AIDA (marketing)

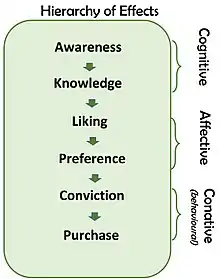

The AIDA model is a model within the class known as hierarchy of effects models or hierarchical models, all of which imply that consumers move through a series of steps or stages when they make purchase decisions. These models are linear, sequential models built on an assumption that consumers move through a series of cognitive (thinking) and affective (feeling) stages culminating in a behavioural (doing e.g. purchase or trial) stage.[1]

| Marketing |

|---|

Steps proposed by the AIDA model

The steps proposed by the AIDA model are as follows:[2][3]

- Attention – The consumer becomes aware of a category, product or brand (usually through advertising)

- ↓

- Interest – The consumer becomes interested by learning about brand benefits & how the brand fits with lifestyle

- ↓

- Desire – The consumer develops a favorable disposition towards the brand

- ↓

- Action – The consumer forms a purchase intention, shops around, engages in trial or makes a purchase

Some of the contemporary variants of the model replace attention with awareness. The common thread among all hierarchical models is that advertising operates as a stimulus (S) and the purchase decision is a response (R). In other words, the AIDA model is an applied stimulus-response model. A number of hierarchical models can be found in the literature including Lavidge's hierarchy of effects, DAGMAR and variants of AIDA. Hierarchical models have dominated advertising theory,[4] and, of these models, the AIDA model is one of the most widely applied.[5]

As consumers move through the hierarchy of effects they pass through both a cognitive processing stage and an affective processing stage before any action occurs. Thus the hierarchy of effects models all include Cognition (C)- Affect (A)- Behaviour (B) as the core steps in the underlying behavioral sequence.[6] Some texts refer to this sequence as Learning → Feeling → Doing or C-A-B (cognitive -affective-behavioral) models.

- Cognition (Awareness/learning) → Affect (Feeling/ interest/ desire) → Behavior (Action e.g. purchase/ trial/ consumption/ usage/ sharing information)[7]

The basic AIDA model is one of the longest serving hierarchical models, having been in use for more than a century. Using a hierarchical system, such as AIDA, provides the marketer with a detailed understanding of how target audiences change over time, and provides insights as to which types of advertising messages are likely to be more effective at different junctures. Moving from step to step, the total number of prospects diminishes. This phenomenon is sometimes described as a "purchase funnel". A relatively large number of potential purchasers become aware of a product or brand, then a smaller subset becomes interested, with only a relatively small proportion moving through to the actual purchase. This effect is also known as a "customer funnel", "marketing funnel", or "sales funnel".[8]

The model is also used extensively in selling and advertising. According to the original model, "the steps to be taken by the seller at each stage are as follows:

- Stage I. Secure attention.

- Stage II. Hold attention Through Interest.

- Stage III. Arouse Desire.

- Stage IV. Create Confidence and Belief.

- Stage V. Secure Decision and Action.

- Stage VI. Create Satisfaction."[9]

Criticisms

A major deficiency of the AIDA model and other hierarchical models is the absence of post-purchase effects such as satisfaction, consumption, repeat patronage behaviour and other post-purchase behavioural intentions such as referrals or participating in the preparation of online product reviews.[10] Other criticisms include the model's reliance on a linear nature, hierarchical sequence. In empirical studies, the model has been found to be a poor predictor of actual consumer behaviour.[11] In addition, an extensive review of the literature surrounding advertising effects, carried out by Vakratsas and Ambler found little empirical support for the hierarchical models.[12]

Another important criticism of the hierarchical models include their reliance on the concept of a linear, hierarchical response process.[13] Indeed, some research suggests that consumers process promotional information via dual pathways, namely both cognitive (thinking) and affective (feeling) simultaneously.[14] This insight has led to the development of a class of alternative models, known as integrative models.[15]

Variants

In order to redress some of the model's deficiencies, a number of contemporary hierarchical models have modified or expanded the basic AIDA model. Some of these include post purchase stages, while other variants feature adaptations designed to accommodate the role of new, digital and interactive media, including social media and brand communities. However, all follow the basic sequence which includes Cognition- Affect- Behaviour.[16]

