Australian frontier wars

The Australian frontier wars were the violent conflicts between Indigenous Australians (including both Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) and primarily British settlers during the colonial period of Australia.[5] The first conflict took place several months after the landing of the First Fleet in January 1788, and the last frontier conflicts occurred in the early 20th century following the federation of the Australian colonies in 1901, with some occurring as late as 1934. An estimated minimum of 100,000 Indigenous Australians and 2,000-2,500 settlers died in the conflicts.[4] Conflicts occurred in a number of locations across Australia.

| Australian frontier wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

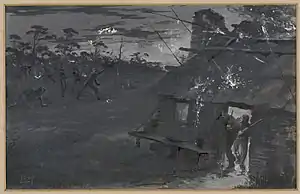

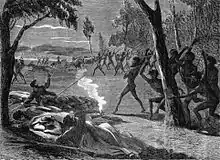

New South Wales Mounted Police engaging Aboriginal warriors during the Waterloo Creek massacre of 1838 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Aboriginal Australians: Eora, Dharug, Gandangara and Tharawal Wiradjuri Wonnarua and Gamilaroi Gunditjmara Palawa peoples Noongar peoples Jagera Many others | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Others |

Pemulwuy Musquito Windradyne Yagan Tunnerminnerwait Truganini Tarenorerer Multuggerah Jandamarra Dundalli Mannalargenna Nemarluk Tarrarer Cocknose Partpoaermin Koort Kirrup Alkapurata | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minimum 2,000 highest 20,000 dead[3] | 100,000-115,000 dead[4] | ||||||

Background and population

In 1770 an expedition from Great Britain under the command of then-Lieutenant James Cook made the first voyage by the British along the Australian east coast. On 29 April, Cook and a small landing party fired on a group of the local Dharawal nation who had sought to prevent them from landing at the foot of their camp at Botany Bay, described by Cook as "a small village". Two Dharawal men made threatening gestures and threw a stone at Cook's party. Cook then ordered "a musket to be fired with small-shot" and the elder of the two was hit in a leg. This caused the two Dharawal men to run to their huts and seize their spears and shields. Subsequently, a single spear was thrown toward the British party, which "happily hurt nobody". This then caused Cook to order "the third musket with small-shots" to be fired, "upon which one of them threw another lance and both immediately ran away".[6] Cook did not make further contact with people of the Dharawal nation.

In his voyage up the east coast of Australia, Cook claimed to have observed no signs of agriculture or other development by its inhabitants. Some historians have argued that under prevailing European law such land was deemed terra nullius or land belonging to nobody[7] or land "empty of inhabitants" (as defined by Emerich de Vattel),[8] though this doctrine was overturned by the High Court of Australia decision in Mabo v Queensland (No 2).[9] Cook wrote that he formally took possession of the east coast of New Holland on 22 August 1770 when on Possession Island off the west coast of Cape York Peninsula.[10]

The British Government decided to establish a prison colony in Australia in 1786.[11] The law system practiced by Indigenous Australians was not necessarily understood or recognised in any official respect by settlers (language barriers made communication extremely difficult), and the English-speaking colony abided by its own legal doctrine.[7] The colony's Governor, Captain Arthur Phillip, was instructed to "live in amity and kindness" with Indigenous Australians and sought to avoid conflict.[12]

The British colonisation of Australia commenced with the First Fleet in mid-January 1788 in the south-east in what is now the federal state of New South Wales. This process then continued into Tasmania and Victoria from 1803 onward. Since then the population density of non-Indigenous people has remained highest in this region of the Australian continent. However, conflict with Aboriginal people was never as intense and bloody in the south-eastern colonies as in Queensland and the continent's northeast. More settlers, as well as Indigenous Australians, were killed on the Queensland frontier than in any other Australian colony. The reason is simple, and is reflected in all evidence and sources dealing with this subject: there were more Aboriginal people in Queensland. The territory of Queensland was the single most populated section of pre-contact Indigenous Australia, reflected not only in all pre-contact population estimates but also in the mapping of pre-contact Australia (see Horton's Map of Aboriginal Australia).[13]

The Indigenous population distribution illustrated below is based on two independent sources, firstly on two population estimates made by anthropologists and a social historian in 1930 and in 1988, and secondly on the basis of the distribution of known tribal land.[14]

| State/territory | Share of population in the 1930 estimates | Share of population in the 1988 estimates | Distribution of tribal land |

|---|---|---|---|

| Queensland | 38.2% | 37.9% | 34.2% |

| Western Australia | 19.7% | 20.2% | 22.1% |

| New South Wales | 15.3% | 18.9% | 10.3% |

| Northern Territory | 15.9% | 12.6% | 17.2% |

| Victoria | 4.8% | 5.7% | 5.7% |

| South Australia | 4.8% | 4.0% | 8.6% |

| Tasmania | 1.4% | 0.6% | 2.0% |

All evidence suggests that the territory of Queensland had a pre-contact Indigenous population density more than double that of New South Wales, at least six times that of Victoria, and at least twenty times that of Tasmania. Equally, there are signs that the population density of Indigenous Australia was comparatively higher in the north-eastern sections of New South Wales, and along the northern coast from the Gulf of Carpentaria and westward including certain sections of the Northern Territory and Western Australia.[16]

| State/territory | Population in numbers | Population in percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Queensland | 300,000 | 37.9% |

| Western Australia | 150,000 | 20.2% |

| New South Wales | 160,000 | 18.9% |

| Northern Territory | 100,000 | 12.6% |

| Victoria | 45,000 | 5.7% |

| South Australia | 32,000 | 4.0% |

| Tasmania | 5,000 | 0.6% |

| Estimated total | 795,000 | 100% |

Impact of disease

The effects of disease, loss of hunting grounds and starvation of the Aboriginal population were significant. There are indications that smallpox epidemics may have impacted heavily on some Aboriginal communities, with depopulation in large sections of what is now Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland up to 50% or more, even before the move inland from Sydney of squatters and their livestock.[18] Other diseases hitherto unknown in the Indigenous population—such as the common cold, flu, measles, venereal diseases and tuberculosis—also had an impact, significantly reducing their numbers and tribal cohesion, and so limiting their ability to adapt to or resist invasion and dispossession.[19]

