Agnes of Courtenay

Agnes of Courtenay (c. 1136 – c. 1184) was a Frankish noblewoman who held considerable influence in the Kingdom of Jerusalem during the reign of her son, King Baldwin IV.

| Agnes of Courtenay | |

|---|---|

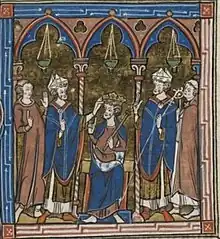

The annulment of the marriage of Agnes and Amalric | |

| Born | c. 1136 |

| Died | c. 1184 |

| Spouse | Reynald of Marash Amalric of Jerusalem Hugh of Ibelin Reginald of Sidon |

| Issue | Baldwin IV of Jerusalem Sibylla of Jerusalem |

| House | House of Courtenay |

| Father | Joscelin II of Courtenay |

| Mother | Beatrice of Saone |

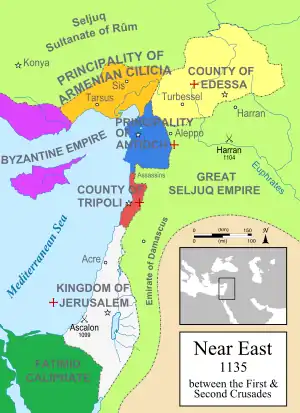

Agnes was a teenager when her first husband, Reynald of Marash, died in a 1150 battle with the Turks, who conquered the County of Edessa from her parents, Joscelin II of Edessa and Beatrice of Saone, the next year. As an impoverished young widow she married Amalric, the younger brother of King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. When Amalric unexpectedly inherited the crown in 1163, the High Court of Jerusalem refused to accept Agnes as queen and insisted that Amalric repudiate her in return for their recognition of his succession. Agnes contracted two further advantageous marriages, to powerful noblemen Hugh of Ibelin and Reginald of Sidon successively.

Agnes's influence grew rapidly after Amalric died in 1174 and their son, Baldwin IV, became king. Despite having been separated from him since his infancy, she became her son's trusted advisor. It became clear soon after his accession that he suffered from leprosy, which precluded him from fathering children. Agnes selected government officials and influenced succession by choosing husbands for both Sibylla, her daughter by Amalric, and Isabella, Amalric's daughter by his second wife, Maria Comnena. She advised Baldwin IV to have Sibylla marry Guy of Lusignan, who thus became the king-in-waiting, and when Baldwin decided to disinherit Guy, Agnes convinced him and the nobility to crown Sibylla's son, Baldwin V, instead.

Count Raymond III of Tripoli and the brothers Balian (second husband of Maria) and Baldwin of Ibelin were Agnes's chief contenders for power, and it is from sources close to them that nearly all information about Agnes is derived. She has consequently usually been criticized by historians as self-seeking, unscrupulous, and morally loose.

Early life

Agnes was born between 1134 and 1137. She hailed from the junior branch of the House of Courtenay. Her father, Count Joscelin II of Edessa, was the second cousin of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem, Princess Alice of Antioch, and Countess Hodierna of Tripoli, connecting her to all the Frankish Catholic rulers of the Latin East. Beatrice, her mother, held estates at Saone (in the Principality of Antioch) in dower as the widow of William of Zardana.[1]

Agnes's first marriage, to Reynald of Marash, ended in his death at the Battle of Inab in 1149. They had had no children. Agnes enjoyed dower rights in Marash until the town was conquered by the Muslim Turks a few months later.[1] They captured her father the following year and kept him in prison. Her mother found herself unable to defend the remnants of the County of Edessa and sold them to the Byzantine emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, for an annual pension to be paid to herself and her children, Agnes and Joscelin III. The mother and children then retired to Saone.[1]

Royal marriage

In 1157, Agnes came to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, where she married Queen Melisende's younger son, Amalric, the count of Jaffa and Ascalon,[1] and became a countess.[2] Though she was penniless, Agnes was the most suitable bride for Amalric due to her high birth.[3] Yet the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Fulk, objected to the marriage. According to William of Tyre, Fulk was upset by the couple's kinship, while the 13th-century Lignages d'Outremer states that Agnes had been betrothed to the lord of Ramla, Hugh of Ibelin, and that Amalric married her when she came to marry Hugh, irritating the patriarch.[4] Agnes and Amalric had a daughter, Sibylla, and then, in 1161, a son, Baldwin.[3]