Selected variants of AIDA:

- Basic AIDA Model: Awareness → Interest → Desire → Action[17]

- Lavidge et al's Hierarchy of Effects: Awareness → Knowledge → Liking → Preference → Conviction → Purchase[18]

- McGuire's model: Presentation → Attention → Comprehension → Yielding → Retention → Behavior.[19]

- Modified AIDA Model: Awareness → Interest → Conviction → Desire → Action (purchase or consumption)[20]

- AIDAS Model: Attention → Interest → Desire → Action → Satisfaction[21]

- AISDALSLove model: Awareness → Interest → Search → Desire → Action → Like/dislike → Share → Love/Hate[22]

Origins

The term, AIDA and the overall approach are commonly attributed to American advertising and sales pioneer, E. St. Elmo Lewis.[23] In one of his publications on advertising, Lewis postulated at least three principles to which an advertisement should conform:

The mission of an advertisement is to attract a reader, so that he will look at the advertisement and start to read it; then to interest him, so that he will continue to read it; then to convince him, so that when he has read it he will believe it. If an advertisement contains these three qualities of success, it is a successful advertisement.[24]

According to F. G. Coolsen, "Lewis developed his discussion of copy principles on the formula that good copy should attract attention, awaken interest, and create conviction."[25] In fact, the formula with three steps appeared anonymously in the February 9, 1898, issue of Printers' Ink: "The mission of an advertisement is to sell goods. To do this, it must attract attention, of course; but attracting attention is only an auxiliary detail. The announcement should contain matter which will interest and convince after the attention has been attracted" (p. 50).

On January 6, 1910 Lewis gave a talk in Rochester on the topic "Is there a science back of advertising?" in which he said:

I can remember with what a feeling of resigned and kindly tolerance some of the old advertising men hear a writer say, 'All advertising must attract attention, maintain interest, arouse desire, get action.' Even that primitive attempt to place advertising art under tribute to formula aroused the ire of the anointed ones of ten years ago, and we had to undergo a good deal of more or less good-natured chaffing. But we don't hear so much about that sort of thing now; some of the "upstart youngsters" of ten years ago are now getting big salaries making that simple formula work.[26]

The importance of attracting the attention of the reader as the first step in copy writing was recognized early in the advertising literature as is shown by the Handbook for Advertisers and Guide to Advertising:

The first words are always printed in capitals, to catch the eye, and it is important that they should be such as will be likely to arrest the attention of those to whom they are addressed, and induced them to read further.[27]

A precursor to Lewis was Joseph Addison Richards (1859–1928), an advertising agent from New York City who succeeded his father in the direction of one of the oldest advertising agencies in the United States. In 1893, Richards wrote an advertisement for his business containing virtually all steps from the AIDA model, but without hierarchically ordering the individual elements:

How to attract attention to what is said in your advertisement; how to hold it until the news is told; how to inspire confidence in the truth of what you are saying; how to whet the appetite for further information; how to make that information reinforce the first impression and lead to a purchase; how to do all these, – Ah, that's telling, business news telling, and that's my business.[28]

Between December 1899 and February 1900, the Bissell Carpet Sweeper Company organized a contest for the best written advertisement. Fred Macey, chairman of the Fred Macey Co. in Grand Rapids (Michigan), who was considered an advertising expert at that time, was assigned the task to examine the submissions to the company. In arriving at a decision, he considered inter alia each advertisement in the following respect:

1st The advertisement must receive "Attention," 2d. Having attention it must create "Interest," 3d. Having the reader's interest it must create "Desire to Buy," 4th. Having created the desire to buy it should help "Decision".[29]

The first published instance of the general concept, however, was in an article by Frank Hutchinson Dukesmith (1866–1935) in 1904. Dukesmith's four steps were attention, interest, desire, and conviction.[30] The first instance of the AIDA acronym was in an article by C. P. Russell in 1921 where he wrote:

An easy way to remember this formula is to call in the “law of association,” which is the old reliable among memory aids. It is to be noted that, reading downward, the first letters of these words spell the opera “Aida.” When you start a letter, then, say “Aida” to yourself and you won’t go far wrong, at least as far as the form of your letter is concerned.[31]

The model's usefulness was not confined solely to advertising. The basic principles of the AIDA model were widely adopted by sales representatives who used the steps to prepare effective sales presentations following the publication, in 1911, of Arthur Sheldon's book, Successful Selling.[32] To the original model, Sheldon added satisfaction to stress the importance of repeat patronage.

