2011 IZOD IndyCar World Championship

The 2011 IZOD IndyCar World Championship was the scheduled final race of the 2011 IZOD IndyCar series. It was to be run at Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Vegas, Nevada USA on October 16, 2011, and was scheduled for 200 laps around the facility's 1.544 mile oval.

| Race details | |

|---|---|

| 18th round of the 2011 IndyCar Series season | |

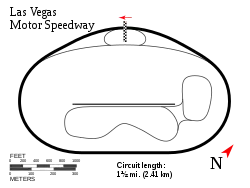

The layout of Las Vegas Motor Speedway, where the race was held | |

| Date | October 16, 2011 |

| Official name | IZOD IndyCar World Championship |

| Location | Las Vegas Motor Speedway Clark County, Nevada, U.S. |

| Course | Oval 1.544 mi / 2.485 km |

| Distance | 12 laps 18.528 mi / 29.817 km |

| Scheduled Distance | 200 laps 308.800 mi / 496.965 km |

| Weather | Temperatures reaching up to 93.9 °F (34.4 °C); wind speeds up to 17.1 miles per hour (27.5 km/h)[1] |

| Pole position | |

| Driver | Tony Kanaan (KV Racing Technology) |

| Time | 50.0582, 222.078 mph (357.400 km/h) |

| Podium | |

| First | Tony Kanaan (KV Racing Technology) |

| Second | Ed Carpenter (Sarah Fisher Racing) |

| Third | Ryan Briscoe (Team Penske) |

The race, however, was cancelled after only 12 laps had been run. Contact between drivers Wade Cunningham and James Hinchcliffe triggered a massive chain reaction crash that involved fifteen of the thirty-four entrants in the event and resulted in the death of former IndyCar Series champion Dan Wheldon.[2][3] Open wheel racing has not returned to the circuit since the incident.

Report

Background

The Las Vegas race was added to the schedule for the 2011 season,[4] replacing the event at Homestead-Miami Speedway as the final race of the IndyCar season. The races at Homestead and the International Speedway Corporation tracks were removed from the schedule following the previous year's season. Las Vegas Motor Speedway was returning to the IndyCar schedule for the first time since 2000,[4] and the event marked the first open-wheel race at the circuit since the Hurricane Relief 400 Champ Car event in 2005.[4] The circuit since was reconfigured in 2006, which saw a greater degree of banking added to the circuit to encourage side-by-side racing.[4][5] The race was scheduled for 200 laps around the 1.544 mi (2.485 km) oval, totaling 308.800 mi (496.965 km).

This was the final entry for Vítor Meira, Paul Tracy, Tomas Scheckter, Buddy Rice, and Davey Hamilton, and Dan Wheldon.

This would also be the final entry for Danica Patrick until 2018, where she would participate in the Indy 500 to conclude her racing career.

Media coverage

ABC broadcast the race on American television. Marty Reid was the lead commentator with Scott Goodyear and Eddie Cheever as analysts. Vince Welch, Jamie Little, and Rick DeBruhl were the pit reporters.[6]

The IMS Radio Network provided the radio coverage with Mike King on lead. Josef Newgarden, who had run the Indy Lights series event earlier in the day and had been crowned that series’ champion for 2011, was the booth analyst; Davey Hamilton, who normally occupied that role, entered the event in a car fielded by Dreyer & Reinbold Racing. Mark Jaynes reported from Turn 3, and Jake Query and Kevin Lee served as the pit reporters.

The $5 Million Challenge

On February 22, 2011, IndyCar CEO Randy Bernard announced that a $5,000,000 (USD) purse would be awarded to any driver not on the IndyCar circuit to enter the race at Las Vegas and win while starting from the back of the field.[7][8] Bernard's original offer was exclusively to "any race car driver in the world outside of the IZOD IndyCar Series,"[4] hoping to attract interest from Formula 1 or NASCAR.[9][8] Bernard received offers that he deemed viable from motocross racer Travis Pastrana, former IndyCar champion Alex Zanardi, and NASCAR's Kasey Kahne, but all three offers were not without issue.[10]

Pastrana, who also drove rally cars and would eventually compete in NASCAR, had entered the Best Trick event at X Games XVII in Los Angeles in July 2011. During his attempt at a rodeo 720, Pastrana crashed on landing and broke his foot and ankle. He was still working to rehabilitate the injury, and would likely have required special controls to be put in the car if he was to attempt the feat.

Zanardi's problem was twofold. He had not competed in an IndyCar event since the 2001 American Memorial at EuroSpeedway Lausitz, during which both of his legs were severed on impact after Alex Tagliani hit his car after Zanardi, who had been exiting out road, lost control of his vehicle. Zanardi also requested to drive for his former team, Chip Ganassi Racing, and they were unable to fulfill his request due to a lack of available resources. Kahne also had this problem, as he desired to drive for Team Penske.[10] In his case, cross-country travel would cause a logistical issue; NASCAR would be running the Bank of America 500 at Lowe's Motor Speedway the night before IndyCar's event.