Upon the death of his brother, King Baldwin III, on 10 February 1163, Amalric stood to succeed to the throne of Jerusalem. Yet the High Court refused to recognize him as king unless he separated from Agnes. The reason for this unusual request is unclear because all the primary sources, including William of Tyre, are hostile to Agnes.[3] Reasons proposed by scholars include a tarnished reputation of Agnes[5] and fear of the barons that Agnes would bestow royal favor on the landless exiles from Edessa if she became queen.[6] The barons may also have believed Agnes, like her mother-in-law, would wield power in the government or that Amalric could make a politically and financially better match; if so, they were to be proven right on both counts.[7]

Amalric gave in to the barons' demand; his and Agnes's marriage was annulled on the grounds of consanguinity. The couple appear to have proved that their marriage had been contracted in good faith for the ecclesiastical court granted Amalric's request that their children, Sibylla and Baldwin, be legitimized, and that Agnes be absolved of any moral condemnation.[6] Agnes was consequently never queen.[7] She received no settlement but retained the prestigious title of countess, unique in the kingdom, for the rest of her life.[2]

Remarriages

Immediately after the annulment of the royal marriage, Agnes married Hugh of Ibelin, to whom she may have been engaged before meeting Amalric.[2] Agnes's ability to nearly instantly contract such an advantageous marriage suggests that the High Court did not refuse to recognize her as queen due to a moral scandal.[8] This marriage was likely arranged by Amalric, who benefited from no longer having to pay for his former wife's upkeep.[7] Agnes had little contact with her children after her separation from Amalric.[9] Agnes's son, Baldwin, was aged two and grew up not knowing her; they probably only saw each other on public occasions.[2] Amalric only remarried in 1167, taking the Byzantine emperor's grandniece Maria Comnena as his second wife.[10]

Hugh died in c. 1169. Agnes then married her fourth and final husband, Reginald Grenier, who in 1071 succeeded his father, Gerard Grenier, as the lord of Sidon.[11] The long-standing belief that Agnes and Reginald's marriage was dissolved at Gerard's request, and then presumably revalidated after Gerard's death, stems from the misunderstanding of Gerard's testimonial role in the dissolution of Agnes's marriage to Amalric.[12]

Son's accession

King Amalric died on 11 June 1174.[13] Though he had been showing symptoms of leprosy, the High Court agreed that there was no better candidate for new king than Agnes and Amalric's son, Baldwin IV.[14] Being a minor, Baldwin needed a regent to rule on his behalf. The custom that the mother of the minor heir should govern on his or her behalf could not be applied in Baldwin's case: his mother, Agnes, was not the previous king's widow, while the previous king's widow, Queen Maria, was not the new king's mother. The High Court's ruling on that occasion that the right to regency belonged to the "nearest relation, male or female, on the mother’s side if the claim to the throne comes through the mother, or the nearest male relation on the father’s side if the claim to the throne comes through him" was entrenched into the law of the kingdom. Eventually it was Amalric's closest male kinsman, Count Raymond III of Tripoli, who claimed the regency.[15]

Agnes returned to the royal court when Raymond became regent. This was probably requested by her husband, Reginald of Sidon, and Baldwin and Balian of Ibelin, brothers of her previous husband, Hugh, in return for their support of Raymond's regency. As the queen dowager, Maria, retired to her dower city of Nablus, Agnes's arrival at the court made her the queen mother in practice even if she was just a countess in title.[16] She had to build a bond with an adolescent son who hardly knew her and though a great mutual affection developed between them, the relationship was likely more akin to that of aunt and nephew than to that of mother and son. The young king was certainly glad to have her back in his life and in charge of his household. Raymond willingly shared the royal task of church patronage with Agnes: Raymond made William of Tyre the new archbishop of Tyre in 1174, while Agnes secured the appointment of Heraclius of Jerusalem to the archbishopric of Caesarea.[17] Ernoul, a protegé of Amalric's second wife, Queen Maria,[16] accuses Agnes of love affairs with Heraclius[17] and Aimery of Lusignan, who was also on a steady rise to the highest position in the kingdom.[18]

