social unrest to the price of figs, making Mansur very knowledgeable of his domains. He rose at dawn, worked until evening prayer. He set the example for his son and heir. According to historic sources al-Mansur advised his son: “put not off the work of today until tomorrow and attend in person to the affairs of state. Sleep not, for thy father has not slept since he came to the caliphate. For when sleep fell upon his eyes, his spirit remained awake.” Notably frugal, al-Mansur was nicknamed Abu al-Duwaneek (“the Father of Small Change”), kept close tabs on his tax collectors, and made sure public spending was carefully monitored. He is reported as having said “he who has no money has no men, and he who has no men watches as his enemies grow great.”[23]

Islamic scholars under him

The Alids, a group descended from Muhammad's closest male relative and cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, had fought with the Abbasids against the Umayyads. They wanted the power to be given to the Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq, a great-grandson of Ali and one of the most influential scholars in Islamic jurisprudence at the time. When it became clear that the Abbasid family had no intention of handing the power to an Alid, groups loyal to Ali moved into opposition.[3] When al-Mansur came to power as second Abbasid caliph he started to suppress what he perceived as extreme elements in the broad Muslim coalition that had supported the Abbasid Revolution. He would be the first Abbasid caliph to uphold Islamic orthodoxy as a matter of public policy. While al-Mansur's regime did not intrude into the private realm of elites, orthodoxy was promoted in public worship, for example through the organization of pilgrim caravans.[24] Al-Mansur's harsh treatment towards the Alids led to a revolt in 762–763, but they were eventually defeated.[3]

Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq became the victim of harassment by the Abbasid family and in response to his growing popularity among the people was eventually poisoned on the orders of the caliph[25] in the tenth year of al-Mansur's reign.[8]: 26 According to a number of sources, Abu Hanifa an-Nu'man, who founded a school of jurisprudence, was imprisoned by al-Mansur. Malik ibn Anas, the founder of another school, was flogged during his rule, but al-Mansur himself did not condone this. Al-Mansur's cousin, the governor of Madinah at the time, had ordered the flogging and was punished for doing so.[26] Muhammad and Ibrahim ibn Abdallah, the grandsons of Imam Hassan ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammad, were persecuted by al-Mansur after rebelling against his reign. They escaped his persecution, but al-Mansur's anger fell upon their father Abdallah ibn Hassan and others of his family. Abdallah's sons were later defeated and killed.[11]: 202

Patronage for translations and scholarship

Al-Mansur was the first Abbasid caliph to sponsor the Translation Movement. Al-Mansur was particularly interested in sponsoring the translations of texts on astronomy and astrology.[27] Al-Mansur called scientists to his court and became noted as patron of astronomers.[28] When al-Mansur's Baghdad court was presented with the Zij al-Sindhind, an Indian astronomical handbook that included tables to calculate celestial positions, al-Mansur ordered for this major Indian work on astronomy to be translated from Sanskrit to Arabic. The astronomical tables in the Arabic translation of Zij al-Sindhind became widely adopted by Muslim scholars. During al-Mansur reign Greek works were also translated, such Ptolemy's Almagest and Euclid's Elements.[29]

Al-Mansur had Persian books on astronomy, mathematics, medicine, philosophy and other sciences translated in a systematic campaign to collect knowledge.[30] The translation of Persian books was part of a growing interest in ancient Iranian heritage and a Persian revivalist movement which al-Mansur sponsored. The translation and study of works in Pahlavi, a pre-Islamic language of Persia, became fashionable among intellectuals and authors who supported the Abbasid caliphate.[31] Government secretaries of Persian descent in al-Mansur's administration sponsored translations of Pahlavi texts on the history and principles of royal administration. Popular Arabic translations were produced by Ibn al-Muqaffa of texts that documented the systems and hierarchies of the Sasanian Empire.[32]

Al-Mansur was greatly interested in the quality of the translation and paid al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf ibn Maṭar to translate Euclid's Elements twice.[29] Al-Mansur paid for the physician Jabril ibn Bukhtishu to write Arabic translations of medical books,[29] while the first Arabic translations of medical texts written by Galen and Hippocrates were done by al-Mansur's official translator.[33] In 765 al-Mansur suffered from a stomach ailment and called the Christian Syriac-speaking physician Jurjis ibn Bukhtishu from Gundeshapur to Baghdad for medical treatment. In doing so al-Mansur started the tradition among Abbasid caliphs, who would pay physicians of the Nestorian Christian Bukhtishu family to attend to their needs and to write original Arabic medical treatises, as well as translate medical texts into Arabic.[34]

