Acacia parramattensis

Acacia parramattensis, commonly known as Parramatta wattle, is a tree of the family Fabaceae native to the Blue Mountains and surrounding regions of New South Wales. It is a tall shrub or tree to about 15 m (49 ft) in height with phyllodes (flattened leaf stalks) instead of true leaves. These are finely divided bipinnate . The yellow flowers appear over summer. It generally grows in woodland or dry sclerophyll forest on alluvial or shale-based soils, generally with some clay content.

| Parramatta wattle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Caesalpinioideae |

| Clade: | Mimosoid clade |

| Genus: | Acacia |

| Species: | A. parramattensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Acacia parramattensis | |

| |

| Occurrence data from AVH | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Racosperma parramattense (Tindale) Pedley | |

A fast-growing plant, it regenerates after bushfire by seed or suckering and can quickly colonise disturbed areas. Likewise it adapts readily to cultivation and is used in revegetation projects.

Description

Growing with an upright habit, Acacia parramattensis is a tall shrub or tree ranging from 2 to 15 m (7 to 50 ft) in height with smooth bark that can be dark green, dark brown or black. The branchlets are more or less terete (round in cross-section), sometimes with ridges.[1] The tips of new growth are yellow and finely furry becoming smooth with age. The dark green and slightly rough leaves are joined to the stem by a 0.5–2 cm (1⁄4–3⁄4 in) long petiole and are finely divided or bipinnate—that is, each leaf has 3–16 pairs of 1.5–6 cm (1⁄2–2+1⁄4 in) long pinnae (leaflets) arising from it, and each of these pinnae has anywhere from 14 to 62 (most commonly 20 to 40) pairs of pinnules off it. Each pinnule is 2 to 7 (rarely 9) mm long and 0.5–1 mm wide and linear or cultrate in shape.[2]

The yellow flowers appear from November to February, occasionally as late as April.[3] The yellow flowers are spherical and measure 4–7.5 mm (0.16–0.30 in) in diameter. they are arranged in panicles or racemes, with 25 to 50 flowers occurring in each flower head.[1] Flowers are followed by the development of the flat grey-black seed pods. Rough and furry when young before losing their fur, they are 2.5–11 cm (1–4+1⁄4 in) long and 3.5–8 mm (1⁄8–3⁄8 in) wide and sub-moniliform—linear in shape and slightly swollen over the spaces where the seeds are.[2] The mature seeds are released over November to January.[3]

A. parramattensis tends to flower later in the year than the similar early green wattle (Acacia decurrens) and black wattle (A. mearnsii).[4]

Taxonomy

Australian botanist Mary Tindale of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney described Acacia parramattensis in 1962 from material she collected in 1960 from Hazelbrook in the Blue Mountains near Sydney.[5] Its name is derived from the locality of Parramatta, west of Sydney.[6] Common names include Sydney green wattle and Parramatta wattle.[5]

Queensland botanist Les Pedley reclassified the species as Racosperma parramattense in 2003, in his proposal to reclassify almost all Australian members of the genus into the new genus Racosperma,[7] however this name is treated as a synonym of its original name.[5] Along with other bipinnate wattles, Acacia parramattensis is classified in the section Botrycephalae within the subgenus Phyllodineae in the genus Acacia. An analysis of genomic and chloroplast DNA along with morphological characters found that the section is polyphyletic, though the close relationships of many species were unable to be resolved. Acacia parramattensis appears to be most closely related to A. olsenii.[8]

Distribution and habitat

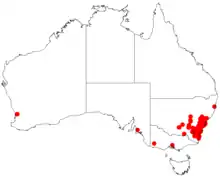

Acacia parramattensis is found in the Sydney Basin and Blue Mountains in central New South Wales, north to Yengo National Park,[1] west to Grenfell and south to Tumut,[2] from sea level to elevations of 900 metres (3,000 ft).[3] A component of dry sclerophyll forest or woodland, it is found in association with such trees as forest red gum (Eucalyptus tereticornis), Sydney blue gum (E. saligna), mountain white gum (E. dalrympleana), rough-barked apple (Angophora floribunda), turpentine (Syncarpia glomulifera), or in drier locations with gossamer wattle (Acacia floribunda), coast myall (A. binervia), or early green wattle (A. decurrens).[3] A. parramattensis is also a component of the rare and fragmented Southern Highlands Shale Woodlands community.[9]

Acacia parramattensis grows on alluvial or shale-based low- to medium-nutrient soil, often with some degree of clay content, or occasionally sandstone-based soils. It is found on lower slopes and along watercourses, as well as ridges. The annual rainfall is over 700 millimetres (28 in).[3] It has possibly naturalised in Tasmania and other parts of New South Wales.[2][10]

Ecology

The bark of A. parramattensis is thin and offers little protection from bushfire, with plants generally perishing from high intensity fires.[11] Most above-ground growth is killed by fire, though plants with trunks thicker than 10–15 cm (4–6 in) diameter at breast height (dbh) may resprout from epicormic buds.[3] Some plants can survive low intensity fires.[11] Acacia parramattensis has a suckering habit, and can grow from basal shoots after fire, though regeneration is generally by seed after severe fires. The seed has a hard coating and remains in the soil after dropping from the seedpods. It colonises disturbed areas, and the suckers can form groves of plants. The species has a juvenile period of around five years.[3]

