Columbus Day Storm of 1962

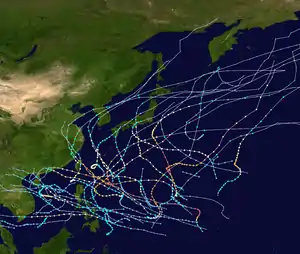

The Columbus Day Storm of 1962 (also known as the Big Blow,[2] and originally, and in Canada as Typhoon Freda) was a Pacific Northwest windstorm that struck the West Coast of Canada and the Pacific Northwest coast of the United States on October 12, 1962. Typhoon Freda was the twenty-eighth tropical depression, the twenty-third tropical storm, and the eighteenth typhoon of the 1962 Pacific typhoon season. Freda originated from a tropical disturbance over the Northwest Pacific on September 28. On October 3, the system strengthened into a tropical storm and was given the name Freda, before becoming a typhoon later that day, while moving northeastward. The storm quickly intensified, reaching its peak as a Category 3-equivalent typhoon on October 5, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 948 millibars (28.0 inHg). Freda maintained its intensity for another day, before beginning to gradually weaken, later on October 6. On October 9, Freda weakened into a tropical storm, before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone on the next day. On October 11, Freda turned eastward and accelerated across the North Pacific, before striking the Pacific Northwest on the next day. On October 13, the cyclone made landfall on Washington and Vancouver Island, and then curved northwestward. Afterward, the system moved into Canada and weakened, before being absorbed by another developing storm to the south on October 17. The Columbus Day Storm of 1962 is considered to be the benchmark of extratropical wind storms. The storm ranks among the most intense to strike the region since at least 1948, likely since the January 9, 1880 "Great Gale" and snowstorm. The storm is a contender for the title of the most powerful extratropical cyclone recorded in the U.S. in the 20th century; with respect to wind velocity, it is unmatched by the March 1993 "Storm of the Century" and the "1991 Halloween Nor'easter" ("The Perfect Storm"). The system brought strong winds to the Pacific Northwest and southwest Canada, and was linked to 46 fatalities in the northwest and Northern California resulting from heavy rains and mudslides.

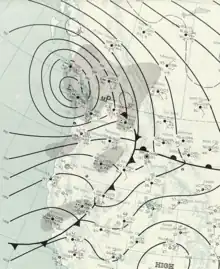

Surface Analysis of the storm near its peak intensity[1] | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 28, 1962 |

| Extratropical | October 10, 1962 |

| Dissipated | October 17, 1962 |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 185 km/h (115 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 948 hPa (mbar); 27.99 inHg |

| Extratropical cyclone | |

| Highest gusts | 170 mph (270 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 960 hPa (mbar); 28.35 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 46 |

| Damage | $230 million (1962 USD) |

| Areas affected | Northern California, Pacific Northwest, Canada |

Part of the 1962 Pacific typhoon season and 1962–63 North American winter | |

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On the morning of September 28, a tropical disturbance formed south of the island of Eniwetok Atoll. After moving westward and making a large bend around the island, the new system slowly gained strength, and on the morning of October 3, the system became a tropical storm about 500 miles (800 km) from Wake Island, over the central Pacific Ocean.[3] Now named Freda, the system rapidly intensified as it proceeded northeastward over the open Pacific waters. On that afternoon, Freda intensified into a typhoon, with 1-minute sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). On October 4, the typhoon quickly intensified, reaching its peak of 115 mph (185 km/h) on the next day, with a minimum central pressure of 948 millibars (27.99 inHg), making the storm the equivalent of a Category 3 typhoon on the Saffir–Simpson scale. After stabilizing to the north, Freda maintained its strength through the Pacific, before beginning to weaken slowly on October 6. Making a turn to the northeast, Freda maintained typhoon-status winds for several more days, before weakening into a tropical storm on October 9, as it started experiencing the effects of cold air.[4]

Moving northeastward at a steady rate of 16 mph (26 km/h), the storm slowly underwent an extratropical transition, becoming extratropical operationally on the morning of October 10, still with winds of 45 mph (65 km/h).[4] The system became an extratropical cyclone as it moved into colder waters and interacted with the jet stream. However, post-season analysis concluded that the system continued weakening as it continued northeastward, crossing the 180th meridian later that afternoon, before completing the transition that evening.[5]