Traditional Aboriginal warfare

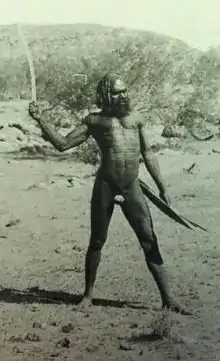

According to the historian John Connor, traditional Aboriginal warfare should be examined on its own terms and not by definitions of war derived from other societies. Aboriginal people did not have distinct ideas of war and peace, and traditional warfare was common, taking place between groups on an ongoing basis, with great rivalries being maintained over extended periods of time.[20] The aims and methods of traditional Aboriginal warfare arose from their small autonomous social groupings. The fighting of a war to conquer enemy territory was not only beyond the resources of any of these Aboriginal groupings, it was contrary to a culture that was based on spiritual connections to a specific territory. Consequently, conquering another group's territory may have been seen to be of little benefit. Ultimately, traditional Aboriginal warfare was aimed at continually asserting the superiority of one's own group over its neighbours, rather than conquering, destroying or displacing neighbouring groups.[21] As the explorer Edward John Eyre observed in 1845, whilst Aboriginal culture was "so varied in detail", it was "similar in general outline and character",[22] and Connor observes that there were sufficient similarities in weapons and warfare of these groups to allow generalisations about traditional Aboriginal warfare to be made.[22]

In 1840, the American-Canadian ethnologist Horatio Hale identified four types of Australian Aboriginal traditional warfare; formal battles, ritual trials, raids for women, and revenge attacks. Formal battles involved fighting between two groups of warriors, which ended after a few warriors had been killed or wounded, due to the need to ensure the ongoing survival of the groups. Such battles were usually fought to settle grievances between groups, and could take some time to prepare. Ritual trials involved the application of customary law to one or more members of a group who had committed a crime such as murder or assault. Weapons were used to inflict injury, and the criminal was expected to stand their ground and accept the punishment. Some Aboriginal men had effective property rights over women and raids for women were essentially about transferring property from one group to another to ensure the survival of a group through women's food-gathering and childbearing roles. The final type of Aboriginal traditional warfare described by Hale was the revenge attack, undertaken by one group against another to punish the group for the actions of one of its members, such as a murder. In some cases these involved sneaking into the opposition camp at night and silently killing one or more members of the group.[23]

Connor describes traditional Aboriginal warfare as both limited and universal. It was limited in terms of:[22]

- the number of members of each group, which restricted the number of warriors in any given engagement;

- the fact that their non-hierarchical social order militated against one leader combining many groups into a single force; and

- duration, due to social groups needing to regularly hunt and forage for food.

Traditional Aboriginal warfare was also universal, as the entire community participated in warfare, boys learnt to fight by playing with toy melee and missile weapons, and every initiated male became a warrior. Women were sometimes participants in warfare as warriors and as encouragers on the sidelines of formal battles, but more often as victims.[24]

While the selection and design of weapons varied from group to group, Aboriginal warriors used a combination of melee and missile weapons in traditional warfare. Spears, clubs and shields were commonly used in hand-to-hand fighting, with different types of shields favoured during exchanges of missiles and in close combat, and spears (often used in conjunction with spear throwers), boomerangs and stones used as missile weapons.[25]

Available weapons had a significant influence over the tactics used during traditional Aboriginal warfare. The limitations of spears and clubs meant that surprise was paramount during raids for women and revenge attacks, and encouraged ambushing and night attacks. These tactics were offset by counter-measures such as regularly changing campsites, being prepared to extinguish camp-fires at short notice, and posting parties of warriors to cover the escape of raiders.[26]

General history

First occupation

Initial peaceful relations between Indigenous Australians and Europeans began to be strained several months after the First Fleet established Sydney on 26 January 1788. The local Indigenous people became suspicious when the British began to clear land and catch fish, and in May 1788 five convicts were killed and an Indigenous man was wounded. The British grew increasingly concerned when groups of up to three hundred Indigenous people were sighted at the outskirts of the colony in June.[27] Despite this, Phillip attempted to avoid conflict, and forbade reprisals after being speared in 1790.[28] He did, however, authorise two punitive expeditions in December 1790 after his huntsman was killed by an Indigenous warrior named Pemulwuy, but neither was successful.[29][30]

Coastal and inland expansion

During the 1790s and early 19th century the British occupied areas along the Australian coastline. These settlements initially occupied small amounts of land, and there was little conflict between the colonisers and Indigenous peoples. Fighting broke out when the settlements expanded, however, disrupting traditional Indigenous food-gathering activities, and subsequently followed the pattern of European invasion in Australia for the next 150 years.[31] Whilst the reactions of the Aboriginal inhabitants to the sudden invasion by the British were varied, they became hostile when their presence led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of their lands. European diseases decimated Indigenous populations, and the occupation or destruction of lands and food resources sometimes led to starvation.[32] By and large neither the Europeans nor the Indigenous peoples approached the conflict in an organized sense, with the conflict more one between groups of colonizers and individual Indigenous groups rather than systematic warfare, even if at times it did involve British soldiers and later formed mounted police units. Not all Indigenous Australians resisted European encroachment on their lands either, whilst many also served in mounted police units and were involved in attacks on other tribes.[32] Colonizers in turn often reacted with violence, resulting in a number of indiscriminate massacres.[33][34] European activities provoking significant conflict included pastoral squatting and gold rushes.

Unequal weaponry

Opinions differ on whether to depict the conflict as one-sided and mainly perpetrated by Europeans on Indigenous Australians or not. Although tens of thousands more Indigenous Australians died than Europeans, some cases of mass killing were not massacres but quasi-military defeats, and the higher death toll was also caused by the technological and logistic advantages enjoyed by Europeans.[33] Indigenous tactics varied, but were mainly based on pre-existing hunting and fighting practices—utilizing spears, clubs and other simple weapons. Unlike the cases with the American Indian Wars and New Zealand Wars, in the main, the indigenous peoples failed to adapt to meet the challenge of the Europeans, and although there were some instances of individuals and groups acquiring and using firearms, this was not widespread.[35] In reality, the Indigenous peoples were never a serious military threat, regardless of how much the settlers may have feared them.[36] On occasions large groups attacked Europeans in open terrain and a conventional battle ensued, during which the Aboriginal residents would attempt to use superior numbers to their advantage. This could sometimes be effective, with reports of them advancing in crescent formation in an attempt to outflank and surround their opponents, waiting out the first volley of shots and then hurling their spears whilst settlers reloaded. Usually, however, such open warfare proved more costly for the Indigenous Australians than the Europeans.[37]

