63rd Drive–Rego Park station

The 63rd Drive–Rego Park station is a local station on the IND Queens Boulevard Line of the New York City Subway, consisting of four tracks. Located at 63rd Drive and Queens Boulevard in the Rego Park neighborhood of Queens, it is served by the R train at all times except nights, and the E and F trains at night.

63 Drive–Rego Park | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

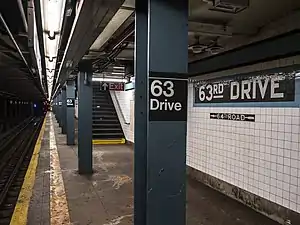

View of northbound platform | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Address | 63rd Drive & Queens Boulevard Rego Park, NY 11374 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borough | Queens | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Rego Park | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40.73°N 73.862°W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Division | B (IND)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | IND Queens Boulevard Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | E F R | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Structure | Underground | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 2 side platforms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | December 31, 1936 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opposite- direction transfer | Yes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former/other names | 63rd Drive | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traffic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019 | 4,753,706[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | 95 out of 424[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

The Queens Boulevard Line was one of the first lines built by the city-owned Independent Subway System (IND),[3][4][5] and stretches between the IND Eighth Avenue Line in Manhattan and 179th Street and Hillside Avenue in Jamaica, Queens.[3][5][6] The Queens Boulevard Line was in part financed by a Public Works Administration (PWA) loan and grant of $25 million.[7] In 1934 and 1935, construction of the extension to Jamaica was suspended for 15 months and was halted by strikes.[8] Construction was further delayed due to a strike in 1935, instigated by electricians opposing wages paid by the General Railway Signal Company.[9] By August 1935, work had resumed on the 67th Avenue station and three other stations on the Queens Boulevard Line.[10]

On December 31, 1936, the IND Queens Boulevard Line was extended by eight stops, and 3.5 miles (5.6 km), from its previous terminus at Roosevelt Avenue to Union Turnpike, and the 63rd Drive station opened as part of this extension.[11][12][13] The E train, which initially served all stops on the new extension, began making express stops in April 1937,[14] and local GG trains began serving the extension at the time.[15]

Station layout

| Ground | Street level | Exit/entrance |

| Mezzanine | Fare control, station agent, MetroCard machines | |

| Platform level | Side platform | |

| Southbound local | ← ← ← | |

| Southbound express | ← | |

| Northbound express | | |

| Northbound local | | |

| Side platform | ||

There are four tracks and two side platforms;[16] the two center express tracks are used by the E and F trains at all times except late nights.[17] The E and F trains serve the station at night,[18][19] and the R train serves the station at all times except late nights. [20] The station is between Woodhaven Boulevard to the west and 67th Avenue to the east.[21]

Both platforms have a blue tile band with a black border and mosaic name tablets reading "63RD DRIVE" in white sans-serif lettering on a black background and matching blue border. A few of these tablets have modern metal signs above them reading "Rego Park". Small tile captions reading "63RD DRIVE" in white lettering on black run below the tile band, and directional signs in the same style are present below some of the name tablets. The tile band was part of a color-coded tile system used throughout the IND.[22] The tile colors were designed to facilitate navigation for travelers going away from Lower Manhattan. As such, the blue tiles used at the 63rd Drive station are also used at Jackson Heights–Roosevelt Avenue, the next express station to the west, while a different tile color is used at Forest Hills–71st Avenue, the next express station to the east. Blue tiles are similarly used at the other local stations between Roosevelt Avenue and 71st Avenue.[23][24]

Dark slate blue I-beam columns run along both platforms at regular intervals, alternating ones having the standard black station name plate with white lettering. The I-beam piers are located every 15 feet (4.6 m) and support girders above the platforms. The roof girders are also connected to columns in the walls adjoining each platform.[25]: 3 This station has an upper level mezzanine that is about one-third the length of the platforms. The mezzanine is split into three sections by a wall on the southbound side and a chain link fence on the northbound side. Numerous staircases from each platform go up to their respective outer section of the mezzanine. A small turnstile bank on the southbound side and exit-only turnstiles on the northbound side lead to the main fare control area.

The tunnel is covered by a "U"-shaped trough that contains utility pipes and wires. The outer walls of this trough are composed of columns, spaced approximately every 5 feet (1.5 m) with concrete infill between them. There is a 1-inch (25 mm) gap between the tunnel wall and the platform wall, which is made of 4-inch (100 mm)-thick brick covered over by a tiled finish. The columns between the tracks are also spaced every 5 feet (1.5 m), with no infill.[25]: 3

Exits

Towards the northwest end of the mezzanine, a single extra-wide staircase from each platform goes up to a crossover, where a turnstile bank leads to the main fare control area. There is a token booth and two street stairs, one to the northwest corner of 63rd Drive and Queens Boulevard and the other to the south side of Queens Boulevard near this intersection.[26]

On the southeast side of the mezzanine, high entry-exit turnstiles from either outer section lead to an un-staffed fare control area, where one street stair goes up to the northwest corner of 64th Avenue and Queens Boulevard while the other goes up to the south side of Queens Boulevard near the intersection with 64th Road. The mezzanine has mosaic directional signs in white lettering on a teal border. The center section connects the two fare control areas, but provides no crossover.[26]

On the extreme northwest (railroad south) end of the platforms, high turnstiles lead to a single staircase that goes up to either western corners of 63rd Road and Queens Boulevard, the northwest one for the Manhattan-bound platform and the southwest one for the Forest Hills-bound platform.[26] Prior to 2010, these entry points were exit-only.[27] They were made entrances to accommodate traffic from the expansion of Rego Center.