The extratropical low redeveloped intensely off the coast of Northern California, due to favorable upper-level conditions, producing record rainfall across the San Francisco Bay Area that delayed some games in the 1962 World Series between the San Francisco Giants and the New York Yankees. The low moved northeastward, and then hooked straight north, as it neared southwest Oregon. The storm then raced nearly northward at an average speed of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h), with the center situated just 50 miles (80 km) off the Pacific Coast. There was little central pressure change until the cyclone passed the latitude of Astoria, Oregon, at which time the low began to degrade. On October 13, the center passed over Tatoosh Island, Washington, before making landfall on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, where it weakened rapidly. The cyclone then curved northwestward, before turning back eastward and moving into Canada. As the cyclone moved through Canada, another cyclone formed on its southern periphery, which absorbed the original cyclone by October 17.[6]

The extratropical cyclone deepened to a minimum central pressure of at least 960 hPa (28 inHg), and perhaps as low as 958 hPa (28.3 inHg), a pressure which would be equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale (SSHS). Since the system was an extratropical cyclone, its wind field was neither as compact nor as strong as a tropical cyclone, though its wind field was significantly larger. All-time record-low land-based pressures (up to 1962) included 969.2 hPa (28.62 inHg) at Astoria, 970.5 hPa (28.66 inHg) at Hoquiam, Washington, and 971.9 hPa (28.70 inHg) at North Bend, Oregon. The Astoria and Hoquiam records were broken by a major storm on December 12, 1995 (which measured 966.1 hPa (28.53 inHg) at Astoria); however, this event did not generate winds as intense as the Columbus Day Storm of 1962.

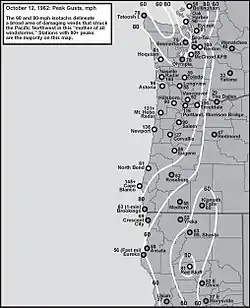

Wind speed highlights

The peak winds were felt as the storm passed close by on October 12. At Oregon's Cape Blanco, an anemometer that lost one of its cups registered wind gusts in excess of 145 miles per hour (233 kilometers per hour); some reports put the peak velocity at 179 mph (288 km/h). The north Oregon coast Mt. Hebo radar station reported winds of 170 mph (270 km/h).[8]

At the Naselle Radar Station in the Willapa Hills of southwest Washington, a wind gust of 160 mph (260 km/h) was observed.[7]

In Salem, Oregon, a wind gust of 90 mph (140 km/h) was observed.[7]

At Corvallis, Oregon, an inland location in the Willamette Valley, one-minute average winds reached 69 miles per hour (111 km/h), with a gust to 127 mph (204 km/h), before the station was abandoned due to "power failure and instruments demolished". Observations at the weather station resumed the next day.[7]

About 80 miles (130 km) to the north, at Portland, Oregon's major metropolitan area, measured wind gusts reached 116 mph (187 km/h) at the Morrison Street Bridge in downtown Portland.

A peak gust of 92 mph (148 km/h) was observed in Vancouver, Washington at Pearson Field, around 9 miles (14 km) to the north of downtown Portland.

Many anemometers, official and unofficial, within the heavily stricken area of northwestern Oregon and southwest Washington were damaged or destroyed before winds attained maximum velocity. For example, the wind gauge atop the downtown Portland studios of KGW radio and TV recorded two gusts of 93 mph (150 km/h), just before flying debris knocked the gauge off-line[9] shortly after 5 p.m.

For the Willamette Valley, the lowest peak gust officially measured was 86 mph (138 km/h) at Eugene. This value, however, is higher than the maximum peak gust generated by any other Willamette Valley windstorm in the 1948–2010 period.

In the interior of western Washington, officially measured wind gusts included 78 miles per hour (126 km/h) at Olympia, 88 mph (142 km/h) at McChord Air Force Base, 100 mph (160 km/h) at Renton at 64 feet (20 m) and 98 mph (158 km/h) at Bellingham. In the city of Seattle, a peak wind speed of 65 mph (105 km/h) was recorded; this suggests gusts of at least 80 mph (130 km/h). Damaging winds reached as far inland as Spokane.

Wind gusts of 58 mph (93 km/h), the National Weather Service minimum for "High Wind Criteria," or higher were reported from San Francisco, to Vancouver, British Columbia.