Central to the success of the Europeans was the use of firearms, but the advantages this afforded have often been overstated. Prior to the 19th century, firearms were often cumbersome muzzle-loading, smooth-bore, single shot weapons with flint-lock mechanisms. Such weapons produced a low rate of fire, whilst suffering from a high rate of failure and were only accurate within 50 metres (160 ft). These deficiencies may have given the Aboriginal residents some advantages, allowing them to move in close and engage with spears or clubs. However, by 1850 significant advances in firearms gave the Europeans a distinct advantage, with the six-shot Colt revolver, the Snider single shot breech-loading rifle and later the Martini-Henry rifle as well as rapid-fire rifles such as the Winchester rifle, becoming available. These weapons, when used on open ground and combined with the superior mobility provided by horses to surround and engage groups of Indigenous Australians, often proved successful. The Europeans also had to adapt their tactics to fight their fast-moving, often hidden enemies. Strategies employed included night-time surprise attacks, and positioning forces to drive Aboriginal people off cliffs or force them to retreat into rivers while attacking from both banks.[38]

Dispersed frontiers

Fighting between Indigenous Australians and European settlers was localized, as Indigenous groups did not form confederations capable of sustained resistance. Conflict emerged as a series of violent engagements, and massacres across the continent.[39] According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey, in Australia during the colonial period: "In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralization".[40]

The Caledon Bay crisis of 1932–34 saw one of the last incidents of violent interaction on the "frontier" of indigenous and non-indigenous Australia, which began when the spearing of Japanese poachers who had been molesting Yolngu women was followed by the killing of a policeman. As the crisis unfolded, national opinion swung behind the Aboriginal people involved, and the first appeal on behalf of an Indigenous Australian, Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda, was launched to the High Court of Australia in Tuckiar v The King.[41][42][43] Following the crisis, the anthropologist Donald Thomson was dispatched by the government to live among the Yolngu.[44] Elsewhere around this time, activists like Sir Douglas Nicholls were commencing their campaigns for Aboriginal rights within the established Australian political system and the age of frontier conflict closed.

Frequent friendly relations

Frontier encounters in Australia were not universally negative. Positive accounts of Aboriginal customs and encounters are also recorded in the journals of early European explorers, who often relied on Aboriginal guides and assistance: Charles Sturt employed Aboriginal envoys to explore the Murray-Darling; the lone survivor of the Burke and Wills expedition was nursed by local Aboriginal residents, and the famous Aboriginal explorer Jackey Jackey loyally accompanied his ill-fated friend Edmund Kennedy to Cape York.[45] Respectful studies were conducted by such as Walter Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen in their renowned anthropological study The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899); and by Donald Thomson of Arnhem Land (c.1935–1943). In inland Australia, the skills of Aboriginal stockmen became highly regarded.[46]

New South Wales

Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars

The first frontier war began in 1795 when encroaching British settlers established farms along the Hawkesbury River west of Sydney. Some of these settlements were established by soldiers as a means of providing security to the region.[47] Local Darug people raided farms until Governor Macquarie dispatched a detachment of the 46th Regiment of Foot in 1816. This detachment patrolled the Hawkesbury Valley and ended the conflict by killing 14 Indigenous Australians in an ambush on their campsite.[48] Indigenous Australians led by Pemulwuy also conducted raids around Parramatta during the period between 1795 and 1802. These attacks led Governor Philip Gidley King to issue an order in 1801 which authorised settlers to shoot Indigenous Australians on sight in Parramatta, Georges River and Prospect areas.[30]

Bathurst War

Conflict began again when the British expanded into inland New South Wales. Settlers who crossed the Blue Mountains were harassed by Wiradjuri warriors, who killed or wounded stock-keepers and stock and were subjected to retaliatory killings. In response, Governor Brisbane proclaimed martial law on 14 August 1824 to end "the Slaughter of Black Women and Children, and unoffending White Men". It remained in force until 11 December 1824, when it was proclaimed that "the judicious and humane Measures pursued by the Magistrates assembled at Bathurst have restored Tranquillity without Bloodshed".[49][50] There is a display of the weaponry and history of this conflict at the National Museum of Australia.[51] This includes a commendation by Governor Brisbane of the deployment of the troops under Major Morisset:

I felt it necessary to augment the Detachment at Bathurst to 75 men who were divided into various small parties, each headed by a Magistrate who proceeded in different directions in towards the interior of the Country ... This system of keeping these unfortunate People in a constant state of alarm soon brought them to a sense of their Duty, and ... Saturday their great and most warlike Chieftain has been with me to receive his pardon and that He, with most of His Tribe, attended the annual conference held here on the 28th Novr....[52]

Brisbane also established the New South Wales Mounted Police, who began as mounted infantry from the third Regiment, and were first deployed against bushrangers around Bathurst in 1825. Later they were deployed to the upper Hunter Region in 1826 after fighting broke out there between Wonnarua and Kamilaroi people and settlers.[53]

Wars on the plains

From the 1830s settlers spread rapidly through inland eastern Australia, leading to widespread conflict. War took place across the Liverpool Plains, with 16 British and up to 500 Indigenous Australians being killed between 1832 and 1838. The violence in this region included several massacres of Indigenous people, including the Waterloo Creek massacre and Myall Creek massacres in 1838, and did not end until 1843. Further violence took place in the New England region during the early 1840s.[54]

Tasmania

The British established a settlement in Van Diemen's Land (modern Tasmania) in 1803. Relations with the local Indigenous people were generally peaceful until the mid-1820s when pastoral expansion caused conflict over land. This led to sustained frontier warfare (the "Black War"), and in some districts farmers were forced to fortify their houses.[48] Over 50 British were killed between 1828 and 1830 in what was the "most successful Aboriginal resistance in Australia's history".[57]

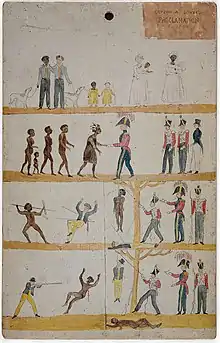

In 1830 Lieutenant-Governor Arthur attempted to end the "Black War" through a massive offensive. In an operation which became known as the "Black Line" ten percent of the colony's male civilian population were mobilised and marched across the settled districts in company with police and soldiers in an attempt to clear Indigenous Australians from the area. While few Indigenous people were captured, the operation discouraged the Indigenous raiding parties, and they gradually agreed to leave their land for a reservation which had been established at Flinders Island.[48]

