Takeo Kurita

Takeo Kurita (Japanese: 栗田 健男, Hepburn: Kurita Takeo, 28 April 1889 – 19 December 1977) was a vice admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during World War II. Kurita commanded IJN 2nd Fleet, the main Japanese attack force during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle in history.

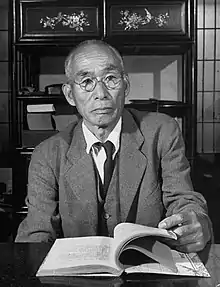

Takeo Kurita | |

|---|---|

Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita (1942–45) | |

| Born | 28 April 1889 Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan |

| Died | 19 December 1977 (aged 88)[1] Nishinomiya, Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1910–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Order of the Sacred Treasure (2nd class) |

Biography

Early life

Takeo Kurita was born in Mito city, Ibaraki Prefecture, in 1889. He was sent off to Etajima in 1905 and graduated from the 38th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1910, ranked 28th out of a class of 149 cadets. As a midshipman, he served on the cruisers Kasagi and Niitaka. On being commissioned as ensign in 1911, he was assigned to Tatsuta.

After his promotion to sub-lieutenant in 1913, Kurita served on the battleship Satsuma, destroyer Sakaki and cruiser Iwate. Kurita became a lieutenant on 1 December 1916, and served on a number of ships: protected cruiser Tone, destroyers Kaba and Minekaze. He also served as either the chief torpedo officer or executive officer on Minekaze, Yakaze, and Hakaze. In 1920, he was given his first command: the destroyer Shigure. In 1921, he assumed command of Oite.[1]

Promoted to lieutenant commander in 1922, Kurita captained the destroyers Wakatake, Hagi, and Hamakaze. As commander from 1927, he commanded the destroyer Urakaze, 25th Destroyer Group and 10th Destroyer Group.[1]

As captain from 1932, he commanded the 12th Destroyer Group, the cruiser Abukuma, and from 1937 the battleship Kongō.[1]

Kurita became a rear admiral on November 15, 1938, commanding the 1st Destroyer Flotilla then the 4th Destroyer Flotilla.[1] He was in command of the 7th Cruiser Division at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor.[2]

Early campaigns

Kurita's 7th Cruiser Division participated in the invasion of Java in the Dutch East Indies in December 1941, and in the Indian Ocean Raid where he led a fleet of six heavy cruisers and the light carrier Ryūjō that sank 135,000 tons of shipping in the Bay of Bengal.[2] During the Battle of Midway (serving under Nobutake Kondō), he lost the cruiser Mikuma. Kurita was promoted to vice admiral on 1 May 1942, and was reassigned to the 3rd Battleship Division in July.

In the Guadalcanal Campaign, Kurita led his battleships in an intense bombardment of Henderson Field on the night of 13 October, firing 918 heavy high explosive shells at the American airfield. This was the single most successful Japanese attempt to incapacitate Henderson Field by naval bombardment and allowed a large transport convoy to resupply forces on Guadalcanal the next day relatively unmolested. Kurita later commanded major naval forces during the Central Solomon Islands campaign and during the Battle of the Philippine Sea. In 1943, Kurita replaced Admiral Kondō as the commander of IJN 2nd Fleet.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

It was as Commander-in-Chief of the IJN 2nd Fleet dubbed "Center Force" during the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea and the Battle off Samar (both part of the Battle of Leyte Gulf) for which Kurita is best known. The IJN 2nd Fleet included the largest and most heavily armed battleships in the world, Yamato and Musashi. Additionally, the IJN 2nd Fleet included the older battleships Nagato, Kongō, and Haruna, 10 cruisers and 13 destroyers. Critically, however, the IJN Second Fleet did not include any aircraft carriers.