Foreign policy

In 751 the first Abbasid caliph al-Saffah had defeated the Chinese Tang dynasty in the Battle of Talas. Chinese sources record that al-Mansur sent his diplomatic delegations regularly to China. Al-Mansur's delegations were known in China as Heiyi Dashi (Black Clothed Arabs).[36] In 756 al-Mansur sent 3,000 mercenaries to assist Emperor Suzong of Tang in the An Lushan rebellion.[37] A massacre of foreign Arab and Persian Muslim merchants by former Yan rebel general Tian Shengong happened during the An Lushan rebellion in the Yangzhou massacre (760),[38][39]

The Byzantine emperor Constantine V had used the weakness of the Umayyad caliphate to regain land from Muslim rulers. After the Umayyad caliphate was defeated by al-Mansur's predecessor al-Saffah, Constantine V invaded Armenia and occupied parts of it throughout 751 and 752. Under al-Mansur's rule Muslim armies conducted raids on Byzantine territory.[40] Al-Mansur was the first Abbasid caliph to hold a ransom meeting with the Byzantine Empire. Diplomats in the service of Constantine V and al-Mansur first negotiated the exchange of prisoners in 756.[41]

In 763 al-Mansur sent his troops to conquer al-Andalus for the Abbasid empire. But the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Rahman I successfully defended his territory. Al-Mansur withdrew and thereafter focused his troops of holding the eastern part of his empire on lands that were once part of Persia.[42]

Some historians credit al-Mansur with starting the Abbasid–Carolingian alliance. In fact, it was the first Carolingian king Pippin III who initiated a new era of Franconian diplomacy by sending diplomatic envoys to al-Mansur's Baghdad court in 765. It is probable that Pippin III sought an alliance with al-Mansur against their common enemies, the Emirate of Córdoba. In 768 the envoys of Pippin III returned to Francia along with caliph al-Mansur's ambassadors. Pippin III received al-Mansur's delegation in Aquitaine and gifts were exchanged as a sign of the new alliance. This alliance was solidified when between 797 and 807 king Charlemagne and caliph Harun al-Rashid established embassies.[43]

Al-Mansur's treatment of his Christian subjects was severe; he "collected from them capitation with much vigor and impressed upon them marks of slavery."[11]: 202

Family

Al-Mansur's first wife was Arwa known as Umm Musa, whose lineage went back to the kings of Himyar.[44] Her father was Mansur al-Himyari. She had a brother named Yazid.[45] She had two sons, Muhammad (future Caliph al-Mahdi) and Ja'far.[44] She died in 764.[44] Another wife was Hammadah. Her father was Isa,[46] one of al-Mansur's uncles.[47] She died during al-Mansur's caliphate.[46] Another wife was Fatimah. Her father was Muhammad, one of the descendants of Talhah ibn Ubaydullah. She had three sons, Sulayman, Isa, and Ya'qub.[45] One of his concubines was a Kurdish woman. She was the mother of al-Mansur's son Ja'far 'Ibn al-Kurdiyyah' (Nasab translating to "Son of the Kurdish woman"). Unlike his other adult half-brothers, little is known of Ja'far and he likely was not involved in politics or had marriage or issue. However, his death is recorded at 802 AD by palace records suggesting he lived into adulthood and continued to live at court rather than having been banished or dying before adulthood.[45] Another concubine was Qali-al Farrashah. She was a Greek, and was the mother of al-Mansur's son Salih al-Miskin.[45] Another concubine was Umm al-Qasim, whose son al-Qasim died at aged ten.[45] Al-Masnur's only daughter Aliyah was born to an Umayyad woman. She married Ishaq ibn Sulayman.[45]

Death

Al-Mas'udi writes that Mansur died on Saturday 6, Dhu al-Hijja 158 AH/775 CE. There are varying accounts of the location and circumstances of al-Mansur's death. One account narrates that al-Mansur was on a pilgrimage to Mecca and had nearly reached, when death overtook him at a location called the Garden of the Bani Amir on the high road to Iraq at the age of sixty-three. According to this narration, he was buried in Mecca with his face uncovered because he was wearing the ihram clothing. 100 graves were dug around Mecca with the intention to thwart any attempt to find and violate his bones.[48]

A different narration from Fadl ibn Rabi'ah, who claimed to have been with Mansur at his time of death, states that he died at al-Batha' near the Well of Maimun in which he would have been buried at al-Hajun at sixty-five years of age. In this narration, Mansur was sitting in a domed room hallucinating about ill-omen writings on the wall. When al-Rabiah replied "I see nothing written on the wall. Its surface is clean and white," al-Mansur replied, "my soul is warned that she may prepare for her near departure." After reaching the Well of Maimun, he reportedly said "God be praised" and succumbed to death that very day.