Western Australia

The first British settlement in Western Australia was established by a detachment of soldiers at Albany in 1826. Relations between the garrison and the local Minang people were generally good. Open conflict between people of the Noongar nation and European settlers broke out in Western Australia in the 1830s as the Swan River Colony expanded from Perth. The Pinjarra massacre, the best known single event, occurred on 28 October 1833 when a party of British colonisers led by Governor Stirling attacked an Indigenous campsite on the banks of the Murray River.[48]

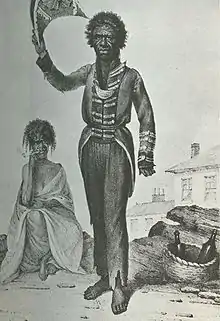

The Noongar nation, forced from traditional hunting grounds and denied access to sacred sites, turned to stealing settlers' crops and killing livestock to survive. In 1831 a Noongar person was murdered for taking potatoes; this resulted in Yagan killing a servant of the household, as was the response permitted under Noongar law. In 1832 Yagan and two others were arrested and sentenced to death, but settler Robert Menli Lyon argued that Yagan was defending his land from invasion and therefore should be treated as a prisoner of war. The argument was successful and the three men were exiled to Carnac Island under the supervision of Lyon and two soldiers. The group later escaped from the island.[58]

Fighting continued into the 1840s along the Avon River near York.[48]

In the Busselton region, relations between white settlers and the Wardandi people were strained to the point of violence, resulting in several Aboriginal deaths. In June 1841, George Layman was speared to death by Wardandi Elder Gaywal.[59] According to one source, Layman had got involved in an argument between Gaywal and another Wardandi person over their allocation of damper, and had pulled Gaywal's beard, which was considered a grave insult. According to another source, Layman had hired two of Gaywal's wives to work on his farm and would not let them go back to their husbands.[59][60] A manhunt for Layman's killer went on for several weeks, involving much bloodshed as Captain John Molloy, the Bussell brothers, and troops murdered unknown numbers of Aboriginal residents in what has become known as the Wonnerup massacre.[61] The posse eventually murdered Gaywal and abducted his three sons, two of whom were imprisoned on Rottnest Island.[59]

The discovery of gold near Coolgardie in 1892 brought thousands of prospectors onto Wangkathaa land, causing sporadic fighting.[62]

Continued European settlement and expansion in Western Australia led to further frontier conflict, Bunuba warriors also attacked European settlements during the 1890s until Bunuba leader Jandamarra was killed in 1897.[62] Sporadic conflict continued in northern Western Australia until the 1920s, with a Royal Commission held in 1926 finding that at least eleven Indigenous Australians had been murdered in the Forrest River massacre by a police expedition in retaliation for the death of a European.[63]

South Australia

South Australia was settled in 1836 with no convicts and a unique plan for settlers to purchase land in advance of their arrival, which was intended to ensure a balance of landowners and farm workers in the colony. The Colonial Office was very conscious of the recent history of the earlier occupations in the eastern states, where there was a significant conflict with the Aboriginal population. On the initial Proclamation Day in 1836 Governor Hindmarsh, made a brief statement that explicitly stated how the native population should be treated. He said in part:

It is also, at this time especially, my duty to apprize the Colonists of my resolution, to take every lawful means of extending the same protection to the native population as to the rest of His Majesty's Subjects, and of my firm determination to punish with exemplary severity, all acts of violence or injustice which may in any manner be practiced or attempted against the natives, who are to be considered as much under the Safeguard of the law as the Colonists themselves, and equally entitled to the privileges of British Subjects.[64]

Governor Gawler declared in 1840 that Aboriginal people "have exercised distinct, defined, and absolute right or proprietary and hereditary possession ... from time immemorial".[65] The Governor ordered land to be set aside for the Aboriginal population, but there was bitter opposition from settlers who insisted on a right to choose the best land. Eventually, the land was available to Aboriginal people only if it promoted their "Christianisation" and they became farmers.[64]

The designation of the Aboriginal population as British citizens gave them rights and responsibilities of which they had no knowledge and ignored existing Aboriginal customary law.[66] However, Aboriginal people could not testify in court, since, not being Christians, they could not swear an oath on a bible. There was also great difficulty in translation. The intentions of those establishing and leading the new colony soon came into conflict with the fears of Aboriginal people and the new settlers. "In South Australia, as across Australia's other colonies, the failure to adequately deal with Aboriginal rights to land was fundamental to the violence that followed."[67]

Soon after the colony was established, large numbers of sheep and cattle were brought overland from the eastern colonies. There were many instances of conflict between Aboriginal people and the drovers, with the former desiring the protection of the Country and the latter quick to shoot to protect themselves and their flocks. One expedition leader (Buchanan) recorded at least six conflicts and the deaths of eight Aboriginal people.[68]

In 1840 the ship Maria was wrecked at Cape Jaffa, on the southeast coast. A search party found that all 26 survivors of the wreck had been massacred. The Governor summoned the Executive Council under martial law and a police party was sent to the district to deliver summary justice against the local Indigenous people. The police party apprehended a number of Aboriginal people; two men were implicated, tried by a tribunal from members of the expedition, found guilty, and hanged. There was a vigorous debate in the colony between those approving the immediate punishment for the massacre and those condemning this form of justice outside the normal law.[67]

The town of Port Lincoln, which was readily accessible by sea from Adelaide, became an early new settlement. A small number of shepherds began to steal land that was home to a large Aboriginal population. Deaths on both sides occurred and settlers demanded better protection.[64] Police and soldiers were sent to the Eyre Peninsula but were often ineffective due to the size of the area and the number of isolated settlements. By the mid-1840s, after conflicts sometimes involving large numbers of Aboriginal people, the greater lethality of the white people's weapons had an effect. Several alleged leaders of attacks by Aboriginal people were tried and executed in Adelaide.[69]

The experience of the Port Lincoln settlement on the Eyre Peninsula was repeated in the South East of the state and in the north as settlers encroached on the Aboriginal population. The government attempted to apply the sentiments of the state's proclamation, but the contradictions between these sentiments and the dispossession that the settlement involved made conflict inevitable.

Victoria

Fighting also took place in early pre-separation Victoria after it was settled in 1834.

In 1833–34, the battle for rights to a beached whale between whalers and people of the Gunditjmara nation resulted in the Convincing Ground massacre near Portland, Victoria.