Courtenay ascendancy

In 1175, Agnes raised the funds to pay the ransom for her brother, Joscelin, who had been imprisoned by the Turks in Aleppo since 1164. The sum of 50,000 dinars, which Agnes could not have afforded, must have come from the royal treasury and with the approval of the regent, Raymond.[19] The following year, after Baldwin reached the age of majority and Raymond's regency ended, Agnes influenced Baldwin to name Joscelin to the vacant government post of seneschal. Joscelin, an uncle with no claim to the throne, was a prudent choice and proved both markedly competent and wholly loyal to the king.[20]

Royal matchmaking

Agnes came to strongly influence her daughter, Sibylla, as well.[21] As it became apparent that Baldwin was indeed affected by leprosy and precluded from marrying and siring children,[22] Sibylla's marriage became a central question to the royal government.[23] Sibylla's first husband, William Longsword of Montferrat, died in 1177.[24] In 1180, under unclear circumstances, Sibylla, by then the countess of Jaffa and Ascalon in her own right, married Guy of Lusignan, brother of Aimery. She was supposed to marry Duke Hugh III of Burgundy but, according to Ernoul, promised her hand to Baldwin of Ibelin on the condition that he paid his debt to the Muslim ruler of Egypt, Saladin. While Baldwin of Ibelin was in Constantinople procuring Emperor Manuel's help in raising these funds, Ernoul elaborates, Sibylla and Agnes were convinced by Aimery that the princess should marry his brother Guy instead.[25] This account is rejected as romanticized Ibelin propaganda by historian Bernard Hamilton, who argues that neither Sibylla nor Agnes would have acted so foolishly.[26] William of Tyre, on the other hand, tells about a coup attempt launched by Count Raymond III of Tripoli and Prince Bohemond III of Antioch; they likely intended to depose Baldwin IV, install Sibylla, and have her marry a man of their own choosing (probably Baldwin of Ibelin), thereby removing the Courtenays from power.[27] The king, acting on his mother's advice,[28] foiled the coup by having Sibylla marry Guy.[29]

From 1180 to 1181, Joscelin was on a diplomatic mission in Constantinople, leaving King Baldwin to conduct government alone. The young monarch's health was deteriorating, however, and during this time he particularly relied on his mother, Agnes.[30] She accompanied him on campaigns and attended High Court meetings over which he presided.[17] In October 1180, Baldwin had his younger half-sister, Isabella, daughter of Amalric by Maria Comnena, betrothed to Humphrey IV of Toron.[28] This match too was almost certainly Agnes's idea for she was the immediate beneficiary: the marriage contracted stipulated that Humphrey should give up his patrimonial fiefs of Toron and Chastel Neuf, which Baldwin gave to Agnes. For the first time, Agnes was a great landowner in her own right.[28] Balian, who had married Isabella's mother, Queen Maria, and his brother Baldwin of Ibelin were also prevented from using the young princess to conspire against Agnes's children.[31]

Height of power

Agnes was at the height of her power during Baldwin IV's personal rule.[32] Raymond and the Ibelins were in no position to challenge the countess and her party: her husband ruled Sidon; her son held the great royal cities of Jerusalem, Tyre, and Acre; her daughter and son-in-law ruled the county of Jaffa and Ascalon; her supporter Raynald of Châtillon was lord of Oultrejordain and Hebron; and she was newly landed herself. In 1182, Raymond found that her influence was such that she was able to refuse him entry into the kingdom. Agnes won another victory the same month when Agnes persuaded her son to select Heraclius over William to become the new Latin patriarch of Jerusalem.[32]

Baldwin IV was becoming weaker, however, and in 1183 appointed Sibylla's husband, Guy, to rule as regent. Agnes was not threatened because she held sway over Sibylla and Guy owed his position to Agnes.[32] Baldwin, who was by then blind[33] and crippled,[34] became disillusioned with Guy's character and capability and decided to depose him from the regency in late 1183 at a council convened to deal with Saladin's siege of Kerak, where Isabella was marrying Humphrey.[35] The council was attended by Guy, Raymond of Tripoli, Bohemond of Antioch, Reginald of Sidon, the Ibelin brothers, and Agnes.[36] This presented an opportunity to the countess's opponents: if Guy was to be excluded from regency, the next best candidate was her enemy, the count of Tripoli. Agnes, exhibiting remarkable composure, offered a compromise solution which the assembled nobility accepted: the king should rule personally rather than appoint a regent (thus guaranteeing the continuing of the influence of Agnes and her party) but should also designate an heir to exclude Guy from kingship.[35] The champions of Sibylla's claim, Raynald and Joscelin, were defending Kerak; and Isabella's claim could not be entertained as she was besieged in Kerak.[36] Raymond may have hoped to present himself as the suitable heir;[36] if so, the countess thwarted his plan by proposing her grandson, Baldwin V, Sibylla's son by her first husband, William of Montferrat, and the boy was duly crowned.[35] The countess was unable to prevent her son from further going after Guy nor did she intervene in the king's attempt to separate Guy from Sibylla in early 1184.[37]