Kurita was a dedicated officer, willing to die if necessary, but not wishing to die in vain. Like Isoroku Yamamoto, Kurita believed that for a captain to "go down with his ship" was a wasteful loss of valuable naval experience and leadership. When ordered by Admiral Soemu Toyoda to take his fleet through the San Bernardino Strait in the central Philippines and attack the American landings at Leyte, Kurita thought the effort a waste of ships and lives, especially since he could not get his fleet to Leyte Gulf until five days after the landings, leaving little more than empty transports for his huge battleships to attack. He bitterly resented his superiors, who, while safe in bunkers in Tokyo, ordered him to fight to the death against hopeless odds and without air cover. For his part, Toyoda was aware that the plan was a major gamble, but as the Imperial Japanese Navy fleet was running out of fuel and other critical supplies, he felt that the potential gain offset the risk of losing a fleet that was about to become useless in any event.

1. Ambush in the Palawan Passage

While his fleet was en route from Brunei to attack the American invasion fleet, Kurita's ships were attacked in the Palawan Passage by U.S. submarines. USS Darter damaged the heavy cruiser Takao and sank Kurita's flagship, the heavy cruiser Atago, forcing him to swim for his life while USS Dace sank the heavy cruiser Maya. Kurita was plucked from the water by a destroyer and transferred his flag to the Yamato, but Kurita's dunking did him little good, especially since he had only recently recovered from a severe case of dengue fever, and no doubt contributed to the fatigue which may have influenced his subsequent actions.[3]

2. Battle of the Sibuyan Sea

While in the confines of the Sibuyan Sea and approaching the San Bernardino Strait, Kurita's force underwent five aerial attacks by U.S. carrier planes which damaged several of his ships, including Yamato.[4] Constant air attacks from Admiral William "Bull" Halsey's 3rd Fleet scored two bomb hits on Yamato, reducing her speed, and numerous torpedo and bomb hits on Musashi, mortally wounding her. They also scored a number of damaging near misses on other vessels, reducing fleet speed to 18 knots.[5] Knowing that he was already six hours behind schedule and facing the possibility of a sixth attack in the narrow confines of the San Bernardino Strait, Kurita requested air support and turned his fleet west away from Leyte Gulf.[6]

Thus began a chain of events that continues to engage historians and biographers to this day. Halsey, believing that he had mauled Kurita's fleet and that the Japanese Center Force was retreating, and believing that he had the orders and authorization to do so, abandoned his station guarding General MacArthur's landing at Leyte Gulf and the San Bernardino Strait, in order to pursue Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa's Northern Fleet of Japanese carriers that were sent as a decoy to lure the Americans away from Leyte. But before doing so, in fact before Ozawa's force had been sighted, Halsey had sent a message announcing a "battle plan" to detach his battleships to cover the exit of the strait. With the decision to attack Ozawa, this battle plan was never executed and the heavy ships went north with the carriers. The battle plan called for detaching the battleships to guard San Bernardino Strait, which meant that Halsey's flagship, the battleship USS New Jersey, would have been detached too, leaving him behind while Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher chased the carriers. Unfortunately for Halsey, after an hour and a half without further air attacks Kurita turned east again at 1715 towards San Bernardino Strait and the eventual encounter with Kinkaid's forces in Leyte Gulf.[7]

3. Battle off Samar

Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander 7th Fleet and responsible for protecting the landing forces, assumed that Halsey's "battle plan" was a deployment order and that Task Force 34 (TF 34) was actually guarding San Bernardino Strait. Kinkaid thus concentrated his battleships to the south in order to face the Japanese "Southern Force". During the night of 24–25 October 1944, Kurita changed his mind again, and turned his ships around and headed east again, toward Leyte Gulf. On the morning of 25 October, Kurita's fleet, led by Yamato, exited San Bernardino Strait and sailed south along the coast of Samar. Thirty minutes after dawn, the battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy sighted "Taffy 3" — a task unit of Kinkaid's covering forces that consisted of six escort carriers, three destroyers and four destroyer escorts, commanded by Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague. Taffy 3 was intended to provide shore support and anti-submarine patrols, not to engage in fleet action against battleships.