The 1836 Mount Cottrell massacre was a reprisal for the killing of a prominent Van Diemen's Land squatter Charles Franks who squatted on land west of the Melbourne's fledgling settlement.

A clash at Benalla in 1838 known as the Battle of Broken River of which at least seven white settlers were killed, marked the beginning of the frontier conflict in the colony which lasted for fifteen years.

In 1839 the reprisal raid against Aboriginal resistance in central Victoria resulted in the Campaspe Plains massacre.

The Indigenous groups in Victoria concentrated on economic warfare, killing tens of thousands of sheep. Large numbers of British settlers arrived in Victoria during the 1840s and rapidly outnumbered the Indigenous population.

From 1840, the Eumerella Wars took place in southwest Victoria, and many years of violence occurred during the Warrigal Creek and Gippsland massacres.

In 1842, white settlers from the Port Fairy area wrote a letter to the Charles Latrobe requesting the government improve security from "outrages committed by natives" and listing many incidents of conflict and economic warfare. An excerpt of the letter printed on 10 June:

We, the undersigned, settlers, and inhabitants of the district of Port Fairy, beg respectfully to represent to your Honor the great and increasing want of security to life and property which exists here at present, in consequence of the absence of any protection against the natives. Their number, their ferocity, and their cunning render them peculiarly formidable, and the outrages of which they are daily and nightly guilty, and which they accomplish generally with impunity and success, may, we fear, lead to a still more distressing state of things, unless some measures, prompt and effective, be immediately taken to prevent matters coming to that unhappy crisis.[70]

In the late 1840s, frontier conflict continued in the Wimmera.[71]

Queensland

The frontier wars were particularly bloody and bitter in Queensland, owing to its comparatively large Indigenous population. This point is emphasised in a 2011 study by Ørsted-Jensen, which by use of two different sources calculated that colonial Queensland must have accounted for upwards of one-third and close to forty percent of the Indigenous population of the pre-contact Australian continent.[72]

Queensland represents the single bloodiest colonial frontier in Australia.[73][74] Thus the records of Queensland document the most frequent reports of shootings and massacres of Indigenous people, the three deadliest massacres on white settlers, the most disreputable frontier police force, and the highest number of white victims to frontier violence on record in any Australian colony.[75] In 2009 professor Raymond Evans calculated the Indigenous fatalities caused by the Queensland Native Police Force alone as no less than 24,000.[76] In July 2014, Evans, in cooperation with the Danish historian Robert Ørsted-Jensen, presented the first-ever attempt to use statistical modeling and a database covering no less than 644 collisions gathered from primary sources, and ended up with total fatalities suffered during Queensland's frontier wars being no less than 66,680—with Aboriginal fatalities alone comprising no less than 65,180[77]—whereas the hitherto commonly accepted minimum overall continental deaths had previously been 20,000.[78][79] The 66,680 covers Native Police and settler-inflicted fatalities on Aboriginal people, but also a calculated estimate for Aboriginal inflicted casualties on whites settlers and their associates. The continental death toll of Europeans and associates has previously been roughly estimated as between 2,000 and 2,500, yet there is now evidence that Queensland alone accounted for an estimated 1,500 of these fatal frontier casualties.[3][80]

The European settlement of what is now Queensland commenced as the Moreton Bay penal settlement from September 1824. It was initially located at Redcliffe but moved south to Brisbane River a year later. Free settlement began in 1838, with settlement rapidly expanding in a great rush to take up the surrounding land in the Darling Downs, Logan and Brisbane Valley and South Burnett onwards from 1840, in many cases leading to widespread fighting and heavy loss of life. The conflict later spread north to the Wide Bay and Burnett River and Hervey Bay region, and at one stage the settlement of Maryborough was virtually under siege.[81] Both sides committed atrocities, with settlers poisoning a large number of Indigenous people, for example at Kilcoy on the South Burnett in 1842 and on Whiteside near Brisbane in 1847, and Indigenous warriors killing 19 settlers during the Cullin-La-Ringo massacre on 17 October 1861.[48] At the Battle of One Tree Hill in September 1843, Multuggerah and his group of warriors ambushed one group of settlers, routing them and subsequently others in the skirmishes which followed, starting in retaliation for the Kilcoy poisoning.[82][83]

Queensland's Native Police Force was formed by the Government of New South Wales in 1848, under the well-connected Commandant Frederick Walker.[84]

Major massacres

The largest reasonably well-documented massacres in southeast Queensland were the Kilcoy and Whiteside poisonings, each of which was said to have taken up to 70 Aboriginal lives by use of a gift of flour laced with strychnine. Central Queensland was particularly hard hit during the 1860s and 1870s, several contemporary writers mention the Skull Hole, Bladensburg, or Mistake Creek massacre[lower-alpha 1] on Bladensburg Station near Winton, which in 1901 was said to have taken up to 200 Aboriginal lives.[85]

In 1869 the Port Denison Times reported that "Not long ago 120 aboriginals disappeared on two occasions forever from the native records".[86] Frontier violence peaked on the northern mining frontier during the 1870s, most notably in Cook district and on the Palmer and Hodgkinson River goldfields, with heavy loss of Aboriginal lives and several well-known massacres. Battle Camp and Cape Bedford belong among the best-known massacres of Aboriginal people in the Cook district, but they were certainly not the only ones. The Cape Bedford massacre on 20 February 1879 alone was reported to have taken as many as 28 lives, this was retaliation for the injuring (but not killing) of two white "cedar-getters" from Cooktown.[87] In January 1879 Carl Feilberg, the editor of the short-lived Brisbane Daily News (later editor-in-chief of the Brisbane Courier), conveyed a report from a "gentleman, on whose words reliance can be placed" that he had after just "one of these raids ... counted as many as seventy-five natives dead or dying upon the ground".[88]

Raids conducted by the Kalkadoon held settlers out of Western Queensland for ten years until September 1884 when they attacked a force of settlers and native police at Battle Mountain near modern Cloncurry. The subsequent battle of Battle Mountain ended in disaster for the Kalkadoon, who suffered heavy losses.[89] Fighting continued in North Queensland, however, with Indigenous raiders attacking sheep and cattle while native police mounted punitive expeditions.[62] Two reports from 1884 and 1889 written by one of the prime combatants of the Kalkadoons, Sub-inspector of Native Police (later Queensland Police Commissioner) Frederic Charles Urquhart described how he and his detachment pursued and killed up to 150 Aboriginal people in just three or four so-called "dispersals" (he provided numbers up to about 80 of these killings, the rest was just described without estimating the actual toll).[90]