AIDA is a linchpin of the Promotional part of the 4Ps of the Marketing mix, the mix itself being a key component of the model connecting customer needs through the organisation to the marketing decisions.[33]

Theoretical developments in hierarchy of effects models

The marketing and advertising literature has spawned a number of hierarchical models.[34] In a survey of more than 250 papers, Vakratsas and Ambler (1999) found little empirical support for any of the hierarchies of effects.[35] In spite of that criticism, some authors have argued that hierarchical models continue to dominate theory, especially in the area of marketing communications and advertising.[36]

All hierarchy of effects models exhibit several common characteristics. Firstly, they are all linear, sequential models built on an assumption that consumers move through a series of steps or stages involving cognitive, affective and behavioral responses that culminate in a purchase.[37] Secondly, all hierarchy of effects models can be reduced to three broad stages - Cognitive→ Affective (emotions)→Behavioral (CAB).[38]

Three broad stages implicit in all hierarchy of effects models:[39]

- Cognition (Awareness or learning)

- ↓

- Affect (Feeling, interest or desire)

- ↓

- Behavior (Action)

Recent modifications of the AIDA model have expanded the number of steps.[40] Some of these modifications have been designed to accommodate theoretical developments, by including customer satisfaction (e.g. the AIDAS model)[41] while other alternative models seek to accommodate changes in the external environment such as the rise of social media (e.g. the AISDALSLove model).[42]

In the AISDALSLove model,[43] new phases are 'Search' (after Interest), the phase when consumers actively searching information about brand/ product, 'Like/dislike' (after Action) as one of elements in the post-purchase phase, then continued with 'Share' (consumers will share their experiences about brand to other consumers) and the last is 'Love/hate' (a deep feeling towards branded product, that can become the long-term effect of advertising) which new elements such as Search, Like/dislike (evaluation), Share and Love/hate as long-term effects have also been added. Finally, S – 'Satisfaction' – is added to suggest the likelihood that a customer might become a repeat customer, provide positive referrals or engage in other brand advocacy behaviors following purchase.

Other theorists, including Christian Betancur (2014)[44] and Rossiter and Percy (1985)[45] have proposed that need recognition should be included as the initial stage of any hierarchical model. Betancur, for example, has proposed a more complete process: NAITDASE model (in Spanish: NAICDASE). Betancur's model begins with the identification of a Need (the consumer's perception of an opportunity or a problem). Following the Attention and Interest stages, consumers form feelings of Trust (i.e., Confidence). Without trust, customers are unlikely to move forward towards the Desire and Action stages of the process. Purchase is not the end stage in this model, as this is not the goal of the client; therefore, the final two stages are the Satisfaction of previously identified and agreed needs and the Evaluation by the customer about the whole process. If positive, it will repurchase and recommend to others (Customer's loyalty).

In Betancur's model, trust is a key element in the purchase process, and must be achieved through important elements including:

- Business and personal image (including superior brand support).

- Empathy with this customer.

- Professionalism (knowledge of the product and master of the whole process from the point of view of the customer).

- Ethics without exceptions.

- Competitive Superiority (to solve the needs and requirements of this customer).

- Commitment during the process and toward the customer satisfaction.

Trust (or Confidence) is the glue that bonds society and makes solid and reliable relations of each one other.

Cultural references

In the film Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet, the character Blake (played by Alec Baldwin) makes a speech where the AIDA model is visible on a chalkboard in the scene. A minor difference between the fictional account of the model and the model as it is commonly used is that the "A" in Blake's motivational talk is defined as attention rather than awareness and the "D" as decision rather than desire.

