Al-Mutanabbi

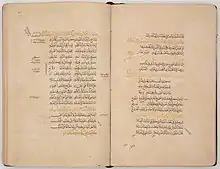

Abū al-Ṭayyib Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥusayn al-Mutanabbī al-Kindī (Arabic: أبو الطيب أحمد بن الحسين المتنبّي الكندي; c. 915 – 23 September 965 AD) from Kufa, Abbasid Caliphate, was a famous Abbasid-era poet at the court of the Hamdanid emir Sayf al-Dawla in Aleppo, and for whom he composed 300 folios of poetry.[1][2][3] His poetic style earned him great popularity in his time and many of his poems are not only still widely read in today's Arab world but are considered to be proverbial.

Al-Mutanabbi المتنبي | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Statue of Al-Mutanabbi in Baghdad | |

| Born | 915 |

| Died | 23 September 965 (aged approximately 50) |

| Other names | (أبو الطيب احمد بن الحسين المتنبّي) |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age (Middle Abbasid era) |

| Region | Arab world, Muslim world |

Main interests | Arabic poetry |

He started writing poetry when he was nine years old. He is well known for his sharp intelligence and wittiness. Among the topics he discussed were courage, the philosophy of life, and the description of battles. As one of the greatest, most prominent and influential poets in the Arabic language, much of his work has been translated into over 20 languages worldwide.

His great talent brought him very close to many leaders of his time, whom he extolled in return for money and gifts. His political ambitions, however, ultimately soured his relations with his patrons and his egomania may have cost him his life when the subjects of some of his verse attacked him.

Childhood and youth

Al-Mutanabbi was born in the Iraqi city of Kufah in 915. His father claimed descent from the South Arabian tribe of Banu Ju'fa.[4] His last name, Al-Kindī, was attributed to the district he was born.[5]

Owing to his poetic talent, and claiming predecession of prophet Saleh, al-Mutanabbi received an education in Damascus, Syria. When Shi'ite Qarmatians sacked Kufah in 924, he joined them and lived among the Banu Kalb and other Bedouin tribes. Learning their doctrines and dialect, he had many followers, and even claimed to be a Nabi (نَـبِي, Prophet)—hence the name Al-Mutanabbi ("The Would-be Prophet").

He led a Qarmatian revolt in Syria in 932. After its suppression and two years of imprisonment by the Ikhshid governor of Hims,[6] he recanted in 935 and became a wandering poet. During this period he began writing his first known poems. Political ambition to be a Wali led al-Mutanabbi to the courts of Sayf al-Dawla and Abu al-Misk Kafur but in this ambition he failed.

Al-Mutanabbi and Sayf al-Dawla

Al-Mutanabbi lived at the time when the Abbasid Caliphate started coming apart and many of the states in the Islamic world became politically and militarily independent. Chief among those states was the Emirate of Aleppo.

He began to write panegyrics in the tradition established by the poets Abu Tammam and al-Buhturi. In 948 he joined the court of Sayf al-Dawla, the Hamdanid poet-prince of northern Syria. Sayf al-Dawla was greatly concerned with fighting the Byzantine Empire in Asia minor, where Al-Mutanabbi fought alongside him. During his nine years stay at Sayf al-Dawla's court, Al-Mutanabbi wrote his greatest and most famous poems, panegyrics in praise of his patron that rank as masterpieces of Arabic poetry.

During his stay in Aleppo, Al-Mutanabbi found himself at odds with many scholars and poets in Sayf al-Dawla's court, including Abu Firas al-Hamdani, a poet and Sayf al-Dawla's cousin. In addition, Al-Mutanabbi lost Sayf al-Dawla's favor because of his political ambition to be Wāli. The latter part of this period was clouded with intrigues and jealousies that culminated in al-Mutanabbi's leaving Syria for Egypt, then ruled in name by the Ikhshidids.

Al-Mutanabbi in Egypt

Al-Mutanabbi joined the court of Abu al-Misk Kafur after parting ways with Saif al Dawla. Kafur mistrusted Al-Mutanabbi's intentions, claiming them to be a threat to his position. Al-Mutanabbi realized that his hopes of becoming a statesman were not going to bear fruit and he left Egypt in c. 960. After he left, he heavily criticized Abu al-Misk Kafur with satirical odes.

Poetry and famous sayings

Mutanabbi's egomaniacal nature seems to have got him in trouble several times and might be why he was killed. This can be seen in his poetry, which is often conceited:

- In a famous poem he speaks to the power of identity and the freedom that comes with knowing oneself.

| و أسمعت كلماتي من به صمم | أنا الذي نظر الأعمى إلى أدبي | |

| والسيف والرمح والقرطاس والقلم | الخيل والليل والبيداء تعرفني |

| ʾAnā l-ladhī naẓara l-ʾaʿmā ʾilā ʾadab-ī | Wa-ʾasmaʿat kalimāt-ī man bi-hī ṣamamu | |

| Al-ḫaylu wa-l-laylu wa-l-baydāʾu taʿrifu-nī | Wa-s-saifu wa-r-rumḥu wa-l-qirṭāsu wa-l-qalamu. |

| I am the one whose literature can be seen (even) by the blind | And whose words are heard (even) by the deaf. | |

| The steed, the night and the desert all know me | As do the sword, the spear, the scripture and the pen. |