Bernard later revised the challenge to include a driver who had only competed in IndyCar part-time during the 2011 season; the challenge was accepted by 2011 Indianapolis 500 winner Dan Wheldon, who had run only one additional race that season: the Kentucky Indy 300, in which Wheldon also started at the back of the field in the No. 77 Sam Schmidt car, and finished 14th.[10] Wheldon agreed to split the purse with a fan if he went on to win.[10]

Championship battle

Entering the race, the only two drivers still in contention for the IndyCar Championship were Ganassi's Franchitti and Penske's Power. Franchitti was 18 points ahead of Power, retaking the championship points lead from him with a second-place finish at the 2011 Kentucky Indy 300 two weeks prior. Power was still mathematically in the points race despite an awful finish at Kentucky, but needed to finish far ahead of Franchitti in order to win the championship title.[11]

The race's honorary grand marshal was skateboarder Tony Hawk, who gave the command to start the engines.[12]

Qualifying

A total of thirty-four cars qualified for the race. Tony Kanaan, driving the No. 82 Dallara for KV Racing Technology, qualified on the pole for the race and shared the front row with Oriol Servià, driving the No. 2 Dallara for Newman/Haas Racing. Danica Patrick, driving the No. 7 Dallara for Andretti Autosport, started 9th in what was her final IndyCar start before joining NASCAR.[13] The two remaining championship contenders qualified on row 9, with Power 17th in the No. 12 Dallara and Franchitti 18th in the No. 10 Dallara.[14] In addition to Wheldon's No. 77 Dallara, which he piloted for Sam Schmidt Motorsports, Buddy Rice was forced to start from the rear of the field when he received a penalty in qualifying for driving the No. 44 Dallara below the track's white line.[8]

Lap 11 crash – Death of Dan Wheldon

The accident began on the front straightaway as the field headed into turn one. Wade Cunningham, Wheldon's teammate in No. 17, clipped James Hinchcliffe, driving No. 06,[15] and then made contact with J. R. Hildebrand in No. 4. Then Cunningham swerved and Hildebrand drove over the rear of his car, causing his to go airborne. Cunningham collected Jay Howard in No. 15 on the inside and then Townsend Bell in No. 22 on the outside before colliding with the retaining wall. Attempting to avoid the crash ahead, Vítor Meira lost control of his No. 14 and spun inward, collecting both Charlie Kimball's No. 83 and E. J. Viso's No. 59. Tomas Scheckter, in No. 57, was also attempting to avoid the crash by rapidly slowing down on the outside. Following that, Paul Tracy ran into the back of his car with his No. 8 and Pippa Mann, rapidly approaching in No. 30, went over the top of him after jerking to the outside to avoid crashing into Alex Lloyd in No. 19.[16]

As cars continued to drive through the accident scene, the No. 77 car driven by Wheldon and the No. 12 driven by Power left the racing surface. Wheldon was racing at 220 miles per hour (350 km/h) when he came upon the scene, frantically trying to avoid the collision. Although he was able to considerably slow it down, Wheldon's car went airborne about 325 feet (99 m) after running into the back of Kimball's and went barrel-rolling into the catch fence cockpit-first, causing his head to hit one of the poles. The No. 77 landed back on the racing surface having been sliced apart by the fence and slid to a stop next to the SAFER barrier.[17] Meanwhile, Power went airborne when he ran over the back of Lloyd's car and struck the SAFER barrier. The car landed sideways on the track and rolled over, which caused the front wheel assembly to break; one of the front tires flew over Power's head and barely missed hitting him.[18]

"The debris we all had to drive through the lap later, it looked like a war scene from [The] Terminator or something. I mean, there were just pieces of metal and car on fire in the middle of the track with no car attached to it and just debris everywhere."

Ryan Briscoe's reaction to driving through the scene of the accident, one lap after the collision.[19]

A total of 15 cars were involved, with the most severe injuries suffered by Wheldon, Power, Hildebrand, and Mann.[20] Wheldon was extricated from his car and was airlifted to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada. He was officially pronounced dead on arrival two hours later at 1:54 pm Pacific Daylight Time. The official cause of Wheldon's death was given by the Clark County Coroner as blunt force trauma to his head due to the incident.[21] Mann and Hildebrand were later taken to the hospital for overnight observation, while Power was evaluated and released that day.[20]

IndyCar officials stopped the proceedings one lap later and put the race under a red flag. The nineteen cars that were still running were called to their pit boxes, and work began on the cleanup. The damage caused by the crash was significant. The catch fence had been damaged where the #77 had made contact with it and would need to be repaired before racing resumed. In addition, as some of the drivers drove through the scene during the brief caution period, they reported massive amounts of debris that they could not avoid driving over and that the asphalt surface had received several gashes in it that would need to be patched. With all of the work that needed to be done, there would be a significant delay in resuming the race. The only thing left to be determined would be to see who would win the race. Power's involvement in the incident had resulted in Franchitti clinching the points championship, and with Wheldon also out of the race, since no other driver had taken the $5,000,000 challenge, there would be no prize awarded.[18]

Still, IndyCar officials elected to keep the race under red flag conditions as they worked on a solution. The delay extended for nearly three hours, and tension began to mount over both the status of the race and the condition of Wheldon, as there had been no updates since the accident. During the lengthy delay, ESPN conducted interviews with several drivers, who expressed their growing concern for their fellow competitor, as well as team owner Michael Andretti, who took it upon himself to head to the trailer on pit road where the officials were located. He would be turned away by the officials and return with no further information.[18]

At approximately 3:00 pm PST, IndyCar Series director Brian Barnhart called for all race team personnel to report to the infield media center for a meeting that was closed to reporters. The ABC broadcast was able to capture video of the drivers and team personnel as they exited the media center, and their expressions as they left were grim. Tony Kanaan, the race polesitter and a former teammate of Wheldon's from their days driving for Andretti's race team, was shown sobbing as he returned to his pit box.