The conflict in Queensland was the bloodiest in the history of colonial Australia. Some studies give evidence of some 1,500 whites and associates (meaning Aboriginal servants, as well as Chinese, Melanesian, and other non-Europeans) killed on the Queensland frontier during the 19th century, while others suggest that upwards of 65,000 Aboriginal people were killed, with sections of Central and North Queensland witnessing particularly heavy fighting. 65,000 is, of course, an estimate, and notably much higher than the more commonly-held belief of a national minimum of 20,000 colonial Aboriginal casualties.[77]

Some sources have characterized these events as genocide.[91][92][93][94][95][96]

Northern Territory

The British made three early attempts to establish military outposts in northern Australia. The initial settlement at Fort Dundas on Melville Island was established in 1824 but was abandoned in 1829 due to attacks from the local Tiwi people. Some fighting also took place near Fort Wellington on the Cobourg Peninsula between its establishment in 1827 and abandonment in 1829. The third British settlement, Fort Victoria, was also established on the Cobourg Peninsula in 1838 but was abandoned in 1849.[48]

The final battles took place in the Northern Territory. A permanent settlement was established at modern-day Darwin in 1869 and attempts by pastoralists to occupy Indigenous land led to conflict.[62] This fighting continued into the 20th century, and was driven by reprisals against European deaths and the pastoralists' desire to secure the land they had stolen from Indigenous people. At least 31 Indigenous men were killed by police in the Coniston massacre in 1928 and further reprisal expeditions were conducted in 1932 and 1933.[97]

Historiography

Armed resistance to British invasion was generally given little attention by historians until the 1970s, and was not regarded as a "war". In 1968 anthropologist W. E. H. Stanner wrote that historians' failure to include Indigenous Australians in histories of Australia or acknowledge the Frontier Wars constituted a "great Australian silence". Works which discussed the conflicts began to appear during the 1970s and 1980s, and the first history of the Australian frontier told from an Indigenous perspective, Henry Reynolds' The Other Side of the Frontier, was published in 1982.[62]

Between 2000 and 2002 Keith Windschuttle published a series of articles in the magazine Quadrant and the book The Fabrication of Aboriginal History. These works argued that there had not been prolonged frontier warfare in Australia, and that historians had in some instances fabricated evidence of fighting. Windschuttle's claims led to the so-called "history wars" in which historians debated the extent of the conflict between Indigenous Australians and European settlers.[62]

The frontier wars are not commemorated at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The Memorial argues that the Australian frontier fighting is outside its charter as it did not involve Australian military forces. This position is supported by the Returned and Services League of Australia but is opposed by many historians, including Geoffrey Blainey, Gordon Briscoe, John Coates, John Connor, Ken Inglis, Michael McKernan and Peter Stanley. These historians argue that the fighting should be commemorated at the Memorial as it involved large numbers of Indigenous Australians and paramilitary Australian units.[99] In September 2022, after the premiere of the SBS documentary series The Australian Wars, the War Memorial's outgoing chair, former government minister Brendan Nelson announced the Memorial's governing council would work towards a "much broader, a much deeper depiction and presentation of the violence committed against Indigenous people, initially by British, then by pastoralists, then by police, and then by Aboriginal militia".[100] In response to the announcement, filmmaker Rachel Perkins said, "In the making of our series, we worked closely with the War Memorial ... [but] I never saw this coming. I thought, 'Maybe in a generation'... but not right now ... It is a watershed moment in Australian history. It can't be underestimated, the change that this heralds."[101]

See also

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- List of conflicts in Australia

- Musquito a warrior of the Gai-Mariagal nation

- Tarenorerer, also known as Walyer, Waloa or Walloa was a rebel leader of the Indigenous Australians in Tasmania

- Tunnerminnerwait was an Australian Aboriginal resistance fighter and from the Parperloihener nation in Tasmania

- Windradyne warrior and resistance leader of the Wiradjuri nation

- Arauco War and Conquest of the Desert, comparable events in Chile and Argentina

- Historical Records of Australia

- The Great Trek, Xhosa Wars, and Anglo-Zulu war; comparable events in South Africa

- Russian conquest of the Caucasus; comparable events in Russia

Footnotes

- Not to be confused with the 1915 Mistake Creek massacre in Western Australia.

Citations

- Coates (2006), p. 12.

- Connor (2002), p. xii.

- Grey (2008), p. 39.

- Reynolds (2021), pp. 191–192.

- Connor (2002), pp. xi–xii.

- Williams 1997, p. 95.

- Macintyre (1999), p. 34.

- Knop (2002), p. 128.

- "Terra nullius". Australian Museum. 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- Beaglehole, J.C. (1955). The Journals of Captain James Cook. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society. p. 387. ISBN 0851157440.

- Macintyre (1999), p. 30.

- Broome (1988), p. 93.

- "Map of Aboriginal Australia " Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet". ecu.edu.au. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- Ørsted-Jensen 2011, pp. 6–15.

- Statistics compiled by Ørsted-Jensen 2011, pp. 10–11 & 15. Column one is the distribution percentage calculated on the estimates gathered and publicized in 1930 (Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia XXIII, 1930, pp 672, 687–696) by the social anthropologist Alfred Radcliffe-Brown. The percentage in column two was calculated on the basis of N.G. Butlin: Our Original Aggression and "others", by M. D. Prentis for his book A Study in Black and White (2 revised edition, Redfern NSW 1988, page 41). Column three, however, is calculated on the basis of the "Aboriginal Australia" map, published by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra 1994.

- Statistics compiled by Ørsted-Jensen 2011, pp. 10–11 & 15, see more in ref above.

- Statistics compiled by Ørsted-Jensen 2011, pp. 15. The figures and percentage in column two was calculated on the basis of N.G. Butlin: Our Original Aggression and "others", by M. D. Prentis for his book A Study in Black and White (2 revised edition, Redfern NSW 1988, page 41).

- Butlin (1983).

- Dennis et al. (1995), p. 11.

- Connor (2002), pp. 2–3.

- Connor (2002), pp. 3–4.

- Connor (2002), p. 4.

- Connor (2002), pp. 5–8.

- Connor (2002), pp. 4–5.

- Connor (2002), pp. 8–12.

- Connor (2002), pp. 12–13.

- Broome (1988), p. 94.

- Macintyre (1999), p. 33.