- He was also known to have said:

| فلا تظنن أن الليث يبتسم | إذا رأيت نيوب الليث بارزة |

| If you see the lion's canines | Do not think that the lion is smiling. | |

| تجري الرياح بما لا تشتهي السفن | ما كل ما يتمنى المرء يدركه |

| Not all one hopes achieves | Winds blow counter to what ships desire. | |

| فَلا تَقنَعْ بما دونَ النّجومِ | إذا غامَرْتَ في شَرَفٍ مَرُومِ |

| If you ventured in pursuit of glory | Don't be satisfied with less than the stars.[n 1] | |

Death

In 957 Mutanabbi left Aleppo, making his way to Egypt and the court of the Abu al-Misk Kafur. In 960 the poet left Egypt, penning several satires about Kafur. He traveled to Baghdad but was killed resisting thieves before reaching the city.[8]

Legacy

Ibn Jinni the grammarian (c. 941/2—1001/2) wrote a commentary on al-Mutanabbi's poetry titled Al-Fasr ('The Explanation').[n 2][9] The poet philosopher Abu Al Alaa al-Marri has also written a book of exegesis on Al-Mutanabbi's poetry.[10] Al Marri, himself an accomplished poet, would usually refer to al-Mutanabbi affectionately as "our poet". Encyclopedia Britannica states: "He gave to the traditional qaṣīdah, or ode, a freer and more personal development, writing in what can be called a neoclassical style that combined some elements of Iraqi and Syrian stylistics with classical features."[11]

Al-Mutanabbi Street

In 1932, Mutanabbi Street, a bookselling street market of Baghdad, was named after al-Mutanabbi to honor him who, at the time, was very well-known in the region. The narrow car-free street is full of booksellers and book stores and it's one kilometer long. At the entrance of the street is an arch adorned with the poet’s quotes and on the end of it is a statue of al-Mutanabbi that overlooks the Tigris River. Over time, al-Mutanabbi Street evolved into a symbol of intellectual freedom, attracting writers, artists, and diverse dissenting voices from across the country.[12][13]

Notes

- NASA mentioned this saying, as they congratulated the United Arab Emirates for the Emirates Mars Mission.[7]

- Only in the MS of Al-Fihrist in the Chester Beatty Library.

References

- Nadīm (al-) 1970, p. 373.

- Nadīm (al-) 1970, p. 1066.

- Khallikān (Ibn) 1843, pp. 102–110, I.

- Hámori, András P. "al-Mutanabbī". Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE.

- al-Mutanabī. (2005). Diwān al-Mutanabī. Bayrūt: Dār al-Jīl. ISBN 9953-78-127-3. OCLC 225423623.

- Khallikān (Ibn) 1843, p. 104, I.

- @NASAPersevere (9 February 2021). "Dear @HopeMarsMission, congratulations on arriving at Mars! In the words of the poet Al Mutanabbi" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Arberry, Arthur (1967). Poems of Al-Mutanabbi: A Selection with Introduction, Translations and Notes (1st ed.). London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–116. ISBN 978-0521108485.

- Nadīm (al-) 1970, p. 189.

- ""معجز أحمد": كيف نظر المعري إلى المتنبي". alaraby.co.uk.

- "Al-Mutanabbī | Muslim poet | Britannica".

- Travers, Alannah. "Mutanabbi Street: An intellectual haven overcomes Iraq's pain". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- "Baghdad rediscovers Al-Mutanabbi Street after renovation |". AW. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

Bibliography

- Owles, Eric (18 December 2008). "Then and Now: A New Chapter for Baghdad Book Market". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 74.

- Al-Mutanabbî, Le Livre des Sabres, choix de poèmes, présentation et traduction de Hoa Hoï Vuong & Patrick Mégarbané, Actes Sud, Sindbad, novembre 2012.

- Arberry, A. J. (trans.), Poems of al-Mutanabbi: A Selection with Introduction, Translations and Notes (London: Cambridge University Press, 1967).

- Khallikān (Ibn), Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad (1843). Wafayāt al-A'yān wa-Anbā' Abnā' al-Zamān (The Obituaries of Eminent Men). Vol. I. Translated by McGuckin de Slane, William. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. pp. 102–110.

- Nadīm (al-), Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq Abū Ya'qūb al-Warrāq (1970). Dodge, Bayard (ed.). The Fihrist of al-Nadim; a tenth-century survey of Muslim culture. New York & London: Columbia University Press. pp. 189, 373, 1066.

- Nadīm (al-), Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq (1872). Flügel, Gustav (ed.). Kitāb al-Fihrist (in Arabic). Leipzig: F.C.W. Vogel. p. 552 (169).

- Thaʻālibī, ʻAbd al-Mālik b. Muḥ. (1847). Dieterici, Friedrich (ed.). Mutanabbi und Seifuddaula aus der Edelperle [Yatîmat al-dahr] des Tsaâlibi (in German and Arabic). Leipzig: Fr. Chr. Wilh. Vogel.

- Warren, James (trans.), The Complete Poems of Al-Mutanabbi, (Cultural Books, 2022) ISBN 9798218064082

- Wormhoudt, Arthur (trans.), The Diwan of Abu Tayyib Ahmad Ibn Al-Husayn Al-Mutanabbi (Kazi 2002) ISBN 9781930637382