"IndyCar is very sad to announce that Dan Wheldon has passed away from unsurvivable injuries. Our thoughts and prayers are with his family today. IndyCar, its drivers and team owners, has decided to end the race. In honor of Dan Wheldon, the drivers have decided to do a five-lap salute in his honor. It will take place in approximately 10 minutes. Thank you."

Randy Bernard, announcing the confirmation of Wheldon's death to the media.[22]

As the meeting ended, Randy Bernard called a press conference. There, he gave a brief statement where he informed the media that Wheldon had died of his injuries suffered in the accident. He then announced that the remainder of the race was cancelled and that the drivers would be returning to the track for what he referred to as a "five lap salute" to honor their fallen competitor, then left without taking any questions. ABC cut into the press conference late and missed Bernard's initial statement, which left Marty Reid to break the news to the viewing audience.[18]

Meanwhile, the scoring tower was blanked except for the number 77, which was displayed in the first-place position. With Kanaan, Ed Carpenter, and Ryan Briscoe leading, eighteen of the nineteen cars that were still running when the accident happened lined up on pit road in six rows of three, akin to the starting formation for the Indianapolis 500. The only car that did not take part in the salute was Bryan Herta Autosport's car, which Wheldon drove to victory at Indianapolis earlier in 2011 but was driven that day by Alex Tagliani.[18]

The safety car then led the cars back onto the track while every crew member and person behind the wall moved to the grass separating pit road from the track to watch.[23][24] The track loudspeakers played bagpipe renditions of "Danny Boy" and "Amazing Grace" while the cars went around the track at pace lap speed, and each time the cars passed the start/finish line the fans remaining in the front-stretch grandstand offered applause. At the end of the five tribute laps, the starter waved two checkered flags to signify the end while the cars proceeded around the track one more time before exiting for the pits in turn four.[20][23]

Wheldon's death was the first suffered by an IndyCar driver since Paul Dana was killed in a race-morning practice crash at Homestead-Miami in 2006.[22]

Championship resolution

As noted above, the accident on lap 11 ended the championship points battle and would have clinched the season championship for Franchitti regardless of the results of the race. Since the event did not reach IndyCar standards for an official race, meaning it did not pass the halfway mark before it was abandoned, none of the drivers involved were awarded points and the driver point totals entering the race stood as the final totals for the season.

This was Franchitti's third consecutive[23] and fourth overall championship, and fourth consecutive championship for Chip Ganassi Racing (equaling a feat achieved in CART from 1996 to 1999).[17] Indy Racing League, LLC. delayed all official prize-giving, choosing instead to conduct it during the annual State of IndyCar speech in February 2012; Franchitti also delayed his own celebration of his championship victory.

Reactions

At the time of his death, Wheldon had been working with IndyCar officials to develop the ICONIC chassis with the intention of improving safety in the sport.[25] Planned changes to the chassis include larger cockpits for driver protection and bodywork over the rear wheels to prevent cars from launching off one another in the event of a collision, long a problem in open-wheel racing, regardless of oval or road course, but troublesome on high-speed ovals and tight street circuits with a long straight and a tight turn, similar to the style of many modern road courses.[26]

Prominent figures within the IndyCar fraternity and the wider international motorsport community expressed their condolences to Wheldon and his family.[27] Wheldon had been scheduled to take part in the Gold Coast 600, a round of the V8 Supercars championship, on October 22, racing alongside his friend James Courtney. Upon hearing of Wheldon's death, Courtney described the accident as a sobering reminder of the dangers faced by racing drivers.[28] As the first major international motorsport event after Wheldon's death, organizers of the V8 Supercars series planned a series of tributes to him at the Gold Coast 600.[29] Wheldon's place was taken by another British driver, Darren Turner, an FIA GT1 World Championship competitor. Wheldon's name was left on the car as a mark of respect,[30] while British drivers at the event paid tribute to him with helmet decals, and several other drivers planned individual tributes to Wheldon.[31] Kanaan, who had also been scheduled to race in Australia, announced his withdrawal from the event out of respect for Wheldon. However, Briscoe, Tagliani, and Hélio Castroneves, all of whom raced at Las Vegas, along with other part-time IndyCar drivers Sébastien Bourdais and Simon Pagenaud, who were not at Las Vegas, did race.[32] Bourdais, the best performing "International" driver, received the Dan Wheldon Memorial Trophy. Sam Schmidt, for whom Wheldon had been racing at the time of his accident, admitted that the events at Las Vegas Motor Speedway had prompted him to re-evaluate his involvement in motorsports.[33] Similarly, veteran drivers Davey Hamilton and Paul Tracy said they were considering retiring from racing on the back of the accident.[33][34]

"I could see within five laps [that] people were starting to do crazy stuff. I love hard racing, but that to me is not really what it's about. One small mistake from somebody [...] right now I'm numb and speechless. One minute you're joking around in driver intros and the next he's gone. He was six years old when I first met him. I told his son Thursday night at the parade on The Strip that I’ve known his dad since he was about your size. And then I talked to a friend of mine, Jesse Spence, that I used to race go-karts with that we’ve known him since he was this little kid. His mouth worked plenty good, but he was just this little kid and the next thing you know he was my teammate in IndyCars. We put so much pressure on ourselves to win races and championships, it’s what we love to do, it’s what we live for, and then on days like today it doesn’t really matter. Everybody in the IndyCar Series was Dan's friend."