When al-Mansur died, the caliphate's treasury contained 600,000,000 dirhams and fourteen million dinars.[8]: 33 On his deathbed, Mansur said, “We have sacrificed the life to come for a mere dream!”[49]

See also

- al-Rumiya, city used temporarily by al-Mansur as his seat

- Bay'ah Mosque is a mosque outside Mecca in Arabia, It was built on the orders of al-Mansur.

- Hasan ibn Zayd ibn Hasan Abbasid Governor of Medina 766 to 772.

- Ibn Ishaq

- Sino-Arab relations

References

- The Cambridge History of Islam, volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, ed. Chase F Robinson, March 2011

- Al-Souyouti, Tarikh Al-Kholafa'a (The History of Caliphs)

- Hawting, G.R. "Al Mansur: Abbasid Caliph". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Najībābādī, Akbar Shāh K̲h̲ān (2001). History of Islam (Vol 2). Darussalam. p. 287. ISBN 9789960892887.

- Tucker, Ernest (2016). The Middle East in Modern World History. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 9781315508245.

- El-Hibri 2021, p. 41.

- Adamec, Ludwig W. (2016). Historical Dictionary of Islam. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 17. ISBN 9781442277243.

- Sanders, P. (1990). The Meadows of Gold: The Abbasids by MAS‘UDI. Translated and edited by Lunde Paul and Stone Caroline, Kegan Paul International, London and New York, 1989 ISBN 0 7103 0246 0. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, 24(1), 50–51. doi:10.1017/S0026318400022549

- Bobrick 2012, p. 21.

- Axworthy, Michael (2008); A History of Iran; Basic, USA; ISBN 978-0-465-00888-9. p. 81.

- Aikin, John (1747). General biography: or, Lives, critical and historical, of the most eminent persons of all ages, countries, conditions, and professions, arranged according to alphabetical order. London: G. G. and J. Robinson. p. 201. ISBN 1333072457.

- Marsham, Andrew (2009). Rituals of Islamic Monarchy: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire. Edinburgh University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780748630776.

- Marigny, François Augier de (1758). The history of the Arabians, under the government of the caliphs, from Mahomet, their founder, to the death of Mostazem, the fifty-sixth and last Abassian caliph; containing the space of six hundred thirty-six years. With notes, historical, critical, and explanatory; together with genealogical and chronological tables; and a complete index to each volume. London: London, T. Payne [etc.] p. 23. ISBN 9781171019787. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- Berkey, J. P. (2003). The formation of Islam: Religion and society in the Near East, 600–1800. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Salvatore, Armando; Tottoli, Roberto; Rahimi, Babak (2018). The Wiley Blackwell History of Islam. John Wiley & Sons. p. 125. ISBN 9780470657546.

- Charles Wendell (1971). "Baghdad: Imago Mundi, and Other Foundation-Lore". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 2.

- Ghareeb, Edmund A.; Dougherty, Beth (2004). Historical Dictionary of Iraq. Scarecrow Press. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9780810865686.

- Jayyusi, Salma K.; Holod, Renata; Petruccioli, Attilio; Raymond, Andre (2008). The City in the Islamic World, Volume 94/1 & 94/2. BRILL. p. 225. ISBN 9789004162402.

- Salvatore, Armando; Tottoli, Roberto; Rahimi, Babak (2018). The Wiley Blackwell History of Islam. John Wiley & Sons. p. 126. ISBN 9780470657546.

- Ghareeb, Edmund A.; Dougherty, Beth (2004). Historical Dictionary of Iraq. Scarecrow Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780810865686.

- Marsham, Andrew (2009). Rituals of Islamic Monarchy: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire. Edinburgh University Press. p. 193. ISBN 9780748630776.

- al-Tabari; Williams, John Alden (1988). The Early 'Abbasi Empire, Volume I: The Reign of Abu Ja'far al-Mansur. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0521326621.

- Bobrick 2012, p. 13.

- Tucker, Ernest (2016). The Middle East in Modern World History. Routledge. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781315508245.