Impact

At least 46 fatalities were attributed to this storm, more than for any other Pacific Northwest weather event.[10] Injuries went into the hundreds. In terms of natural disaster-related fatalities for the 20th century, only Oregon's Heppner Flood of 1903 (247 deaths), Washington's Wellington avalanche of 1910 (96 deaths), the Great Fire of 1910 (87 deaths), and Eruption of Mount St. Helens of 1980 (57 deaths) caused more. For Pacific Northwest windstorms in the 20th century, the runner up was the infamous October 21, 1934, gale, which caused 22 fatalities, mostly in Washington.

In less than 12 hours, more than 11 billion board feet (26,000,000 m3) of timber was blown down in northern California, Oregon and Washington combined; some estimates put it at 15 billion board feet (35,000,000 m3). This exceeded the annual timber harvest for Oregon and Washington at the time. This value is above any blowdown measured for East Coast storms, including hurricanes; even the often-cited 1938 New England hurricane, which toppled 2.65 billion board feet (6,300,000 m3), falls short by nearly an order of magnitude.

Estimates put the dollar damage at approximately $230 million to $280 million for California, Oregon, and Washington combined. Those figures in 1962 US dollars translate to $1.8 to $2.2 billion in 2014 US dollars. Oregon's share exceeded $200 million in 1962 US dollars. This is comparable to land-falling hurricanes that occurred within the same time frame (for example, Audrey, Donna, and Carla from 1957 to 1961).[11]

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. (now MetLife) named the Columbus Day Storm the nation's worst natural disaster of 1962.[12]

California

In Central and Northern California, all-time record rains associated with the atmospheric river along the cold front caused major flooding and mudslides, particularly in the San Francisco Bay Area. Oakland set an all time calendar day record with 4.52 inches (115 mm) of rain on the 13th, as did Sacramento with 3.77 inches (96 mm). More than 7 inches (180 mm) of rainfall were recorded in the Bay area.[13]

Heavy rain forced Game 6 of the 1962 World Series at San Francisco's Candlestick Park to be postponed from its originally scheduled date of October 11 to Monday, October 15.

Oregon

In the Willamette Valley, it is said the undamaged home was the exception. Livestock suffered greatly due to the barn failures: the animals were crushed under the weight of the collapsed structures, a story that was repeated many times throughout the afflicted region. At the north end of the Valley, two 500-foot (150 m) high voltage transmission towers were toppled.

Radio and TV broadcasting were affected in the Portland area. KGW-TV lost its tower at Skyline and replaced the temporary tower with a new one on January 28, 1963. KOIN radio lost one of two AM towers at Sylvan. KPOJ-AM/-FM lost much of its transmitting equipment, plus one of two towers was left partially standing at Mount Scott. KPOJ-FM was so badly damaged it wouldn't return to the air until February 9, 1963. KWJJ-AM lost one of its towers and a portion of its transmitter building at Smith Lake. KISN-AM also lost a tower at Smith Lake. Seven-month-old TV station KATU did not receive any damage at its Livingston Mountain site, 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Camas, Washington. However, KATU didn't have a generator and power was cut off. The heavy-duty design of the radio towers on Portland's West Hills today, with extensive and robust guy cables, is a direct result of the lessons learned from the 1962 catastrophe.

For northwest Oregon, the entire power distribution system had to be rebuilt from the ground up. Some locations did not have power restored for several weeks.[10] This storm became a lasting memory for local power distributors. Indeed, a number of high wind related studies appeared in the years after the storm in an attempt to assess the return frequency of such potentially damaging winds.

The state capitol grounds at Salem, and the state's college campuses, resembled battlefields with heavy losses of trees.

The Campbell Hall tower at Oregon College of Education (now Western Oregon University) in Monmouth crashed to the ground,[14] an event recorded by student photographer Wes Luchau in the most prominent picture-symbol of the storm.

East of Salem, the wind destroyed a historic barn that served as a clandestine meeting place by pro-slavery Democratic members of the state Legislature in 1860.