Dario Franchitti, describing his feelings in the aftermath of the accident.[23]

In the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series, several drivers at the 2011 Good Sam Club 500 at Talladega on the weekend after Wheldon's death put special tributes on their cars, like NASCAR issuing the "Lionheart Knight" decal Wheldon wore on his helmet,[35] which were placed on the cars' b-pillars,[36] along with T. J. Bell putting Wheldon's name on the namerail.[37]

Driver Marco Andretti withdrew from The Celebrity Apprentice, which started taping days after the incident, and was replaced by his father Michael, team principal of Andretti Autosport.[38]

On December 9, 2011, IndyCar decided that they were not going to return to Las Vegas for the 2012 season.[39] Randy Bernard expressed reluctance to return to the speedway following Wheldon's death, despite the insistence of Speedway Motorsports, Inc. president Bruton Smith (who owns the track in Las Vegas as well as three other tracks used by the IndyCar series) for the series to honor its three-year contract with the track. As of that date, the investigation into the accident was still ongoing. IndyCar was holding back on the release of its 2012 schedule until the investigation concluded. The IndyCar series also conducted an investigation into whether or not the series should continue racing on high-banked ovals such as Las Vegas and Texas Motor Speedway in Denton, Texas. Texas had been one of the staples of the IndyCar series since 1997 and had yet to be confirmed for 2012 prior to the Las Vegas race in 2011. Indycar's future at high-banked ovals was in jeopardy pending the results of the investigation.[40] Texas was eventually placed on the 2012 schedule.[38]

The series went to new restrictions on restarts. IndyCar announced that restarts would only be single-file in 2012, rather than double-file as they had been the previous season.[41]

Criticism

"A lot of things that happened in this race they are hoping would not happen with these changes. Maybe the scale has tipped a little bit too far to make it more entertaining. They would serve themselves well if they listened to the drivers a little bit more ... and the concerns they voiced."

ABC commentator and former driver Eddie Cheever's criticism of series officials' renewed focus on entertainment.[26]

In the build-up to the event, several drivers expressed unease at the race – with Franchitti, Oriol Servià and Alex Lloyd the most vocal opponents – particularly given the high degree of banking around the circuit,[26] with between 18 and 20 degrees of banking in the corners. Franchitti was quoted as saying that the track was "not suitable" for IndyCar racing,[42] while championship rival Will Power described the race as "an accident waiting to happen".[43]

The field of 34 drivers was the biggest in an IndyCar series race since the 1997 Indianapolis 500. A typical oval track race has six to eight fewer drivers, except for the Indianapolis 500, which normally has a 33-car field (but is run at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which is two and a half miles in distance with a maximum banking of 9.2 degrees, as opposed to Las Vegas which is one and a half miles in distance and has banking up to 20 degrees).[44] ESPN.com senior motorsports writer Terry Blount wrote: "Obviously more cars presents more danger. They wanted a whole lot of cars cause obviously this is their season finale and they wanted it to be a big deal. Some of the people that were driving in this event yesterday had no business being in it. Some of them had never driven on a track like this. That was a mistake".[42] Chris Powell, president of Las Vegas Motor Speedway, defended the race, saying that the circuit had passed all of the IndyCar Series' accreditation procedures and was deemed suitable for racing. He also went on the record to say that despite the media reporting the concerns of several drivers over the safety of the event, none of those concerns had been raised with him.[45]

1979 Formula One World Champion Jody Scheckter, whose son Tomas was involved in the accident, was highly critical of the series organizers, stating that a serious accident was "inevitable" as "they were basically touching wheels at 220 mph (350 km/h). They all bunch up together so there are thirty-four cars in a small space of track. One person makes a mistake and this happens. You [shouldn't] have to get killed if you make a mistake. It was madness."[46] Former Formula One and IndyCar driver Mark Blundell agreed, claiming that the Las Vegas circuit was unsuitable for IndyCar racing – this was the last race for the Dallara IR05 – while NASCAR Sprint Cup Series champion Jimmie Johnson called for the series to leave oval racing altogether,[47] though he clarified his statement by saying that the open-wheel type cars on a resurfaced 1.5 mi (2.4 km) track built for the heavier Sprint Cup and Nationwide Series cars was a bad idea (the circuit was reconfigured from 12 degrees to the 18-20 degree banking in 2006; ten years later, Johnson took the Rookie Orientation Program for the 2022 Indianapolis 500.[48] However, former champion Mario Andretti said that the accident was a "freakish" one-off incident and that facilities at the circuit were adequate for racing.[49] While he admitted surprise that more drivers were not seriously injured, he also cautioned against what he called "knee-jerk reactions" to the accident, calling for any changes to the sport to be carefully considered before being introduced, rather than being rushed into action. Former Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) President Max Mosley, a long-time advocate of increased safety in motorsport, agreed with Andretti, urging a "calm and scientific" approach to any proposed changes,[50] particularly when asked about the proposed introduction of closed canopies for open-wheel racing cars.[51]

The five million dollar prize was also the subject of criticism in that a driver inexperienced in driving IndyCars would have a higher risk of causing a crash,[5] though Formula One driver Anthony Davidson downplayed the influence of the prize in causing the accident, stating that racing drivers by their nature try to win every race, whether they start from first or last.[46]