- al-Fusul al-muhimmah, p.212; Dala’il al-imamah, p.lll: Ithbat al-wasiyah, p.142.

- Ya'qubi, vol.III, p. 86; Muruj al-dhahab, vol.III, pp. 268–270.

- Bsoul, Labeeb Ahmed (2019). Translation Movement and Acculturation in the Medieval Islamic World. Springer. p. 82. ISBN 9783030217037.

- Bsoul, Labeeb Ahmed (2019). Translation Movement and Acculturation in the Medieval Islamic World. Springer. p. 85. ISBN 9783030217037.

- Bsoul, Labeeb Ahmed (2019). Translation Movement and Acculturation in the Medieval Islamic World. Springer. p. 88. ISBN 9783030217037.

- Bsoul, Labeeb Ahmed (2019). Translation Movement and Acculturation in the Medieval Islamic World. Springer. pp. 83–84. ISBN 9783030217037.

- Selim, Samah (2017). Nation and Translation in the Middle East. Routledge. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9781317620648.

- Selim, Samah (2017). Nation and Translation in the Middle East. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 9781317620648.

- al-Jubouri, Imadaldin (2004). History of Islamic Philosophy: With View of Greek Philosophy and Early History of Islam. Authors On Line Ltd. pp. 186–187. ISBN 9780755210114.

- Morelon, Régis (1916). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science: Technology, alchemy and life sciences. CRC Press. p. 910. ISBN 9780415124126.

- Grierson, Philip; Blackburn, Mark A. S.; Museum, Fitzwilliam (5 August 1986). Medieval European Coinage: With a Catalogue of the Coins in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521031776 – via Google Books.

- Visvizi, Anna; Lytras, Miltiadis D.; Alhalabi, Wadee; Zhang, Xi (2019). The New Silk Road leads through the Arab Peninsula: Mastering Global Business and Innovation. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 9781787566798.

- Needham, Joseph; Ho, Ping-Yu; Lu, Gwei-Djen; Sivin, Nathan (1980). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 416. ISBN 052108573X.

- Wan, Lei (2017). The earliest Muslim communities in China (PDF). Qiraat No. 8 (February – March 2017). King Faisal Center For Research and Islamic Studies. p. 11. ISBN 978-603-8206-39-3.

- Qi 2010, p. 221-227.

- Walker, Alicia (2012). Middle East Conflicts from Ancient Egypt to the 21st Century: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection [4 volumes]. Cambridge University Press. p. 258. ISBN 9781440853531.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2019). The Emperor and the World: Exotic Elements and the Imaging of Middle Byzantine Imperial Power, Ninth to Thirteenth Centuries C.E. ABC-CLIO. p. 40. ISBN 9781107004771.

- Wise Bauer, Susan (2010). The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 369. ISBN 9780393078176.

- Tor, Deborah (2017). The ʿAbbasid and Carolingian Empires: Comparative Studies in Civilizational Formation. BRILL. p. 85. ISBN 9789004353046.

- Abbott, Nabia (1946). Two Queens of Baghdad: Mother and Wife of Hārūn Al Rashīd. University of Chicago Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-86356-031-6.

- al-Tabari; Hugh Kennedy (1990). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 29: Al-Mansur and al-Mahdi A.D. 763-786/A.H. 146-169. SUNY series in Near Eastern Studies. State University of New York Press. pp. 148–49.

- al-Sāʿī, Ibn; Toorawa, Shawkat M.; Bray, Julia (2017). كتاب جهات الأئمة الخلفاء من الحرائر والإماء المسمى نساء الخلفاء: Women and the Court of Baghdad. Library of Arabic Literature. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-6679-3.

- Khallikān, Ibn; de Slane, W.M.G. (1842). Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary. Oriental translation fund of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 1. p. 535.

- Bobrick 2012, p. 16

- Bobrick 2012, p. 19

Sources cited

- Bobrick, Benson (2012). The Caliph's Splendor: Islam and the West in the Golden Age of Baghdad. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1416567622.

- El-Hibri, Tayeb (2021). The Abbasid Caliphate: A History. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-18324-7.

- Qi, Dongfang (2010), "Gold and Silver Wares on the Belitung Shipwreck", in Krahl, Regina; Guy, John; Wilson, J. Keith; Raby, Julian (eds.), Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds, Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 221–227, ISBN 978-1-58834-305-5, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2021, retrieved 9 July 2022

External links

Works by or about Al-Mansur at Wikisource

Works by or about Al-Mansur at Wikisource