- Connor (2002), pp. 31–33.

- Kohen, J. L. (2005). Pemulwuy (c. 1750 – 1802). Retrieved 12 July 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Connor (2002), pp. 33–34.

- Dennis et al. (1995), p. 9.

- Dennis et al. (1995), p. 12.

- Grey (1999), p. 31.

- Dennis et al. (1995), p. 5.

- Grey (1999), p. 30.

- Dennis et al. (1995), pp. 12–13.

- Dennis et al. (1995), pp. 7–8.

- Macintyre (1999), p. 62.

- Blainey (2003), p. 313.

- Egan, Ted (1996). Justice All Their Own: Caledon Bay and Woodah Island Killings 1932-1933. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0522846939.

- Murray, Tom; Collins, Allan (2004). "Dhakiyarr vs the King". Film Australia. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014.

- Tuckiar v The King [1934] HCA 49, (1934) 52 CLR 335, High Court.

- Dewar, Mickey (2005). Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda (1900–1934). Retrieved 29 July 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Flannery, Tim (1998). The Explorers. Text Publishing.

- "The Wave Hill 'walk-off' – Fact sheet 224". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- Macintyre (1999), p. 38.

- Connor (2008), p. 220.

- "Text of Proclamation of Martial Law". National Library of Australia.Note: "Measure" made plural to align with "have".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Text of Proclamation ending Martial Law". National Library of Australia.

- "Bells Falls Gorge – virtual tour". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- Sir Thomas Brisbane to Earl Bathurst, Despatch No.18 per ship Mangles,Government House, N.S. Wales, 31 December 1824.

- Connor (2008), p. 62.

- Broome (1988), p. 101.

- "Governor Arthur's proclamation". National Treasures from Australia's Great Libraries. National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- "Governor Daveys Proclamation to the Aborigines". Manuscripts, Oral History & Pictures. State Library of New South Wales. 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- Broome (1988), p. 96.

- Hasluck, Alexandra (1967). "Yagan ( – 1833)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- Stirling, Ros. "Wonnerup: a chronicle of the south-west". Australian Heritage magazine. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- "The Western Australian Journal". The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal. National Library of Australia. 13 March 1841. p. 3. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- There are no official records of the massacre and sources suggest anywhere from five to 300 were killed. A newspaper report of the time states that only five were killed: "The Western Australian Journal". The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal. National Library of Australia. 13 March 1841. p. 3. Retrieved 23 April 2011. However, according to Warren Bert Kimberly's History of West Australia (1897), relying on local memories: "The black men were killed by dozens, and their corpses lined the route of march of the avengers. ... On the sand patch near Mininup, skeletons and skulls of natives reported to have been killed in 1841 are still to be found. ... Surviving natives held the place in such terror that they would not go near to give the burial of the corpses. Even now natives refuse to disturb the bones.": . Melbourne: F. W. Niven. 1897. p. 116. Kimberly gives no more precise number. More recent sources quote a number of 250 to 300, though none of these appear to be supported anywhere other than the oral history of unknown origin.

- Connor (2008), p. 221.

- Broome (1988), pp. 108–109.

- Foster & Nettlebeck (2012), p. 21.

- Foster & Nettlebeck (2012), p. 24.

- Foster & Nettlebeck (2012), p. 22.

- Foster & Nettlebeck (2012), p. 25.

- Foster & Nettlebeck (2012), p. 34.

- Foster & Nettlebeck (2012), p. 42.

- "The settlers and the blacks of Port Fairy". Southern Australian. 10 June 1842. Retrieved 4 December 2018 – via Trove, National Library of Australia.

- Broome (1988), pp. 102–103.

- Ørsted-Jensen (2011), pp. 10–11.

- Loos, Noel (1970). Frontier conflict in the Bowen district 1861–1874 (other). James Cook University of North Queensland. doi:10.25903/mmrc-5e46. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Loos, Noel (1976). Aboriginal-European relations in North Queensland, 1861–1897 (PhD). James Cook University. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Ørsted-Jensen (2011).

- Evans, Raymond (October 2011) The country has another past: Queensland and the History Wars, in Passionate Histories: Myth, memory, and Indigenous Australia Aboriginal History Monograph 21. Edited by Frances Peters-Little, Ann Curthoys and John Docker (Peters-Little, Curthoys & Docker 2011)

- Evans, Raymond & Ørsted–Jensen, Robert: 'I Cannot Say the Numbers that Were Killed': Assessing Violent Mortality on the Queensland Frontier" (paper at AHA 9 July 2014 at University of Queensland) publisher Social Science Research Network

- Reynolds (1982), pp. 121–127.

- Reynolds (1987), p. 53.

- Reynolds (1982), pp. 121–127; Reynolds (1987), p. 53; Ørsted-Jensen (2011), pp. 16–20 and Appendix A: Listing the Death Toll of the Invader

- Broome (1988), p. 102.

- Kerkhove, Ray (19 August 2017). "Battle of One Tree Hill and Its Aftermath". Retrieved 5 August 2020. Note: Dr Ray Kerkhove, owner of this site, is a reputable historian. See here and here.

- Marr, David (14 September 2019). "Battle of One Tree Hill: remembering an Indigenous victory and a warrior who routed the whites". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Skinner (1975), p. 26.

- Queenslander 20 April 1901, page 757d-758c and Carl Lumholtz Among Cannibals (London 1889) page 58–59; See also Bottoms 2013, pp. 172–174.

- Port Denison Times, 1 May 1869, page 2g and the Empire (Sydney) 25 May 1869, page 2.

- Queenslander, 8 March 1879, page 313d

- Daily News (formerly Queensland Patriot), 1 January 1879, p2f.

- Coulthard-Clark (2001), pp. 51–52.

- Queensland State Archives A/49714 no 6449 of 1884 (report); QPG re 13 July 1884, Vol 21:213; 21 July 1884 – COL/A395/84/5070; Q 16 August 1884, p253; 20 August 1884 Inquest JUS/N108/84/415; POL/?/84/6449; 15 Queensland Figaro November 1884 and Queensland State Archives A/49714, letter 9436 of 1889.

- Gibbons, Ray. "The Partial Case for Queensland Genocide".

- Baldry, Hannah; McKeon, Alisa; McDougal, Scott. "Queensland's Frontier Killing Times – Facing Up to Genocide". QUT Law Review. 15 (1): 92–113. ISSN 2201-7275.