In the days following the incident, it was learned that at least three additional drivers had been approached to try for the $5 million challenge prize. One was Scott Speed, who previously ran open-wheel Formula One cars for Scuderia Toro Rosso and who had raced on the reconfigured LVMS track in the Craftsman Truck Series for Morgan-Dollar Motorsports in 2008 and for Team Red Bull in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series in 2009 and 2010. Speed, in an interview he gave to Inside Edition on October 18, 2011, said that he declined to take the offer saying that the track conditions were too dangerous for Indy-type cars.[52] Likewise, A. J. Allmendinger, who also had previous open-wheel experience, had expressed early interest,[53] though he later declined, recalling, "[When] we raced CART at Vegas...it scared the living hell out of me."[54] Finnish media reported that 2007 Formula One World Champion Kimi Räikkönen, who was splitting time between the World Rally Championship and NASCAR in 2011, had also been approached to take part in the race, but Räikkönen rejected the offer as he was not confident of having a competitive car, rather than having concerns over safety.[55]

Investigation

"The chassis of the [Wheldon's] #77 impacted a post along the right-side of the tub and created a deep defect in the tub that extended from the pedal bulkhead, along the upper border of the tub, and through the cockpit. As the race car passed by, the pole intruded into the cockpit and made contact with the drivers' helmet and head. Dan's injury was limited to his head injury. Dan appeared to suffer two distinct head forces. The first head force created a level of Head Injury Criterion, also known as a HIC number, that normally does not produce any injury. During the initial crash sequence, the accident data recorder measured 12 or 13 impacts. During that timeframe one of those impacts measured a measurable HIC number for Dan – that's the number that does not normally cause injury. The number was low enough. The second force was a physical impact, and it was the second force that caused a non-survivable blunt force injury trauma to Dan's head."

Brian Barnhart, detailing the sequence of events surrounding the accident in the official report on Wheldon's death.[56]

Three days after the accident, series organizers announced that the race would be the subject of a full investigation. The other members of the Automobile Competition Committee for the United States (ACCUS), the national governing body of automobile racing in the United States, and a member of the FIA made their resources available for the investigation, which IndyCar officials expected to take several weeks.[57] As all ACCUS/FIA members participated in the investigation, IndyCar would have full use of the NASCAR R&D Center in Concord, North Carolina. In the meantime, all testing at Las Vegas Motor Speedway was cancelled indefinitely; Franchitti and Chip Ganassi Racing had been planning to test the 2012-spec Dallara chassis at the circuit in the week following the race.[57]

Results

The results of the investigation into Wheldon's death were released on December 15, 2011. In a report prepared by crash investigators, it was found that Wheldon's death was caused by an impact with the catch fencing around the circuit.[56] Brian Barnhart further rejected claims that the banking had also contributed to the accident,[58] stating that it created two ideal racing lines, and that these lines made the location of cars more predictable for other drivers; at the time of the accident, all 34 cars had been behaving as expected. The report also revealed that the right front pull rod of the suspension assembly penetrated Wheldon's survival cell, though it did not cause him any injury. The report recommended further investigation of this phenomenon, as it was the first recorded incident of its kind in nine years of the use of the IR03 and later IR05 model chassis, which was being retired at the end of the race. The pull-rod suspension chassis is not being utilised in the DW12,[59] however, a similar penetration in a DW12 would later cause significant injury to James Hinchcliffe during practice for the 2015 Indianapolis 500.[60]

Legacy

Since Wheldon's death at the Las Vegas oval, much emphasis has been put into the elimination of "pack racing" through changes to the tires and downforce levels on high-banked ovals (particularly at Texas Motor Speedway, for its annual IndyCar event). Such racing has been seen on occasion since the Vegas race, most notably at the 2015 MAVTV 500 at Auto Club Speedway (which ended with contact entering the final lap that sent Ryan Briscoe, subbing for Hinchcliffe, airborne),[61] and the 2017 Rainguard Water Sealers 600 at Texas, where "pack racing" again reappeared (the latter event also featured a NASCAR phenomenon known as "The Big One") and only a handful of drivers finished the race, although none were seriously injured.[62] However, for the most part the league has avoided pack races in the years since the 2011 Finale.

Talk of a canopy or halo to protect the driver was accelerated by the fatal Formula One accident that killed Jules Bianchi in October 2014 and an incident where Justin Wilson was fatally struck in the head by debris at the August 2015 ABC Supply 500 at Pocono Raceway.[63] In particular, following Wilson's death, Allmendinger stated that he would "never again" run open-wheel cars, adding "The only way I would do it is if they put in a closed cockpit over the car and tested it and they thought that was a good direction in safety then I might think about doing it again."[64] As a result, several major open-wheel series have implemented cockpit protection systems, with Formula One,[65] Formula Two,[66] Formula Three[67] and Formula E[68] all introducing the halo in 2018, and IndyCar instituting the Aeroscreen in 2020.[69]

The rear wheel pods introduced to IndyCar in 2012 intended to prevent cars from becoming airborne when hitting another in the rear proved to be ineffective as there were major crashes resulting from such contact, including Dario Franchitti's career-ending crash during the 2013 race in Houston,[70] as well as the 2017 Indianapolis 500 involving Scott Dixon.[71] In addition the pods were often ripped from cars from light contact, placing hazardous debris on the track. As a result, the rear pods were eliminated for 2018.[72][73]

In March 2016, during the Kobalt 400 NASCAR weekend, Fox Sports reporter Jamie Little, who was on the ESPN broadcast and drove to University Medical Center as part of post-crash coverage, and Wheldon's close friend Brent Brush placed a memorial plaque at the site Wheldon's car impacted the catch fencing post.[74] For the 2022 NASCAR October weekend as Las Vegas, Nick Yeoman, an INDYCAR Radio broadcaster, worked the PRN broadcast in Turn 2 near near the Wheldon plaque. Yeoman posted on Twitter, "Here’s to remembering legends and creating better memories on October 16th," while showing the Wheldon memorial and his broadcast position.[75]

