AP endonuclease

Apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease is an enzyme that is involved in the DNA base excision repair pathway (BER). Its main role in the repair of damaged or mismatched nucleotides in DNA is to create a nick in the phosphodiester backbone of the AP site created when DNA glycosylase removes the damaged base.

There are four types of AP endonucleases that have been classified according to their mechanism and site of incision. Class I AP endonucleases (EC 4.2.99.18) cleave 3′ to AP sites by a β-lyase mechanism, leaving an unsaturated aldehyde, termed a 3′-(4-hydroxy-5-phospho-2-pentenal) residue, and a 5′-phosphate. Class II AP endonucleases incise DNA 5′ to AP sites by a hydrolytic mechanism, leaving a 3′-hydroxyl and a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate residue.[2] Class III and class IV AP endonucleases also cleave DNA at the phosphate groups 3′ and 5′ to the baseless site, but they generate a 3′-phosphate and a 5′-OH.[3]

Humans have two AP endonucleases, APE1 and APE2. APE1 exhibits robust AP-endonuclease activity, which accounts for >95% of the total cellular activity, and APE1 is considered to be the major AP endonuclease in human cells.[4] Human AP endonuclease (APE1), like most AP endonucleases, is of class II and requires an Mg2+ in its active site in order to carry out its role in base excision repair. The yeast homolog of this enzyme is APN1.[5]

Human AP Endonuclease 2 (APE2), like most AP endonucleases, is also of class II. The exonuclease activity of APE2 is strongly dependent upon metal ions. However, APE2 was more than 5-fold more active in the presence of manganese than of magnesium ions.[4] The conserved domains involved in catalytic activity are located at the N-terminal part of both APE1 and APE2. In addition, the APE2 protein has a C-terminal extension, which is not present in APE1, but can also be found in homologs of human APE2 such as APN2 proteins of S. cerevisiae and S. pombe.[4]

Structure of APE1

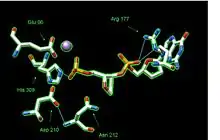

APE1 contains several amino acid residues that enable it to react selectively with AP sites. Three APE1 residues (Arg73, Ala74, and Lys78) contact three consecutive DNA phosphates on the strand opposite the one containing the AP site while Tyr128 and Gly127 span and widen the minor groove, anchoring the DNA for the extreme kinking caused by the interaction between positive residues found in four loops and one α-helix and the negative phosphate groups found in the phosphodiester backbone of DNA.

This extreme kinking forces the baseless portion of DNA into APE1's active site. This active site is bordered by Phe266, Trp280, and Leu282, which pack tightly with the hydrophobic side of the AP site, discriminating against sites that do have bases. The AP site is then further stabilized through hydrogen bonding of the phosphate group 5´ to the AP site with Asn174, Asn212, His309, and the Mg2+ ion while its orphan base partner is stabilized through hydrogen bonding with Met270. The phosphate group 3' to the AP site is stabilized through hydrogen bonding to Arg177. Meanwhile, an Asp210 in the active site, which is made more reactive due to the increase in its pKa (or the negative log of acid dissociation constant) caused through its stabilization through its hydrogen bonding between Asn68 and Asn212, activates the nucleophile that attacks and cleaves the phosphodiester backbone and probably results in the observed maximal APE1 activity at a pH of 7.5.[1]

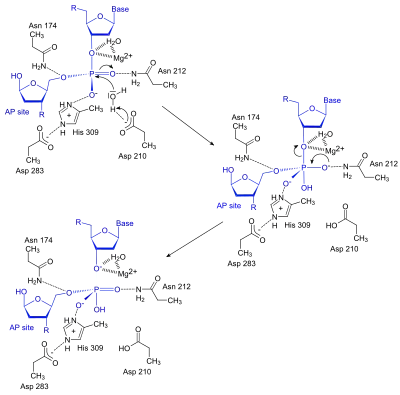

Mechanism

The APE1 enzyme creates a nick in the phosphodiester backbone at an abasic (baseless) site through a simple acyl substitution mechanism. First, the Asp210 residue in the active site deprotonates a water molecule, which can then perform a nucleophilic attack on the phosphate group located 5´ to the AP site. Next, electrons from one of the oxygen atom in the phosphate group moves down, kicking off one of the other oxygen to create a free 5´ phosphate group on the AP site and a free 3´-OH on the normal nucleotide, both of which are stabilized by the Mg2+ ion.[1]

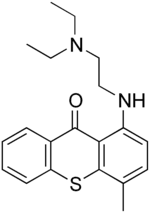

Inhibition of APE1

Known inhibitors of APE1 include 7-nitroindole-2-carboxylic acid (NCA) and lucanthone.[6] Both of these structures possess rings attached to short chains, which appear similar to the deoxyribose sugar ring without a base attached and phosphodiester bond in DNA. Further, both contain many H-bond acceptors which may interact with the H-bond donors in the active site of APE1, causing these inhibitors to stick in the active site and preventing the enzyme from catalyzing other reactions.