Believing he had chanced upon the carriers of the American 3rd Fleet, Kurita immediately ordered his battleships to open fire. Recognizing that his best chance depended upon destroying the aircraft carriers before they could launch their aircraft, Kurita gave the order for "general attack" rather than take the time to reform his ships for action with the enemy. Kurita then compounded his error by ordering his destroyers to the rear to prevent them from obstructing his battleships' line of fire, preventing them from racing ahead to cut off the slower American carriers. Concern that his destroyers would burn too much fuel in a flank speed stern chase of what Kurita presumed were 30-knot fleet carriers also played a part in Kurita's decision.[8] However, at the moment Taffy 3 was sighted, Center Force was in the midst of changing from nighttime scouting to daytime air defense steaming formation. Kurita's ships thus charged uncoordinated into action and Kurita quickly lost tactical control of the battle, a situation not helped by poor visibility, intermittent rain squalls and a wind direction favorable to the Americans, who immediately began to make smoke for additional concealment.

Kurita's forces mauled Taffy 3, sinking the escort carrier Gambier Bay, the destroyers Hoel and Johnston, and the destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts, and inflicting significant damage on most of the other ships. But continual air attacks by aircraft from Taffy 3 and Taffy 2 stationed farther south and a determined counterattack by the U.S. escorts served to further confuse and separate Kurita's forces. Kurita, whose flagship Yamato fell far behind early in the battle while avoiding a torpedo salvo from USS Hoel, lost sight of the enemy and many of his own ships. Meanwhile, the courageous efforts of the Taffies had cost him three heavy cruisers: Chikuma, Suzuya, and Chōkai. Many of his other ships had also been hit and most had suffered casualties from the relentless strafing. After about two and a half hours in action with Taffy 3, Kurita ordered his force to regroup on a northerly course, away from Leyte.

By this time, Kurita had received news that the Japanese Southern Force, which was to attack Leyte Gulf from the south, had already been destroyed by Kinkaid's battleships. With Musashi gone, Kurita still had four battleships but only three cruisers remaining, all of his ships were low on fuel and most of them were damaged. Kurita was intercepting messages that indicated Admiral Halsey had sunk all four carriers of the "Northern Force" and was racing back to Leyte with his battleships to confront the Japanese fleet, and that powerful elements of 7th Fleet were approaching from Leyte Gulf. After steaming back and forth off Samar for two more hours, Kurita, who had been on Yamato's bridge for nearly 48 hours by this point, and his chief of staff Tomiji Koyanagi decided to retire and retreated back through the San Bernardino Strait.

Kurita's ships were subjected to further air attack the rest of the day and Halsey's battleships just missed catching him that night, sinking the destroyer Nowaki, which had remained behind to save the survivors from Chikuma. Kurita's retreat saved Yamato and the remainder of the IJN 2nd Fleet from certain destruction, but he had failed to complete his mission, attacking the amphibious forces in Leyte Gulf. The path had been laid open to him by the sacrifices of the Northern and Southern Forces, but closed again by the determination and courage of the Taffies.

After Leyte and postwar

Kurita was criticized by some elements in the Japanese military for not fighting to the death. In December, Kurita was removed from command. In order to protect him against assassination, he was reassigned as commandant of the Imperial Japanese Navy Academy.[9][10]

Following the Japanese surrender, Kurita found work as a scrivener and masseur, living quietly with his daughter and her family. He was found by an American naval officer after the war where he was interviewed for the Analysis Division of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey.

With Kurita's address in hand, a young American naval officer got out of a jeep and spotted the unimposing figure tending to his garden chores. Years later, he still vividly recalled the moment: "It really made an impression of me. The war was just over. Less than a year before Kurita had been in command of the largest fleet that was ever put together, and there he was out there chopping potatoes."[11]

Kurita never discussed politics or the war with his family or others, except to conduct a brief interview with a journalist, Masanori Itō, in 1954 when he stated that he had made a mistake at Leyte by turning away and not continuing with the battle, a statement he later retracted. In retirement, Kurita made twice-yearly pilgrimages to Yasukuni Shrine to pray for his dead comrades-in-arms. In 1966, he was present at the deathbed of his old colleague, Jisaburō Ozawa, at which he silently wept.