INDYCAR returned to the Las Vegas Motor Speedway slightly over a decade later in January 2022 with the Indy Autonomous Challenge, held as part of the Consumer Electronics Show, using Indy NXT Dallara spec chassis modified for the challenge. The race was repeated in 2023. The PoliMOVE team of Politecnico di Milano and the University of Alabama has won both events.[76] Speeds reached 180 MPH in the 2023 challenge at CES.[77]

Classification

Qualifying

| Pos | No. | Driver | Team | Speed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 82 | KV Racing Technology – Lotus | 222.078 | ||||||

| 2 | 2 | Newman/Haas Racing | 222.061 | ||||||

| 3 | 67 | Sarah Fisher Racing | 221.509 | ||||||

| 4 | 98 | Bryan Herta Autosport | 221.330 | ||||||

| 5 | 6 | Team Penske | 221.130 | ||||||

| 6 | 26 | Andretti Autosport | 221.129 | ||||||

| 7 | 28 | Andretti Autosport | 221.040 | ||||||

| 8 | 38 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 220.958 | ||||||

| 9 | 7 | Andretti Autosport | 220.925 | ||||||

| 10 | 27 | Andretti Autosport | 220.922 | ||||||

| 11 | 3 | Team Penske | 220.907 | ||||||

| 12 | 17 | AFS Racing/Sam Schmidt Motorsports | 220.790 | ||||||

| 13 | 9 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 220.715 | ||||||

| 14 | 06 | Newman/Haas Racing | 220.701 | ||||||

| 15 | 4 | Panther Racing | 220.639 | ||||||

| 16 | 5 | KV Racing Technology – Lotus | 220.627 | ||||||

| 17 | 12 | Team Penske | 220.524 | ||||||

| 18 | 10 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 220.489 | ||||||

| 19 | 44 | Panther Racing | 220.3921 | ||||||

| 20 | 34 | Conquest Racing | 220.335 | ||||||

| 21 | 19 | Dale Coyne Racing | 220.314 | ||||||

| 22 | 83 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 219.982 | ||||||

| 23 | 22 | Dreyer & Reinbold Racing | 219.942 | ||||||

| 24 | 57 | Sarah Fisher Racing | 219.816 | ||||||

| 25 | 11 | Dreyer & Reinbold Racing | 219.493 | ||||||

| 26 | 14 | A. J. Foyt Enterprises | 219.273 | ||||||

| 27 | 8 | Dragon Racing | 218.661 | ||||||

| 28 | 15 | Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing | 218.577 | ||||||

| 29 | 77 | Sam Schmidt Motorsports | 218.4102 | ||||||

| 30 | 30 | Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing | 218.157 | ||||||

| 31 | 24 | Dreyer & Reinbold Racing | 218.153 | ||||||

| 32 | 78 | HVM Racing | 218.132 | ||||||

| 33 | 59 | KV Racing Technology – Lotus | no time set | ||||||

| 34 | 18 | Dale Coyne Racing | no time set | ||||||

Notes:

Scoring when abandoned

| Pos | No. | Driver | Team | Laps | Time/Retired | Grid | Laps Led | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 82 | KV Racing Technology – Lotus | 12 | Running | 1 | 12 | |||

| 2 | 67 | Sarah Fisher Racing | 12 | Running | 3 | 0 | |||

| 3 | 6 | Team Penske | 12 | Running | 5 | 0 | |||

| 4 | 26 | Andretti Autosport | 12 | Running | 6 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 2 | Newman/Haas Racing | 12 | Running | 2 | 0 | |||

| 6 | 98 | Bryan Herta Autosport | 12 | Running | 4 | 0 | |||

| 7 | 38 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 12 | Running | 8 | 0 | |||

| 8 | 28 | Andretti Autosport | 12 | Running | 7 | 0 | |||

| 9 | 3 | Team Penske | 12 | Running | 11 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 06 | Newman/Haas Racing | 12 | Running | 14 | 0 | |||

| 11 | 5 | KV Racing Technology – Lotus | 12 | Running | 16 | 0 | |||

| 12 | 7 | Andretti Autosport | 12 | Running | 9 | 0 | |||

| 13 | 9 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 12 | Running | 13 | 0 | |||

| 14 | 10 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 12 | Running | 18 | 0 | |||

| 15 | 34 | Conquest Racing | 12 | Running | 19 | 0 | |||

| 16 | 27 | Andretti Autosport | 12 | Running | 10 | 0 | |||

| 17 | 78 | HVM Racing | 12 | Running | 30 | 0 | |||

| 18 | 24 | Dreyer & Reinbold Racing | 12 | Running | 29 | 0 | |||

| 19 | 11 | Dreyer & Reinbold Racing | 12 | Running | 24 | 0 | |||

| 20 | 18 | Dale Coyne Racing | 11 | Running | 32 | 0 | |||

| 21 | 14 | A. J. Foyt Enterprises | 11 | Contact | 25 | 0 | |||

| 22 | 17 | AFS Racing/Sam Schmidt Motorsports | 10 | Contact | 12 | 0 | |||

| 23 | 4 | Panther Racing | 10 | Contact | 15 | 0 | |||

| 24 | 22 | Dreyer & Reinbold Racing | 10 | Contact | 22 | 0 | |||

| 25 | 15 | Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing | 10 | Contact | 27 | 0 | |||