See also

- Advertising – socio-historical account of advertising

- Advertising campaign

- Advertising media selection

- Ad tracking

- Advertising research

- Advertising management – advertising as a function of marketing management

- AttentionTracking

- Attitude-toward-the-ad models

- Brand awareness

- Consumer behaviour

- DAGMAR marketing

- Integrated marketing communications

- Marketing

- Marketing communications

- Media planning

- Promotion (marketing)

- Promotional mix

- Purchase funnel

- Sales management

- Sales promotion

Advertising models

Notes

- Demetrios Vakratsas and Tim Ambler, "How Advertising Works: What Do We Really Know?" Journal of MarketingVol. 63, No. 1, 1999, pp. 26-43 DOI: 10.2307/1251999 URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1251999

- Priyanka, R., "AIDA Marketing Communication Model: Stimulating a purchase decision in the minds of the consumers through a linear progression of steps," International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research in Social Management, Vol. 1 , 2013, pp 37-44.

- E. St Elmo Lewis, Financial Advertising. (The History of Advertising), USA, Levey Brothers, 1908

- O'Shaughnessy, J., Explaining Buyer Behavior, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992

- Diehl, D. and Terlutter, R., "The Role of Lifestyle and Personality in Explaining Attitude to the Ad," in Branding and Advertising, Flemming Hansen, Lars Bech Christensen (eds), p. 307

- Howard, J.A. Marketing Management, Homewood, Ill. 1963

- Howard, J. A." in: P. E. Earl and S. Kemp (eds.), The Elgar Companion to Consumer Research and Economic Psychology, Cheltenham 1999, pp 310-314.

- Peterson, Arthur F. (1959). Pharmaceutical Selling. Heathcote-Woodbridge.

- Kitson, H.S., Manual for the Study of the Psychology of Advertising and Selling, Philadelphia 1920, p. 21

- Egan, J., Marketing Communications, London, Thomson Learning, pp 42-43

- Bendizlen, M.T., “Advertising Effects and Effectiveness,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 27, No. 10, pp 19-32.

- Vakratsas, D. and Ambler, T., "How Advertising Works: What Do We Really Know?" Journal of Marketing, Vol. 63, No. 1 (Jan., 1999), pp. 26-43 DOI: 10.2307/1251999 URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1251999

- Huey, B., "Advertising's Double Helix: A Proposed New Process Model" Journal of Advertising Research, May/June, 1999, pp 43-51; Belch, G. E. and Belch, M.A., "Evaluating The Effectiveness of Elements of Integrated Marketing Communications: A Review of Research," Occasional Paper, <Online: cbaweb.sdsu.edu>

- Yoon,K., Laczniak, R.N., Muehling, D.D. and Reece, B.B., "A Revised Model of Advertising Processing: Extending the Dual Mediation Hypothesis," Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, Vol. 17, no. 2, 1995, pp 53-67

- Yoon,K., Laczniak, R.N., Muehling, D.D. and Reece, B.B., "A Revised Model of Advertising Processing: Extending the Dual Mediation Hypothesis," Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, Vol. 17, no. 2, 1995, pp 53-67

- Barry, T.E., "The Development of the Hierarchy of Effects: An Historical Perspective," Current Issues and Research in Advertising, vol. 10, no. 2, 1987, pp. 251–295

- Priyanka, R., "AIDA Marketing Communication Model: Stimulating a Purchase Decision in the Minds of the Consumers through a Linear Progression of Steps," International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research in Social Management, Vol. 1 , 2013, pp 37-44.

- Lavidge,R.J. and Steiner, G.A., "A Model for Predictive Measures of Advertising Effectiveness," Journal of Marketing, October, 1961, pp 59-62

- McGuire, W. "An Information Processing Model of Advertising Effectiveness," in Behavioral and Management Science in Marketing, Harry L. Davis and Alvin J. Silk, eds. New York: John Wiley, 1978, pp 156-80.