Unfinished Rockaway spur

East of this station, there is an unfinished signal tower on the Jamaica-bound (railroad north) platform and a bellmouth that diverges to the south from the local track. Another tunnel from the Manhattan-bound local track diverges north, then curves south under the Queens Boulevard Line to join the other bellmouth.[28] These were provisions for a planned expansion in the 1930s that would have connected with the IND Rockaway Line (formerly a Long Island Rail Road branch) towards Howard Beach, JFK Airport, and the Rockaways.[29][30][31][32][33] This spur would have run down 66th Avenue before joining the Rockaway Line at its former junction with the LIRR Main Line.[31] In January 2013, a petition was started on change.org to make use of the bellmouths to connect the station to the currently unused portion of the Rockaway Line.[34]

References

- "Glossary". Second Avenue Subway Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement (SDEIS) (PDF). Vol. 1. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. March 4, 2003. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- "Facts and Figures: Annual Subway Ridership 2014–2019". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Duffus, R.L. (September 22, 1929). "OUR GREAT SUBWAY NETWORK SPREADS WIDER; New Plans of Board of Transportation Involve the Building of More Than One Hundred Miles of Additional Rapid Transit Routes for New York". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- "QUEENS SUBWAY WORK AHEAD OF SCHEDULE: Completion Will Lead to Big Apartrnent Building, Says William C. Speers". The New York Times. April 7, 1929. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "Queens Lauded as Best Boro By Chamber Chief". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 23, 1929. p. 40. Retrieved October 4, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "New Subway Routes in Hylan Program to Cost $186,046,000" (PDF). The New York Times. March 21, 1925. p. 1.

- "TEST TRAINS RUNNING IN QUEENS SUBWAY; Switch and Signal Equipment of New Independent Line Is Being Checked". The New York Times. December 20, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- Neufeld, Ernest (August 23, 1936). "Men Toil Under Earth to Build Subway" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. p. 2 (Section 2). Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- See:

- "500 More Quit Subway Work On Boulevard: General Strike Order Issued Today; 72 Walk Out in Jamaica" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. April 2, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- "Aldermen Probe Strike on Subway" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. April 3, 1935. p. 4. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- "Work Progressing on Queens Subway". The New York Times. August 11, 1935. p. RE2. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 101425888.

- Roger P. Roess; Gene Sansone (August 23, 2012). The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-3-642-30484-2.

- "City Subway Opens Queens Link Today; Extension Brings Kew Gardens Within 36 Minutes of 42d St. on Frequent Trains". The New York Times. December 31, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Mayor Takes 2,000 for a Ride ln Queens Subway Extension: Heads Civic Leaders in 10-Car Train Over Route to Kew Gardens That Opens at 7 A. M. Today; Warns of 15-Cent Fare if Unity Plan Fails The Mayor Brings Rapid Transit to Kew Gardens". New York Herald Tribune. December 31, 1936. p. 34. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1222323973.

- "Trains Testing Jamaica Link Of City Subway". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 10, 1937. p. 3. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- "Jamaica Will Greet Subway" (PDF). The New York Sun. April 23, 1937. p. 8. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- Dougherty, Peter (2006) [2002]. Tracks of the New York City Subway 2006 (3rd ed.). Dougherty. OCLC 49777633 – via Google Books.

- "Late Night Subway Service" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. March 23, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- "E Subway Timetable, Effective December 4, 2022". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- "F Subway Timetable, Effective August 28, 2023". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- "R Subway Timetable, Effective August 28, 2023". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- "Tile Colors a Guide in the New Subway; Decoration Scheme Changes at Each Express Stop to Tell Riders Where They Are". The New York Times. August 22, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Carlson, Jen (February 18, 2016). "Map: These Color Tiles In The Subway System Used To Mean Something". Gothamist. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- Gleason, Will (February 18, 2016). "The hidden meaning behind the New York subway's colored tiles". Time Out New York. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- "New York MPS Elmhurst Avenue Subway Station (IND)". Records of the National Park Service, 1785 - 2006, Series: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013 - 2017, Box: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: New York, ID: 05000672. National Archives.

- "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Forest Hills" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- Google (July 21, 2021). "96-5 New York 25 Service, New York" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- "Tomb Ov The Unknown Tunnel". ltvsquad.com. January 21, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- "The Express Stop That Never Was". ltvsquad.com. LTV Squad. June 2, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- Kihss, Peter (April 13, 1967). "3 Routes Proposed to Aid Growing Queens Areas" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- "City Plans to Buy New Subway Link: Would Take Over Rockaway Branch of Long Island to Connect With Queens" (PDF). The New York Times. December 23, 1933. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- "Complete Text of TA's Queens Subway Plan". Long Island Star-Journal. Fultonhistory.com. April 1, 1963. p. 8. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- Perlow, Austin H. (March 15, 1957). "New Rockaway Link Possible at Bargain Price". Long Island Star-Journal. Fultonhistory.com. p. 6. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Capt. Subway (January 21, 2013). "Guest Post: How sending the R train to Howard Beach can help the G go to Forest Hills". Cap'n Transit Rides Again Blog. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

External links

- nycsubway.org – IND Queens Boulevard Line: 63rd Drive/Rego Park

- nycsubway.org – The History of the Independent Subway:

- Station Reporter — R Train

- Station Reporter — M Train

- Forgotten NY: Subways and Trains — Rockaway Branch

- Forgotten NY: Subways and Trains — Subway Signs to Nowhere

- The Subway Nut - 63rd Drive–Rego Park Pictures Archived January 5, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- 63rd Road exit only stair from Google Maps Street View

- 63rd Drive entrance from Google Maps Street View

- 64th Road entrance from Google Maps Street View

- Platforms from Google Maps Street View