| 26 | 57 | Sarah Fisher Racing | 10 | Contact | 23 | 0 | |||

| 27 | 83 | Chip Ganassi Racing | 10 | Contact | 21 | 0 | |||

| 28 | 8 | Dragon Racing | 10 | Contact | 26 | 0 | |||

| 29 | 59 | KV Racing Technology – Lotus | 10 | Contact | 31 | 0 | |||

| 30 | 77 | Sam Schmidt Motorsports | 10 | Contact (fatal) | 34 | 0 | |||

| 31 | 19 | Dale Coyne Racing | 10 | Contact | 20 | 0 | |||

| 32 | 30 | Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing | 10 | Contact | 28 | 0 | |||

| 33 | 12 | Team Penske | 10 | Contact | 17 | 0 | |||

| 34 | 44 | Panther Racing | 10 | Contact | 33 | 0 | |||

Source:[16] | |||||||||

Standings after the race

| Pos | Driver | Points | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 573 | |||||||

| 2 | 555 | |||||||

| 3 | 518 | |||||||

| 4 | 425 | |||||||

| 5 | 366 | |||||||

Source:[80] | ||||||||

- Note: Only the Top 5 positions are included.

See also

References

- "2011 IZOD IndyCar World Championship weather information". The Old Farmers' Almanac. Yankee Publishing. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- "Dan Wheldon's fatal crash at LVMS recalled 10 years later". October 16, 2021.

- Garrett, Jerry (October 18, 2011). "Worries Circled Las Vegas Track Before a Pileup". The New York Times.

- "INDYCAR to cap 2011 season at Las Vegas Motor Speedway". Las Vegas Motor Speedway (Press release). Speedway Motorsports, Inc. February 22, 2011. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- Fryer, Jenna (October 18, 2011). "Factors converged in crash that killed Dan Wheldon". Yahoo! News. Yahoo Inc. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Hall, Andy (October 10, 2011). "Motorsports This Week on ESPN and ABC". ESPN PressRoom. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- "Outsiders eligible for IndyCar title race". ESPN. February 22, 2011.

- Allen, James (October 16, 2011). "Dan Wheldon". James Allen on F1. James Allen. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Caldwell, Dave (February 24, 2011). "IndyCar's $5 Million Las Vegas Challenge Is a Ringer's Delight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- Sturbin, John (September 14, 2011). "Bernard Revises INDYCAR Vegas Challenge". Racintoday.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- Peltz, Jim (October 3, 2011). "IndyCar racing fires on all cylinders at Kentucky event". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011.

- "Hawk to be Grand Marshal at Vegas". PaddockTalk. October 12, 2011. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- Levin, Andrew (October 15, 2011). "Las Vegas – Qualifying times". Crash. Crash Media Group. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- "Tony Kanaan takes pole for season finale in Las Vegas". AutoWeek. Crain Communications. October 14, 2011. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Bradley, Charles (October 16, 2011). "IndyCar finale red-flagged after 13-car accident". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- "2011 IZOD IndyCar World Championships". Racing-Reference. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Oreovicz, John (October 17, 2011). "Dan Wheldon's death stuns racing world". ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Cheever, Eddie (October 16, 2011). IZOD IndyCar World Championship (Television production). Las Vegas, Nevada, United States: American Broadcasting Company.

- Clark, Laine (October 17, 2011). "IndyCar drivers want change after fatality". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Australian Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- "Dan Wheldon dies in huge crash at IndyCar finale". USA Today. David Hunke; Gannett Company. Associated Press. October 16, 2011. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Ritter, Ken (October 17, 2011). "Wheldon died of head injuries". Yahoo! Sports. Yahoo!. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- "Dan Wheldon dies following IndyCar crash at Vegas". ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Lewandowski, Dave (October 16, 2011). "Wheldon succumbs to injuries in crash". IndyCar Series. IndyCar. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- "Briton Dan Wheldon dies in IndyCar race in Las Vegas". BBC Sport. BBC. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Cavin, Curt (October 17, 2011). "Dan Wheldon had been helping IndyCar with safety for 2012". USA Today. David Hunke; Gannett Company. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- "Dan Wheldon's death ignites fresh IndyCar danger debate". PerthNow. News Limited. Agence France-Presse. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- "Motorsport pays tribute to Dan Wheldon". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. October 16, 2011. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- "Courtney: Wheldon's fate a reality check". Speedcafe.com. SpeedCafe. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- "V8s and teams plan tributes to Wheldon". Speedcafe.com. SpeedCafe. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- "Wheldon's name to run on #1 HRT window". Speedcafe.com. SpeedCafe. October 20, 2011. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- "BRDC members pay tribute to Dan Wheldon". Speedcafe.com. SpeedCafe. October 20, 2011. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Noble, Jonathan (October 17, 2011). "Tony Kanaan and Will Power pull out of all-star Surfers race". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- O'Leary, Jamie; Strang, Simon (October 18, 2011). "Sam Schmidt could close team following Dan Wheldon's death". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Noble, Jonathan (October 18, 2011). "Paul Tracy hopes that Dan Wheldon's death acts as spur for IndyCar chiefs to improve oval safety". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Newton, David (October 20, 2011). "Wheldon tribute in works at Talladega". ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- "IndyCar: NASCAR drivers to display Dan Wheldon tribute decals at Talladega". Autoweek. October 20, 2011. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- The Racer's Group (October 21, 2011). "TRG Motorsports to field two cars at Talladega II". Motorsport. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- Cavin, Curt (January 6, 2012). "IndyCar season may conclude in Fort Lauderdale". The Indianapolis Star. Karen Crotchfelt; Gannett Company. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- "IndyCar will not race at Las Vegas in 2012 after Dan Wheldon's fatal crash". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. December 9, 2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "IndyCar won't race Las Vegas in '12". ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures. Associated Press. December 8, 2011. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "IndyCar: Single-file restarts to return; standing starts next?". Autoweek. Crain Communications. February 13, 2012. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- Francis, Enjoli (October 17, 2011). "Crowded Track, Young Drivers Factor in Fatal Indy Crash, Expert Says". ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- "Will Power says Las Vegas race was a "recipe for disaster"". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. October 19, 2011. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- Martin, Bruce (October 17, 2011). "Changes to IndyCar need to be made following Wheldon's death". CNN Sports Illustrated. Time Inc. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Strang, Simon (October 18, 2011). "Las Vegas boss defends venue in aftermath of Wheldon accident". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- "Jody Scheckter wants son to quit IndyCar after Dan Wheldon's death". BBC Sport. BBC. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Mejia, Diego (October 17, 2011). "Jimmie Johnson thinks IndyCar should quit racing on ovals". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Miller, Robin (October 19, 2011). "Jimmie Johnson clarifies his oval racing statements". SPEEDTV.com. Speed. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Bradley, Charles (October 18, 2011). "Mario Andretti says Dan Wheldon's fatal Indycar crash was "freakish" one-off". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Noble, Jonathan (October 20, 2011). "Mosley says IndyCar should take calm approach to Wheldon investigation". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Richards, Giles (October 18, 2011). "Dan Wheldon's death puts cockpits back on the agenda in F1". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- "Race Car Driver Says Las Vegas Track Was Too Dangerous". Inside Edition. CBS Television Distribution. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- Martin, Bruce (March 3, 2011). "Bernard hopes $5 million challenge can renew interest in IndyCar". Sports Illustrated. Time Inc. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