- Palmer, Alison (1998). "Colonial and modern genocide: explanations and categories". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 21: 89–115. doi:10.1080/014198798330115.

- Tatz, Colin (2006). Maaka, Roger; Andersen, Chris (eds.). "Confronting Australian Genocide". The Indigenous Experience: Global Perspectives. Canadian Scholars Press. 25: 16–36. ISBN 978-1551303000. PMID 19514155.

- Docker, John (13 December 2014). "A plethora of intentions: genocide, settler colonialism and historical consciousness in Australia and Britain". The International Journal of Human Rights. 19 (1): 74–89. doi:10.1080/13642987.2014.987952. S2CID 145745263. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Rogers, Thomas James; Bain, Stephen (3 February 2016). "Genocide and frontier violence in Australia". Journal of Genocide Research. 18 (1): 83–100. doi:10.1080/14623528.2016.1120466. S2CID 147512803. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Broome (1988), p. 109.

- "The Aboriginal Memorial". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- Peacock, Matt (26 February 2009). "War memorial battle over frontier conflict recognition". The 7:30 Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Karvelas, Patricia (2 October 2022). "The Australian War Memorial's promise of a 'deeper depiction' of the frontier wars signals an important new chapter". ABC. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Butler, Dan (30 September 2022). "Rachel Perkins welcomes War Memorial's expansion of frontier conflicts exhibits". NITV. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

References

- Reynolds, Henry (2021). TRUTH-TELLING. Sydney NSW 2052 AUSTRALIA: NewSouth Publishing. ISBN 9781742236940.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Blainey, Geoffrey (2003). A Short History of the World. Lanham: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1461709865.

- Bottoms, Timothy (2013). Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland's frontier killing times. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74331-382-4.

- Broome, Richard (1988). "The Struggle for Australia : Aboriginal-European Warfare, 1770–1930". In McKernan, Michael; Browne, Margaret; Australian War Memorial (eds.). Australia Two Centuries of War & Peace. Canberra, A.C.T.: Australian War Memorial in association with Allen and Unwin, Australia. pp. 92–120. ISBN 0-642-99502-8.

- Butlin, Noel G. (1983). Our Original Aggression: Aboriginal Populations of Southeastern Australia, 1788–1850. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0868612235.

- Coates, John (2006). An Atlas of Australia's Wars. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555914-2.

- Connor, John (2002). The Australian frontier wars, 1788–1838. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 0-86840-756-9.

- Connor, John (2008). "Frontier Wars". In Dennis, Peter; et al. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia & New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris D. (2001). The Encyclopedia of Australia's Battles (Second ed.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1865086347.

- Peters-Little, Frances; Curthoys, Ann; Docker, John, eds. (3 October 2011). Passionate Histories: Myth, memory and Indigenous Australia. Aboriginal History Monograph. Vol. 21. ANU-Press. doi:10.22459/PH.09.2010. ISBN 978-1-921666-64-3. (Estimates of 19th century Aboriginal Frontier death toll, see "Part One, Massacres" chapter 1, The Country Has Another Past: Queensland and the History Wars by Raymond Evans).

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9.

- Evans, Raymond; Ørsted–Jensen, Robert (9 July 2014). I Cannot Say the Numbers that Were Killed': Assessing Violent Mortality on the Queensland Frontier. AHA. University of Queensland: Social Science Research Network (SSRN). (abstract)

- Foster, Robert; Nettlebeck, Amanda (2012). Out of the Silence: the history and memory of South Australia's frontier wars. Adelaide: Wakefield Press. ISBN 9781743055823.

- Grey, Jeffrey (1999). A Military History of Australia (Second ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64483-6.

- Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (Third ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.

- Knop, Karen (May 2002). Diversity and Self-Determination in International Law. Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78178-7. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- Macintyre, Stuart (1999). A Concise History of Australia. Cambridge Concise Histories (First ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62577-7.

- Ørsted-Jensen, Robert (2011). Frontier History Revisited – Queensland and the 'History War'. Cooparoo, Brisbane, Qld: Lux Mundi Publishing. ISBN 9781466386822.

- Reynolds, Henry (1982). The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia. Ringwood: Penguin Books Australia. ISBN 0140224750.

- Williams, Glyndwr, ed. (1997). Captain Cooks Voyages 1768–1779. London: Folio Society. OCLC 38549967.

- Reynolds, Henry (1987). Frontier: Aborigines, Settlers and Land. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-994005-8.

- Skinner, Leslie E. (1975). Police of the Pastoral Frontier: Native Police, 1849–1859. St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0702209775.

Further reading

- "Australian Frontier Conflicts 1788-1940s". Australian Frontier Wars 1788-1940.

- Booth, Andrea (18 April 2016). "What are the Frontier Wars?". NITV (SBS). Explainer.

- Clark, Ian D.; Cahir, Fred; Wilkie, Benjamin; Tout, Dan; Clark, Jidah (27 May 2022). "Aboriginal Use of Fire as a Weapon in Colonial Victoria: A Preliminary Analysis". Australian Historical Studies. 54: 109–124. doi:10.1080/1031461X.2022.2071954. S2CID 249139781.

- Clayton-Dixon, Callum (2019). Surviving New England: a history of Aboriginal resistance & resilience through the first forty years of the colonial apocalypse.

- Connor, John (October 2017). "Climate, Environment and Australian Frontier Wars: New South Wales 1788-1841". The Journal of Military History. 81 (4): 985–1006.

- Foster, Robert; Hosking, Rick; Nettleback, Amanda (2001). Fatal Collisions: The South Australian Frontier and the Violence of Memory. Kent Town: Wakefield Press. ISBN 1-86254-533-2.

- Gapps, Stephen (2018). The Sydney Wars: Conflict in the early colony, 1788-1817. Sydney: NewSouth. ISBN 9781742232140.

- Grassby, Al; Hill, Marji (1988). Six Australian Battlefields. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-672-4.

- Loos, Noel A. (1982). Invasion And Resistance: Aboriginal-European Relations On The North Queensland Frontier 1861–1897. Canberra, Australia; Miami, Fl, USA: Australian National University Press. ISBN 0-7081-1521-7.

- Reynolds, Henry (2013). Forgotten War. Sydney. ISBN 9781742233925.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Aaron (26 May 2018). "The 'forgotten people': When death came to the Torres Strait". CNN.

- Stanley, Peter (1986). The Remote Garrison: The British Army in Australia 1788–1870. Kenthurst: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-091-2.