- Barry, T.E. and Howard, D.J., "A Review and Critique of the Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising," International Journal of Advertising, vol 9, no.2, 1990, pp. 121–135

- Barry, T.E. and Howard, D.J., "A Review and Critique of the Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising," International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 9, no. 2, 1990, pp 121-135

- Wijaya, Bambang Sukma (2012). "The Development of Hierarchy of Effects Model in Advertising", International Research Journal of Business Studies, 5 (1), April–July 2012, p. 73-85

- Barry, T.E. ,The development of the hierarchy of effects: an historical perspective, USA, 1987

- "Catch-Line and Argument," The Book-Keeper, Vol. 15, February 1903, p. 124. Other writings by E. St. Elmo Lewis on advertising principles include "Side Talks about Advertising," The Western Druggist, Vol. 21, February 1899, p. 65-66; Financial Advertising, published by Levey Bros. in 1908; and, "The Duty and Privilege of Advertising a Bank," The Bankers' Magazine, Vol. 78, April 1909, pp. 710–11.

- "Pioneers in the Development of Advertising," Journal of Marketing 12(1), 1947, p. 82

- "St. Elmo Lewis on Modern Publicity Methods," Democrat and Chronicle, January 7, 1910, p. 16.

- London: Effingham Wilson 1854, Sixth Edition, p. 17

- "Well Told is Half Sold," The United Service. A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs, Vol. 9 (N.S.), 1893, p. 8. An identical ad appeared in The Century of the same year.

- "The Bissell Prize Advertisement Contest," Hardware, March 1900, p. 44.

- "Three Natural Fields of Salesmanship," Salesmanship 2(1), January 1904, p. 14.

- C. P. Russell, "How to Write a Sales-Making Letter," Printers' Ink, June 2, 1921

- Sheldon, A., Successful Selling, (Part 1), USA, Kessinger Publishing [Rare Reprint Series], 1911

- Jobber, David; Ellis-Chadwick, Fiona (2013). "1, 15". Principles and Practices of Marketing (7 ed.). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 21, 540. ISBN 9780077140007.

- Diehl, D. and Terlutter, R., "The Role of Lifestyle and Personality in Explaining Attitude to the Ad," in Branding and Advertising, Flemming Hansen, Lars Bech Christensen (eds), p. 307

- Demetrios Vakratsas and Tim Ambler, "How Advertising Works: What Do We Really Know?" Journal of Marketing, Vol. 63, No. 1, 1999, pp. 26-43, DOI: 10.2307/1251999 URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1251999

- O’Shaughnessy, J., Explaining Buyer Behavior, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992

- Egan, J., Marketing Communications, London, Thomson Learning, pp 42-43

- Barry, T.E., "The Development of the Hierarchy of Effects: An Historical Perspective," Current Issues and Research in Advertising vol. 10, no. 2, 1987, pp. 251–295

- J. A. Howard, Marketing Management, Homewood 1963; cf. M. B. Holbrook, "Howard, John A." in: P. E. Earl, S. Kemp (eds.), The Elgar Companion to Consumer Research and Economic Psychology, Cheltenham 1999, pp 310-314.

- Barry, T.E., "The Development of the Hierarchy of Effects: An Historical Perspective," Current Issues and Research in Advertising Vol. 10, no. 2, 1987, pp. 251–295.

- Barry, T.E. and Howard, D.J., "A Review and Critique of the Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising," International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 9, no. 2, 1990, pp 121-135

- Wijaya, Bambang Sukma (2012). “The Development of Hierarchy of Effects Model in Advertising”, International Research Journal of Business Studies, Vol. 5, no 1, 2012, pp 73-85

- Wijaya, Bambang Sukma (2012). "The Development of Hierarchy of Effects Model in Advertising", International Research Journal of Business Studies, 5 (1), April–July 2012, p. 73-85

- Christian Betancur, El vendedor Halcón: sus estrategias. El poder de la venta consultiva para ganar más clientes satisfechos, Medellín, Colombia, 2nd ed., 2014, ICONTEC International, ISBN 978-958-4643513 www.elvendedorhalcon.com

- Rossiter, J.R. and Percy, L.,"Advertising Communication Models", in: Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 12, Elizabeth C. Hirschman and Moris B. Holbrook (eds), Provo, UT : Association for Consumer Research, 1985, pp 510-524., Online: http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/6443/volumes/v12/NA-12 or http://www.acrwebsite.org/search/view-conference-proceedings.aspx?Id=6443

References

External links

Media related to AIDA (marketing) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to AIDA (marketing) at Wikimedia Commons