It was not until he was in his 80s that Kurita began to again speak of his actions at Leyte. He claimed privately to a former Naval Academy student (and biographer), Jiro Ooka, that he withdrew the fleet from the battle because he did not believe in wasting the lives of his men in a futile effort, having long since believed that the war was lost.[12]

Kurita died in 1977 at age 88, and his grave is at the Tama Cemetery in Fuchu, Tokyo.

Notes

- Nishida, Hiroshi. "Kurita Takeo". Imperial Japanese Navy. Archived from the original on 2014-03-14. Retrieved 2007-02-25.; Nishida, Hiroshi. "Offensive Forces". Imperial Japanese Navy. Archived from the original on 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Rear-Admiral Takeo Kurita". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- Ito, Masanori (1956). The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy. New York: W.W, Norton. p. 166.

- Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy, p.127.

- Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy, p.128.

- Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 129.

- Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy, p.132.

- Ito, The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy, p.172.

- Okumiya, Masatake (奥宮正武) (1987). "第四章 第三節 不当に批判されている人々 ― 南雲忠一中将、栗田健男中将 [Chapter 4 Section 3 Unfairly criticized people-Lieutenant General Chuichi Nagumo and Lieutenant General Takeo Kurita]". 太平洋戦争の本当の読み方 [The Real Reading of the Pacific War] (in Japanese). Tokyo: PHP Institute. p. 344. ISBN 4-569-22019-3.

- Takagi, Yukichi (高木惣吉) (1959). 太平洋海戦史 [Pacific Naval History] (in Japanese) (revised ed.). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-00-413135-9.

- Goralski 323

- Thomas, Evan (October 2004). "Understanding Kurita's 'Mysterious Retreat'" (PDF). Naval History. United States Naval Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

References

- Goralski, Robert and Russel W. Freeburg (1987). Oil & War: How the Deadly Struggle for Fuel in WWII Meant Victory or Defeat. William Morrow and Company. New York. ISBN 0-688-06115-X

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942".

- Nishida, Hiroshi (2002). "Kurita, Takeo". Imperial Japanese Navy. Archived from the original on 2014-03-14. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- Thomas, Evan (2006). Sea of Thunder: Four Commanders and the Last Great Naval Campaign 1941–1945. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5221-7.

Further reading

- Cutler, Thomas (2001). The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23–26 October 1944. Annapolis, Maryland, U.S.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-243-9.

- D'Albas, Andrieu (1965). Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Devin-Adair Pub. ISBN 0-8159-5302-X.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-097-1.

- Field, James A. (1947). The Japanese at Leyte Gulf;: The Sho operation. Princeton University Press. ASIN B0006AR6LA.

- Friedman, Kenneth (2001). Afternoon of the Rising Sun: The Battle of Leyte Gulf. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-756-7.

- Halsey, William Frederick (1983). The Battle for Leyte Gulf. U.S. Naval Institute ASIN B0006YBQU8

- Hornfischer, James D. (2004). The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-80257-7.

- Hoyt, Edwin P.; Thomas H Moorer (Introduction) (2003). The Men of the Gambier Bay: The Amazing True Story of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-643-6.

- Lacroix, Eric; Linton Wells (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (2001). Leyte: June 1944 – January 1945 (History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12. Castle Books; Reprint ISBN 0-7858-1313-6

- Potter, E. B. (2005). Admiral Arleigh Burke. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-692-5.

- Potter, E. B. (2003). Bull Halsey. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-691-7.

- Sears, David The Last Epic Naval Battle: Voices from Leyte Gulf. Praeger Publishers (2005) ISBN 0-275-98520-2

- Willmott, H. P. (2005). The Battle Of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34528-6.

- Woodward, C. Vann (1989). The Battle for Leyte Gulf (Naval Series). Battery Press ISBN 0-89839-134-2

Web

- U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey Pacific – Interrogations of Japanese officials A list of the U.S. Naval Interrogations of Japanese Officials, conducted after the war, with full texts of the interviews. A number of these interviews are available on line and provide interesting insight from the Japanese commanders, who, many for first time, are openly critical of the war and their superiors. Admiral Kurita and his role in the war is discussed in a number of different interrogations.

- Understanding Kurita's Mysterious Retreat by Evan Thomas