The seed is consumed by the common bronzewing (Phaps chalcoptera).[3] The foliage serves as food for the caterpillars of the moonlight jewel (Hypochrysops delicia), imperial hairstreak (Jalmenus evagoras), amethyst hairstreak (Jalmenus icilius),[12] Adult imperial hairstreak also visit the plant.[13] The wood serves as food for larvae of the jewel beetle species Melobasis nitidiventris, Agrilus hypoleucus and A. australasiae.[14] Older trees that are infested by borers in turn attract the insectivorous yellow-tailed black cockatoo.[15] A. parramattensis is a host species for the mistletoe species Amyema cambagei and A. pendula.[16]

Cultural significance

In the Dharawal story of the Boo’kerrikin Sisters, one of the kindly sisters was turned into Acacia parramattensis. The other two sisters were turned into Acacia decurrens and Acacia parvipinnula.[17]

Cultivation

Acacia parramattensis is not commonly seen in cultivation though is grown locally in Sydney and the Blue Mountains.[6] Fast growing and adaptable, it grows 6 to 8 m (20 to 26 ft) high over five years.[3] It can provide shade in the garden, though is vulnerable to being infested by borers.[15] It is propagated by seed.[6]

Fieldwork conducted in the Southern Highlands found that the presence of bipinnate wattles (either as understory or tree) was related to reduced numbers of noisy miners, an aggressive species of bird that drives off small birds from gardens and bushland, and hence recommended the use of these plants in establishing green corridors and revegetation projects.[18]

References

- Harden, Gwen J. (1990). "Acacia parramattensis Tindale". Plantnet – New South Wales Flora Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Kodela, Phillip G. (2001). "Acacia". In Wilson, Annette; Orchard, Anthony E. (eds.). Flora of Australia. Vol. 11A, 11B, Part 1: Mimosaceae, Acacia. CSIRO Publishing / Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 237–38. ISBN 978-0-643-06718-9.

- Benson, Doug; McDougall, Lyn (1996). "Ecology of Sydney Plant Species Part 4: Dicotyledon family Fabaceae" (PDF). Cunninghamia. 4 (4): 552–752 [728–29]. ISSN 0727-9620. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-30.

- Fairley, Alan; Moore, Philip (2000). Native Plants of the Sydney District:An Identification Guide (2nd ed.). Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-7318-1031-7.

- "Acacia parramattensis Tindale". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- Elliot, Rodger W.; Jones, David L.; Blake, Trevor (1985). Encyclopaedia of Australian Plants Suitable for Cultivation: Vol. 2. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Lothian Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-85091-143-5.

- Pedley, Les (2003). "A synopsis of Racosperma C.Mart. (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae)". Austrobaileya. 6 (3): 445–96.

- Brown, Gillian K.; Ariati, Siti R.; Murphy, Daniel J.; Miller, Joseph T. H.; Ladiges, Pauline Y. (2006). "Bipinnate acacias (Acacia subg. Phyllodineae sect. Botrycephalae) of eastern Australia are polyphyletic based on DNA sequence data". Australian Systematic Botany. 19 (4): 315–26. doi:10.1071/SB05039.

- Major, Richard (2011). "Southern Highlands Shale Woodlands in the Sydney Basin Bioregion - Determination to make a minor amendment to Part 3 of Schedule 1 of the Threatened Species Conservation Act". State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- AcaciaSearch Acacia parramattensis Tindale. p.154. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Morrison, David A.; Renwick, John A. (2000). "Effects of Variation in Fire Intensity on Regeneration of Co-occurring Species of Small Trees in the Sydney Region". Australian Journal of Botany. 48 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1071/bt98054.

- Edwards, E. D.; Newland, J.; Regan, L. (2001). Lepidoptera. Vol. 31: Hesperioidea, Papilionoidea. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 222, 264–65. ISBN 9780643067004.

- Jones, Bill and Noela (209). "Acacias, Butterflies and Ants". Australian Plants Online. Australian Plants Society (Australia). Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Bellamy, C.L. (2002). Coleoptera. Vol. 29: Buprestoidea. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 158, 347, 350. ISBN 9780643069008.

- Hornsby Shire Council. "Acacia parramattensis - Parramatta green wattle" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- Downey, Paul O. (1998). "An inventory of host species for each aerial mistletoe species (Loranthaceae and Viscaceae) in Australia". Cunninghamia. 5 (3): 685–720.

- Bodkin, Frances; Bodkin-Andrews, Gawaian. "Doo'ragai Diday Boo'Kerrikin: The Sisters Boo'kerrikin" (PDF). D’harawal DREAMING STORIES.

- Hastings, Richard A.; Beattie, Andrew J. (2006). "Stop the bullying in the corridors: Can including shrubs make your revegetation more Noisy Miner free?". Ecological Management & Restoration. 7 (2): 105–12. doi:10.1111/j.1442-8903.2006.00264.x.

External links

Media related to Acacia parramattensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Acacia parramattensis at Wikimedia Commons