The Oregon State Beavers–Washington Huskies college football game went on as scheduled Saturday, October 13 in Portland, in a heavily damaged Multnomah Stadium. Much of the roof was damaged and seats damaged by falling debris were replaced by portable chairs.[15] Crews cleared debris from the grandstand and playing field right up to kickoff.[15] Most of the electricity, including the scoreboard and clock, was still out and players dressed by candlelight in the locker rooms.[16] The Huskies came from behind to beat the Beavers 14–13, despite a strong performance by quarterback Terry Baker, who would win the Heisman Trophy later that year.[16][17]

British Columbia

The storm weakened as it traveled north into British Columbia, with peak gusts measured at 90 miles per hour (140 km/h).[18] Five people in British Columbia were killed in the storm,[19] and the area suffered $80 million in damages.[20] Stanley Park lost 3,000 trees. A Victoria resident described it as "Just general devastation everywhere you went. There were trees breaking off and flying across the roads. "Wind was just blowing the rain horizontal and trees were weaving all over the place. You didn't know if you were going to get hit or not."[21] At Victoria airport, a Martin Mars waterbomber ("Caroline Mars") was hurled 200 yards (180 m) and irreparably damaged.[22]

See also

References

- "Daily Weather Maps: October 13, 1962". U.S. Weather Bureau. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- Burt, Christopher C. (2004), Extreme Weather: A Guide and Record Book, W.W. Norton & Co., p. 236, ISBN 978-0-393-32658-1

- Al Sholand. "Typhoon Freda stormed in to town". Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Annual Tropical Cyclone Report – 1962" (PDF). Pearl Harbor, Hawaii: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 1962. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- "Best Track - Typhoon Freda". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- "Daily Weather Maps: October 17, 1962". U.S. Weather Bureau. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- Read, Wolf (October 27, 2015). "The 1962 Columbus Day Storm". The Storm King. Office of the Washington State Climatologist (OWSC). Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- "Spokane Daily Chronicle - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- "Columbus Day Storm still howls through Portland history, 50 years later". OregonLive.com. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- "The Mightiest Wind: The 1962 Columbus Day Storm". September 7, 2012. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "CPI Inflation Calculator". US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- "Terrible Tempest of the 12th". Climate.washington.edu. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- J. L. Baldwin Weekly Weather and Crop Bulletin. U.S. Department of Commerce, p. 1.

- Burt, Christopher C. (2004), Extreme Weather: A Guide and Record Book, W.W. Norton & Co., p. 237, ISBN 978-0-393-32658-1

- "Friday night's violent winds wreck Multnomah Stadium". The Register-Guard. October 14, 1962. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- Smith, Craig (October 12, 2004). "Punting into this storm sent averages plummeting". The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- Harvey III, Paul (October 14, 1962). "Huskies nip Beavers". The Register-Guard. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- "The Columbus Day "Big Blow" Of 1962 Set The Bar For Pacific Northwest Storms | Weather Concierge". October 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "Columbus Day windstorm ravages Puget Sound region on October 12, 1962". www.historylink.org. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "The Columbus Day Storm of 1962". Farmers’ Almanac. October 7, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "Typhoon Freda slams B.C. coast in 1962". CBC.ca. October 15, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Bill Gabbert (December 5, 2011). "Looking back at the Martin Mars".

On October 12, 1962, while parked ... at the Victoria International Airport on Vancouver Island, it was damaged beyond repair by Typhoon Freda when she was blown 200 yards across the airport.

Further reading

- John Dodge (2018). A Deadly Wind: The 1962 Columbus Day Storm. Oregon State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87071-928-8.

External links

- Windstorms Brochure (PDF) from the National Weather Service Forecast Office in Portland, Oregon

- Lynott, Robert E.; Cramer, Owen P. (February 1966). "Detailed Analysis Of The 1962 Columbus Day Windstorm In Oregon And Washington" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 94 (2): 105–117. Bibcode:1966MWRv...94..105L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.1937. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1966)094<0105:daotcd>2.3.co;2. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- Heidorn, Keith C. (October 1, 2007). "Typhoon Freda: The Columbus Day Storm". The Weather Doctor. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- "Columbus Day, 1962 – Photo gallery". National Weather Service Portland. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- Clements, Kathleen Carlson. "Columbus Day Storm: "Worst Disaster Ever"". Salem Online History. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- Sistek, Scott (October 12, 2012). "50 Years Later, Columbus Day Windstorm Still Ranks As Greatest". Komonews.com. Retrieved October 28, 2012.