Death

The last source to mention Countess Agnes as living is Ibn Jubayr,[38] who passed by Toron in September 1184 and remarked, in the language commonly used by Muslims of the time when referring to Christians, that the area "belongs to the sow known as queen who is the mother of the pig who is lord of Acre–may God destroy it".[37] Historian Hans Eberhard Mayer argues that Agnes died before 1 February 1185 because she took no part in the selection of regent for Baldwin V.[38] Baldwin IV died soon after, leaving Baldwin V as the sole king and Raymond as regent once again. If she was still alive, Agnes's influence diminished but did not end, as the boy king was under the guardianship of her brother, Joscelin. Baldwin V's death in mid-1186 caused a succession crisis in which Agnes played no part; on 21 October, Guy, now king after all, acknowledged that Joscelin had satisfactorily executed his sister's last will.[37]

Appearance and character

Judging by her ability to make excellent matches for herself while virtually impoverished, historian Bernard Hamilton surmises that Agnes must have been attractive. He similarly concludes that the resentment she caused among her peers points to a force of her character.[16] In her rise from a powerless repudiated wife to the person who arranged marriages for both of Amalric's daughters and who appointed chief officeholders in the kingdom he sees evidence of "clearly a remarkably clever woman".[32]

The "bad press" she received during her lifetime has led to historians traditionally describing her as unscrupulous and opportunistic. The view that she exploited her son's illness to fill the court with corrupt officials at the expense of capable men comes from William of Tyre, who never forgave her for her role in his defeat in the patriarchal election; he calls her a "woman who was relentless in her acquisitiveness and truly hateful to God".[16] Ernoul, whose information about Agnes is derived from her husband's second wife, Maria, is likewise very hostile and portrays her as a woman of loose morals.[16] Hamilton argues that Agnes's kindness and devotion to her sick son would have earned her praise from less hostile witnesses.[17]

Hamilton judges Agnes as a "worthy daughter-in-law of Queen Melisende", if not as pious, and argues that Agnes had a more pronounced influence on the history of the Jerusalem-centred kingdom than any woman other than Melisende.[37]

References

- Hamilton 2000, p. 24.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 26.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 159.

- Hamilton 2005, p. 24.

- Hamilton 2005, p. 25.

- Hamilton 2005, p. 26.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 160.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 25.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 164.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 161.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 34.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 35.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 32.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 41.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 88-89.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 95.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 96.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 97.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 104.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 105-106.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 165.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 109.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 101.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 139.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 152.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 153.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 154.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 167.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 155.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 160.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 161.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 168.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 253.

- Hamilton 2000, pp. 187, 240.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 169.

- Hamilton 2000, pp. 194.

- Hamilton 1978, p. 170.

- Hamilton 2000, p. 214.

Sources

- Hamilton, Bernard (1978). "Women in the Crusader States: The Queens of Jerusalem". In Derek Baker (ed.). Medieval Women. Ecclesiastical History Society.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2000). The Leper King and his Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press.

- Hans Eberhard Mayer, "The Beginnings of King Amalric of Jerusalem", in B. Z. Kedar (ed.), The Horns of Hattin, Jerusalem, 1992, pp. 121–35.

- Marie-Adélaïde Nielen (ed.), Lignages d'Outremer. Paris, 2003.

- William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. E. A. Babcock and A. C. Krey, trans. Columbia University Press, 1943.

- Reinhold Röhricht (ed.), Regesta Regni Hierosolymitani MXCVII-MCCXCI, and Additamentum, Berlin, 1893–1904.

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, vol. II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press, 1952.