The only NASCAR driver so far who expressed interest is former Champ Car Series driver A. J. Allmendinger.

- "Drivers saw dangers in IndyCar finale". Fox Sports. October 16, 2011. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- "Kimi Räikköstä houkuteltiin kohtalokkaaseen kisaan" [Kimi Räikkönen lured into a fateful contest]. Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish). Sanoma. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Glendenning, Mark (December 15, 2011). "Indycar confirms contact with fence pole caused Dan Wheldon's death at Las Vegas". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- Strang, Simon (October 19, 2011). "FIA to assist IndyCar Series in its investigation into Dan Wheldon's death". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- Glendenning, Mark (December 15, 2011). "IndyCar's Barnhart says Las Vegas banking not to blame for Wheldon's accident". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- "2011 Las Vegas Accident Investigation" (PDF). CNN Sports Illustrated. Brickyard.com; IMS LLC. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- Morales, Robert (April 6, 2017). "James Hinchcliffe recalls near-fatal crash at Indy 500". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- DiZinno, Tony (June 28, 2015). "DiZinno: IndyCar's Double-Edged Sword in Fontana". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- DeZinno, Tony (June 11, 2017). "IndyCar field brings 'pack race' term back to vernacular at Texas". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- Noble, Jonathan (July 27, 2017). "Refusing Halo would be "ignorant and stupid" – Vettel". Motorsport.com. Motorsport Network. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- Tucker, Heather (February 16, 2016). "AJ Allmendinger: I'll never race open cockpit again". USA Today. Gannett Company. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- FIA (July 19, 2017). "Halo protection system to be introduced for 2018". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- Kalinauckas, Alex (August 31, 2017). "Formula 2 unveils 2018 car with Halo". Motorsport.com. Motorsport Network. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- Errington, Tom (October 19, 2017). "United States F3 series launched, 2018 car revealed with halo". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- Edmondson, Laurence (January 30, 2018). "Formula E reveals next generation car with Halo". ESPN.com. ESPN Internet Ventures. Archived from the original on April 16, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- The Aeroscreen Official Site of Indycar. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- "Video:Dario Franchitti involved in horrific crash at IndyCar race in Houston". Autoweek. Crain Communications. October 5, 2013. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- "Frame by frame: Scott Dixon's insane crash at the Indy 500". Motorsport.com. Motorsport Network. May 30, 2017. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Robinson, Mark (August 2, 2017). "Test Drivers Like Exposed Rear Tires on Universal Aero Kit". IndyCar.com. Brickyard Trademarks, Inc. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Malshar, David (September 20, 2017). ""Awesome" 2018 IndyCar aerokit will improve racing, says Servia". Motorsport.com. Motorsport Network. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Kantowski, Ron (October 16, 2021). "Dan Wheldon's fatal crash at LVMS recalled 10 years later". Las Vegas Review-Journal. LaVRJ. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- @NYeoman (October 16, 2022). "Here's to remembering legends and creating better memories on October 16th" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Polimove Wins the Autonomous Challenge at CES®, Making History as the First Head-To-Head Autonomous Racecar Competition Champion". Indy Autonomous Challenge. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- "PoliMOVE Wins the Autonomous Challenge @ CES 2023, Setting a New Autonomous Speed World Record for a Racetrack". Indy Autonomous Challenge. IMS. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- "2011 IZOD IndyCar World Championships qualifying results". Racing-Reference. Fox Sports Digital. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- Strang, Simon (October 15, 2011). "Buddy Rice sent to back of Vegas grid after penalty". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- "IZOD IndyCar Series standings for 2011". Racing-Reference. Fox Sports Digital. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2015.