APE1 as chemopreventive target

Because APE1 performs an essential function in DNA base-excision repair pathway, it has become a target for researchers looking for means to prevent cancer cells from surviving chemotherapy. Not only is APE1 needed in and of itself to create the nick in the DNA backbone so that the enzymes involved later in the BER pathway can recognize the AP-site, it also has a redox function that helps activate other enzymes involved in DNA repair. As such, knocking down APE1 could lead to tumor cell sensitivity, thus preventing cancer cells from persisting after chemotherapy.[7]

APE2 enzyme activity

APE2 has much weaker AP endonuclease activity than APE1, but its 3'-5' exonuclease activity is strong compared with APE1[8] and it has a fairly strong 3'-phosphodiesterase activity.[4]

The APE2 3' –5' exonuclease activity has the ability to hydrolyze blunt-ended duplex DNA, partial DNA duplexes with a recessed 3' -terminus or a single nucleotide gap containing heteroduplex DNA. The APE2 3'-phosphodiesterase activity can remove modified 3'-termini, such as 3'-phosphoglycolate as well as mismatched nucleotides from the 3' primer end of DNA.[4]

APE2 is required for ATR-Chk1 DNA damage response following oxidative stress.

References

Molecular graphics images were produced using the UCSF Chimera package from the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIH P41 RR-01081).[9]

- Clifford D. Mol; Tahide Izumi; Sankar Mitra; John A. Tainer (2000). "DNA-bound structures and mutants reveal abasic DNA binding by APE1 DNA repair and coordination". Nature. 403 (6768): 451–456. doi:10.1038/35000249. PMID 10667800. S2CID 4373743.

- Levin, Joshua D; Demple, Bruce (1990). "Analysis of class II (hydrolytic) and class I (beta-lyase) apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases with a synthetic DNA substrate". Nucleic Acids Research. 18 (17): 5069–75. doi:10.1093/nar/18.17.5069. PMC 332125. PMID 1698278.

- Gary M. Myles; Aziz Sancar (1989). "DNA Repair". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2 (4): 197–226. doi:10.1021/tx00010a001. PMID 2519777.

- Burkovics P, Szukacsov V, Unk I, Haracska L (2006). "Human Ape2 protein has a 3'-5' exonuclease activity that acts preferentially on mismatched base pairs". Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (9): 2508–15. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl259. PMC 1459411. PMID 16687656.

- George W. Teebor; Dina R. Marensein; David M. Wilson III (2004). "Human AP endonuclease (APE1) demonstrates endonucleolytic activity against AP sites in single-stranded DNA". DNA Repair. 3 (5): 527–533. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.01.010. PMID 15084314.

- Mark R. Kelley; Melissa L. Fishel (2007). "The DNA base excision repair protein Ape1/Ref-1 as a Therapeutic and chemopreventive target". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 28 (3–4): 375–395. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2007.04.005. PMID 17560642.

- Mark R. Kelley; Meihua Luo; Sarah Delaphlane; Aihua Jiang; April Reed; Ying He; Melissa Fishel; Rodney L. Nyland II; Richard F. Broch; Xizoxi Qiao; Millie M. Georgiadis (2008). "Role of the Multifunctional DNA Repair and Redox Signaling Protein Ape1/Ref-1 in Cancer and Endothelial Cells: Small-Molecule Inhibition of the Redox Function of Ape1". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 10 (11): 1–12. doi:10.1089/ars.2008.2120. PMC 2587278. PMID 18627350.

- Stavnezer J, Linehan EK, Thompson MR, Habboub G, Ucher AJ, Kadungure T, Tsuchimoto D, Nakabeppu Y, Schrader CE (2014). "Differential expression of APE1 and APE2 in germinal centers promotes error-prone repair and A:T mutations during somatic hypermutation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 (25): 9217–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405590111. PMC 4078814. PMID 24927551.

- E.F. Pettersen; T.D. Goddard; C.C. Huang; G.S. Couch; D.M. Greenblat; E.C. Meng; T.E. Ferrin (2004). "UCSF Chimera - A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis" (PDF). J. Comput. Chem. 25 (13): 1605–1612. doi:10.1002/jcc.20084. PMID 15264254. S2CID 8747218.

External links

- Basic Definition of AP endonuclease Archived 2010-06-20 at the Wayback Machine

- AP endonucleases family 1 in PROSITE

- AP endonucleases family 2 in PROSITE

- Application in Long Patch Base Excision Repair Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Purification and characterization of an apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease from HeLa cells Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine