18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment

The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment (also known as the 163rd Pennsylvania Volunteers) was a cavalry regiment of the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was present for 50 battles, beginning with the Battle of Hanover in Pennsylvania on June 30, 1863, and ending with a skirmish at Rude's Hill in Virginia during March 1865. A majority of its fighting was in Virginia, although its first major battle was in Pennsylvania's Gettysburg campaign. It was consolidated with the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment on June 24, 1865, to form the 3rd Provisional Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment.

| 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment | |

|---|---|

Flag of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment | |

| Active | Fall 1862 to June 24, 1865 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Union Army |

| Type | Cavalry |

| Engagements | American Civil War 1863: Battle of Hanover, Battle of Gettysburg, Battle of Williamsport, Battle of Mine Run 1864: Battle of the Wilderness, Battle of Todd's Tavern, Battle of Yellow Tavern, Battle of Cold Harbor, Battle of Saint Mary's Church, Third Battle of Winchester, Battle of Tom's Brook, Battle of Cedar Creek |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel | Timothy M. Bryan 1863–1864 |

| Lt. Colonel | William P. Brinton 1864–1865 |

| Colonel | Theo. F. Rodenbough 1865 |

The regiment was organized at Pittsburgh and Harrisburg between October and December 1862. Green County was the source of recruits for three companies, while additional recruits came from elsewhere in the state. Companies L and M were late additions to the regiment, and were originally meant to be part of a 19th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment. Recruits for these two companies were mostly from the Philadelphia area.

The regiment served in the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the Shenandoah. Among major battles where it saw action were the Battle of the Wilderness, the Third Battle of Winchester, and the Battle of Cedar Creek. It had five officers and 55 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded. Disease killed two more officers and 232 enlisted men. Captured members of the regiment were kept in Libby Prison in Richmond and Andersonville Prison in Georgia, among others. The regiment was commanded by two colonels: Timothy M. Bryan and Theophilus F. Rodenbough; Lieutenant Colonel William P. Brinton and Major John W. Phillips also commanded the regiment in the field.

Formation and organization

Between December 20, 1860, and February 1, 1861, seven southern states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America. Fighting began on April 12, 1861, when local militia attacked United States troops at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. This is considered the beginning of the American Civil War. Four additional states seceded during the next three months.[1] Ending the rebellion took longer than government leaders expected, and President Abraham Lincoln called for more troops on July 2, 1862.[2] In response to Lincoln's call for volunteer troops, Companies A through K (there was no J) were mustered into the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment from August through November.[2] The regiment was also known as "One Hundred and Sixty-third Pennsylvania Volunteers".[3][Note 1] Four of the companies were first organized in Pittsburgh, while six of the companies were organized at Camp Simmons near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.[5] Companies A, C, and G were recruited from Greene County, and Companies B and D were recruited from Crawford County.[2] Major sources for additional recruits were Allegheny, Cambria, Dauphin, Lycoming, and Washington counties.[Note 2] Captain James E. Gowen of Company E was promoted to lieutenant colonel on November 25, 1862, and was the regiment's highest-ranking officer over the next few months.[5] The other original leaders were Majors Joseph Gilmore, William B. Darlington, and Henry B. Van Voorhis.[6]

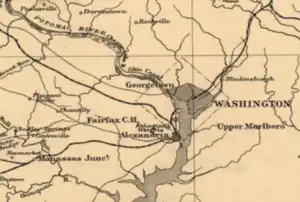

In early December 1862 the regiment moved by rail to the Bladensburg, Maryland area, close to Washington, D.C.[6] They received training at this location, and were armed with a saber and Merrill carbine. Cavalry soldiers considered this carbine inferior and "comparatively worthless".[6] Timothy M. Bryan Jr. was appointed colonel and commander of the regiment effective December 24, but did not assume command until May 1863. A West Point graduate, he had been an officer in the regular U.S. Army, and had previously been a lieutenant colonel with the 12th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.[6][7] Without Bryan, the regiment had its first mounted drill on December 25. Beginning January 1863, the regiment was attached to Colonel Percy Wyndham's Cavalry Brigade for the defense of Washington.[8] The 5th New York Cavalry and 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiments were also part of Wyndam's brigade.[9] Camp for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry was moved to Virginia on January 1, 1863, and settled a week later on the Little River Turnpike about 2 miles (3.2 km) from Fairfax Courthouse.[5][Note 3]

Early action

Historian Robert W. Black observes "the 18th Pennsylvania would become a fine regiment", but "in January 1863, it was a collection of civilians in uniform, poorly equipped and armed."[11] Their first scouting task was on January 11, when a portion of the regiment went on a late-night patrol with the 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiment, which was loyal to the Union.[5][Note 4] January and February were spent on picket duty, scouting missions, and drilling. A major foe in this area of Virginia was Major John Mosby and his partisan Rangers.[9] Soldiers of the brigade considered Mosby's force "very formidable", and pickets were always under the threat of a surprise attack.[15] On January 18, Mosby captured 11 pickets from the regiment. A few days letter, he sent a few of the captured men back to the regiment with a message that said the regiment needs to be better equipped and armed because it did not currently pay to capture them.[11]

The regiment was finally completed on February 1 when Companies L and M were added.[6] The recruits for those companies were from the Philadelphia area.[2] They were originally intended to be part of a 19th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, but that initial organization failed and they were added to the 18th.[16] When the two companies were added, the regiment became part of Colonel Richard Butler Price's Independent Cavalry Brigade, XXII Army Corps, Department of Washington.[8][17] On March 1, Gowen was discharged, and the regiment's new lieutenant colonel was William Penn Brinton, who was promoted from captain in the 2nd Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment.[18] The regiment continued to show its inexperience on March 1 when Major Joseph Gilmore led 200 men on a westward reconnaissance toward Aldie, Virginia.[Note 5] Gilmore did not follow all of his orders, and mistook some men from the 1st Vermont Cavalry for enemy soldiers.[20] He turned his command and fled at full speed from the Vermont cavalry—which caused him to be court-martialed.[21][Note 6]

In April, the regiment became part of the Third Brigade, Brigadier General Julius Stahel's Cavalry Division, XXII Army Corps.[8] Improvements were made to the regiment over the next 3 months. On April 1, revolvers, new sabers, and belts were issued.[23] Bryan joined the regiment on May 3—bringing experience and training from West Point and the regular army.[24] Burnside carbines were issued on June 21—an inferior weapon but an improvement over the Merrill carbines originally issued.[25]

Gettysburg Campaign

The Army of the Potomac, including its two cavalry divisions, moved northward from Fredericksburg, Virginia, toward Frederick, Maryland, crossing the Potomac River on June 25 and 26, 1863.[26] Stahal's cavalry division (including the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry) was detached from defending Washington so that it could join the Army of the Potomac and help defend Pennsylvania from an invasion by General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. The regiment began moving north on June 25.[25]

The entire Union army force was reorganized on June 28 at Frederick, and the regiment became part of the 3rd Division of the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac. Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick was the division's commander. The division's First Brigade consisted of the 1st Vermont, 1st West Virginia (formerly the loyal 1st Virginia), 5th New York, and 18th Pennsylvania cavalry regiments. The first three regiments were veteran units, but the 18th Pennsylvania had not yet seen a major fight.[27] Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth commanded the First Brigade, and Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer commanded the Second Brigade—which consisted of regiments from Michigan.[28] Major General Joseph Hooker was relieved of command, at his request, of the Army of the Potomac, and he was replaced by Major General George Meade.[26] The cavalry corps commander was Major General Alfred Pleasonton.[29] Brinton commanded the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment.[27]

Battle of Hanover

Kilpatrick's division was detached eastward as the army moved from Frederick, Maryland, to Pennsylvania.[30] Its mission was to prevent Confederate cavalry under the command of Major General James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart from joining the rest of Lee's army.[31] On June 30 the division proceeded to the small town of Hanover, Pennsylvania. Kilpatrick, his staff, and his bodyguards (one company from the 1st Ohio Cavalry Regiment) led the division. They were followed by Custer's Second Brigade, the artillery, and then the First Brigade. Farnsworth rode at the front of the First Brigade with the 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiment. The 1st West Virginia and 5th New York Cavalry Regiments followed them. The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment had rear guard duty.[32] The extreme rear guard consisted of 40 men from Company L and Company M led by Lieutenant Henry C. Potter, and they were about 1 mile (1.6 km) behind the main portion of the regiment.[33][Note 7] A small group of "less than a dozen" men, led by Captain Thadeus Freeland of Company E, protected the right flank as it moved a few miles east of the road to Hanover.[35] Not far from Gitt's Mill, Freeland's men and an enemy scouting party from the 13th Virginia Cavalry Regiment spotted each other, and a long-range shot killed one of the Confederates—the first casualty of the Battle of Hanover.[36]

Freeland and his men rode toward the regiment to warn of the danger, but instead found more men from the 13th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, which quickly surrounded the Pennsylvanians and captured them without firing a shot.[37] When Potter and his men were about 1 mile (1.6 km) from Hanover, they found their path to town blocked by the same group of about 60 Confederates who demanded their surrender. Potter's men responded by firing at the enemy soldiers and charging through them toward town.[38] They were followed by the enemy force and came upon the rest of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry—dismounted and mingling with the locals. Lieutenant Samuel H. Tresonthick was the only officer in the rear.[39] Most of the division had already passed through the town, but ahead of the 18th Pennsylvania was the 5th New York Cavalry, which was also enjoying refreshments and greetings provided by the locals.[40] Soon the Confederates fired an artillery shot into town, and Union soldiers faced attacks from the 13th Virginia Cavalry, a battalion from the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry Regiment, and finally the 9th Virginia Cavalry Regiment.[41] Most of the Union fighters in the streets were from the 18th Pennsylvania and 5th New York Cavalry Regiments.[42] After close-quarter fighting, the Confederates withdrew to the cover of their artillery in the hills. The streets were full of dead and wounded men and horses. Kilpatrick directed a counterattack by portions of Farnsworth's First Brigade and Custer's Second Brigade. The counterattack silenced the Confederate big guns, and Stuart's men were driven away in this inconclusive battle. Casualties for all participants on both sides totaled to 228.[43] Casualties for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment were four killed, 30 wounded, and 52 missing.[44] Some of the men received saber wounds, including Lieutenant John Britton.[29]

Battle of Gettysburg

On July 1, Farnsworth's Brigade was in the Abbottstown-Berlin area of Pennsylvania. They chased rebel cavalry and captured several prisoners.[45] On July 2, the division moved closer to Gettysburg, and was on the right side of the entire Union army—close to New Oxford and Hunterstown.[45] On July 3, the First Brigade moved to the left wing of the army, about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from Gettysburg near two hills known as Little Round Top and Big Round Top.[45] For most of the day, the 18th Pennsylvania was at the rear of the brigade, and conducted only a few scouting tasks with small groups of soldiers.[46]

Late in the afternoon, the brigade was ordered to make mounted charges through rocky and wooded terrain.[46] The cavalry regiments were positioned with the 18th Pennsylvania on the left, the 1st West Virginia in the middle, and the 1st Vermont on the right.[Note 8] The 1st West Virginia Cavalry made the first charge.[48] They became nearly surrounded by enemy soldiers from the 1st Texas Infantry Regiment and had to retreat to safety using sabers.[49] The 18th Pennsylvania went next.[48] They charged across a field through woods interspersed with boulders where they confronted the same Texas infantry, who were protected by a stone fence. The Confederates fired too high, which kept the regiment from suffering serious losses—but the charge was repulsed.[46]

The 1st Vermont Cavalry charged next, although Farnsworth thought the charge was unwise. The First and Second Battalions of the 1st Vermont Cavalry made the mounted change, while the Third Battalion was placed behind a stone wall as a reserve if the charge was repulsed. Farnsworth rode with the Second Battalion.[50] Although this charge by the 1st Vermont Cavalry is often described as a single charge, it was really a series of charges that were able to cross the rebel skirmish line before being repulsed.[50] A total of 67 of the estimated 300 Vermont men in the charge were killed, wounded, or missing.[51] Farnsworth was killed, and at least one cavalry leader was critical of Kilpatrick's decision to order a mounted charge in terrain that was not ideal for cavalry.[52]

After the charges, the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry returned to the open field and formed a dismounted skirmish line.[46] The fighting ended that evening in a drenching rain.[53] About 166,000 soldiers fought in "the bloodiest single battle of the entire war"—with casualties in this Union victory estimated to be 23,000 for the Union force and 28,000 for the Confederates.[54] Casualties for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry were one killed, five wounded, and eight missing.[44]

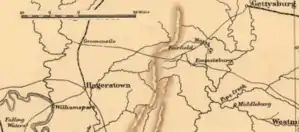

Battle of Williamsport

After the Battle of Gettysburg, Lee's army retreated toward Williamsport, Maryland, where it planned to cross the Potomac River to the relative safety of Virginia. In this retreat, Lee sent a wagon train of wounded men on a longer and more northerly route to Virginia.[55] The healthy part of Lee's army used a southwestern route to Williamsport that went through mountainous terrain.[56] Kilpatrick's division, after receiving reinforcements at Emmitsburg, Maryland, was part of the Union pursuit. As Meade's army pursued Lee, several battles and skirmishes occurred—including a fight by Kilpatrick's division in the mountains at Monterey Pass where a Confederate wagon train was captured.[57] Both portions of Lee's army, the wagon train of wounded men and the healthy soldiers, needed to pass through Hagerstown, Maryland, on their separate routes to Williamsport. The Battle of Williamsport, also known as Battle of Hagerstown, was part of Meade's attempt to prevent Lee's escape.[58]

Most of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry's fighting took place in Hagerstown, which is located on the National Road six miles (9.7 km) from the Potomac River. On the morning of July 6, Kilpatrick attacked rebel-occupied Hagerstown. Four companies from the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry made charges into town. Captain William C. Lindsay led Companies A and B with Captain Ulric Dahlgren, who was not part of the regiment but was an Acting Volunteer Aid to the division's commanding general. Lindsay, Sergeant Joseph Brown (Company B), and others were killed in close fighting in the streets of the town.[59] Dahlgren took command and was wounded in the leg, which eventually required an amputation. Companies L and M, led by Captain Enos J. Pennypacker, also made charges into town. Pennypacker's horse was killed and he was severely wounded, and Lieutenants William L. Laws and Henry C. Potter were among the men captured.[59] Laws later died at Libby Prison.[60] Losses for the regiment were eight killed, 19 wounded, and 71 missing.[44] Captain Charles J. Snyder of the 1st Michigan Cavalry Regiment, who was temporarily leading a group from the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, was also killed.[60] Over the next few days, the regiment skirmished at Boonesboro, Funkstown, and Hagerstown (again)—and suffered no casualties. At Falling Waters on July 14, they were not engaged.[61] Lee's army crossed the Potomac at Williamsport and Falling Waters on July 14.[62] The Army of the Potomac eventually crossed back to Virginia, and the headquarters of the 3rd Division was established near Warrenton.[63]

Bristoe and Mine Run campaigns

For the rest of the summer of 1863, the regiment spent its time in Virginia and was involved in picket duty, scouting, and a few skirmishes. The regiment's horses were gradually replenished. In August, the 2nd New York Cavalry Regiment was added to the First Brigade while the 1st Vermont Cavalry moved to Custer's Second Brigade, and Brigadier General Henry E. Davies Jr. became commander of the First Brigade.[64]

The Army of the Potomac's Bristoe campaign began October 9 and was fought against the Army of Northern Virginia.[65] Several of the battles in this campaign were near railroad stations belonging to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, including the Battle of Bristoe Station and the Second Battle of Rappahannock Station.[66] Major Van Voorhis commanded the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry at the start of the Bristoe Campaign.[67]

The most difficult fighting for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Bristoe campaign happened near Brandy Station on October 11. After the division became surrounded, the 18th Pennsylvania was among the regiments that charged through the enemy.[68] Van Voorhis was seriously wounded, ultimately losing an arm, and was captured along with three other officers and 32 enlisted men.[69][70] Casualties for the regiment were one killed, three wounded, and 53 missing for a total of 57 of the brigade's 119 casualties listed by the brigade commander.[71] Despite the casualties, Davies said the charge by the brigade was "most successful" and "repulsed the rebels".[72] He also praised Van Voorhis for "gallantly charging at the head of his regiment at Brandy Station."[73]

On November 18 most of the regiment went on a scouting mission towards the Rapidan River. While the regiment was away, their camp was attacked. Pickets, a small camp guard, and sick men were the only defenders. A regimental flag, 49 men, the assistant surgeon, horses, wagons, and all of the camp equipment were captured.[74]

The Army of the Potomac's Mine Run campaign began November 26 and continued fighting against the Army of Northern Virginia.[75] General Pleasonton continued to command the cavalry corps, but there were a few changes that affected the 18th Pennsylvania. While Davies still commanded the First Brigade, Custer now commanded the 3rd Division, and Bryan took over field command of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry.[76] On November 26, the regiment fought dismounted near Raccoon Ford on the Rapidan River. Fighting continued in early December, including artillery duels. On December 11, the regiment went to winter quarters at Stevensburg, Virginia.[77]

Grant's Overland Campaign

During March 1864, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant became commander of all Union armed forces.[78] Although Grant did not replace Meade as commander of the Army of the Potomac, he kept his headquarters with Meade's and provided direction. Major General Philip Sheridan was appointed commander of Meade's cavalry corps.[79] Kilpatrick was assigned to another command, and Major General James H. Wilson replaced him as commander of Sheridan's 3rd Division.[80] Colonel John B. McIntosh replaced Davies as commander of the cavalry division's First Brigade—which consisted of the 18th Pennsylvania, 1st Connecticut, 2nd New York, and 5th New York Cavalry Regiments.[81] In April, Majors Darlington and Van Voorhis rejoined the regiment, missing a leg and an arm respectively.[82]

Battle of the Wilderness

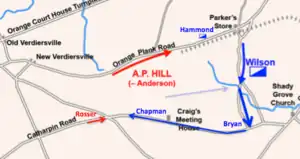

The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry fought on the first day of the Battle of the Wilderness with Brinton commanding the regiment. On May 3, the Army of the Potomac received orders to be ready to move at midnight.[83] Wilson's 3rd Division led the way, with the First Brigade on the army's right and the Second Brigade on the left. Bryan (18th Pennsylvania Cavalry) commanded the First Brigade (including the 18th Pennsylvania) while Colonel George H. Chapman commanded the Second.[84] After crossing the Rapidan River at Germanna Ford, the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry led the advance all the way to Wilderness Tavern.[85]

At 5:00 am on May 5, the brigade began moving south toward Catharpin Road, leaving the 5th New York Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Hammond and armed with repeating rifles, to guard a western approach on Orange Plank Road.[86] Hammond soon discovered that he was facing an entire infantry corps under the command of Lieutenant General A. P. Hill.[86] Hammond was gradually pushed back beyond Parker's Store, causing Wilson to be cut off from the rest of the Union army.[87]

Wilson continued south and then moved west on the Catharpin Road with Chapman's brigade leading and Bryan's brigade, without the 5th New York Cavalry, bringing up the rear. Just beyond Craig's Meeting House, Chapman encountered about 1,000 men under the command of Confederate Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser. Chapman's brigade, led by the 1st Vermont Cavalry, was able to push Rosser back about 2 miles (3.2 km) until Rosser outflanked him and caused a retreat.[88] With Hill's infantry on the Orange Plank Road on Wilson's north side and Rosser's cavalry occupying the Catharpin Road on his south side, Wilson was in danger of having his entire division captured.[89] He discovered a wagon track north of a road called Roberson's Run that led east and began a retreat with Chapman leading and Bryan in the rear.[90] The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, commanded by Brinton, again protected the rear and was ordered to hold for one half hour before attempting to rejoin Wilson.[91] After crossing the Po River, the wagon track led to Catharpin Road and Wilson was barely able to get his command on the road to the safety of Todd's Tavern.[92]

When Brinton and the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry arrived at the same intersection, they found it occupied by dismounted Confederate cavalry. Darlington and the First Battalion charged but were driven back by crossfire.[91] The Second Battalion, commanded by Major John W. Phillips, also charged and was driven back. Both Phillips and Darlington were wounded, and Darlington's wound was severe enough that he had to be left with the enemy.[Note 9] The regiment nearly became surrounded by cavalry, infantry, and an artillery battery, and escaped through a pine thicket and across a swamp. It rejoined Wilson's division that evening, surprising those who believed the entire regiment had been captured. In addition to the two wounded majors, Captain Frederick Zarracher was captured, and 39 men were killed, wounded, or captured.[94]

Sheridan's raid

For the next two weeks, the fighting shifted southeast to Spotsylvania Court House.[95] The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry left Fredericksburg at dawn on May 8. Wilson's division, including the 18th Pennsylvania, charged into Spotsylvania Courthouse, driving the enemy from town. Continuing the fight dismounted against enemy infantry, they held the town for about one hour before they were driven back and eventually replaced by infantry.[96][97] Brinton had his horse shot but escaped injury despite having a bullet pierce his clothing. Casualties were estimated by one captain to be "about ten men and horses killed and wounded".[98]

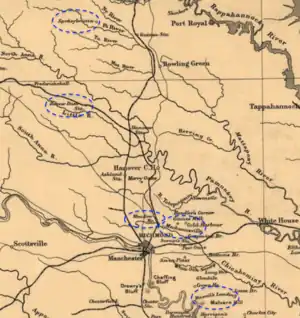

On May 9, Sheridan detached the cavalry from the Army of the Potomac and began a movement toward Richmond.[99] On the morning of the May 10, the division was awakened by enemy artillery, and pickets led by Captain Marshall S. Kingsland of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry intercepted enemy attackers.[98] Kingsland was reinforced with the entire regiment, which held off the enemy while Sheridan's entire force crossed the North Anna River. Custer's First Brigade of Merritt's 1st Division burned the Beaverdam railroad station and rescued 350 Union prisoners on their way to Richmond while the 18th Pennsylvania protected the First Brigade's right.[98] After crossing the South Anna River on May 10, Sheridan's force encountered a Confederate force led by Stuart on May 11 in a cavalry and artillery fight at Yellow Tavern on the main road to Richmond's north side.[100] Stuart was mortally wounded in fighting against Custer's Brigade.[96][101] McIntosh's report said his brigade (including the 18th Pennsylvania but without the 5th New York) at Yellow Tavern was only "slightly engaged".[99] The 18th Pennsylvania had one enlisted man wounded in action on May 9 and 10, and no casualties on May 11.[102]

In the pre-dawn of May 12, Sheridan's advance was caught in a fight with the Richmond fortification and Stuart's cavalry, and Wilson's First Brigade became separated from the Second Brigade that it was following in "pelting rain and howling thunder."[100] A portion of the 18th Pennsylvania found enemy infantry on two sides, and a general fight began at the bridge on Meadow Bridge Road. A major from the 18th Pennsylvania described the day as "the greatest anxiety I ever experienced".[100] Despite the anxiety, the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry had only three men wounded.[103] Merritt's 1st Division captured the bridge and drove the enemy back. Fighting renewed at Mechanicsville for a few hours, but the Confederates were driven away and Sheridan's force camped near New Bridge that evening. Over the next few days, Sheridan moved by White Oak Swamp to Malvern Hills where they were accidentally shelled for a brief time by Union gunboats on the James River. On May 15 and 16 they camped at Haxall's Landing on the James River.[104] On May 17, they moved north toward the Pamunkey River. The regiment was not involved in fighting for the next 10 days as they moved north.[105] Sheridan reported on May 20 that he found "little subsistence and forage" at White House landing (on the river) and wanted "ammunition first and supplies of all kinds".[106]

By May 27, the brigade had already returned to Grant; camped at Butler's Bridge on the North Anna River, and was rejoined by the 5th New York Cavalry.[107] During May, Wilson relieved Bryan from command of the 18th Pennsylvania because he "failed to act swiftly enough" in a small fight with Major General Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry, and Brinton became commander.[108] Casualties for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry for the period of May 22 through June 1 were two enlisted men killed, two officers and three enlisted men wounded, and three enlisted men captured or missing.[109]

Battle of Cold Harbor

The regiment fought in the Battle of Cold Harbor, which began May 31 and lasted through June 12. In this Confederate victory, the Union Army had about 12,000 casualties while the Confederates had about 4,000.[110] Much of this difference in casualties was caused by Union infantry assaults on well-entrenched enemy troops, especially on June 3.[110] On the morning of May 31, McIntosh's brigade crossed the Pamunkey River at Hanovertown and drove the enemy back toward the town.[111] Around sundown, the 18th Pennsylvania led a dismounted advance that pushed the enemy out of the town.[112] Brinton and Phillips were slightly wounded, and two captains were severely wounded.[Note 10] Brinton led the regiment and the 2nd Ohio Cavalry on a June 10 scout of Shady Grove Road, while the other half of the brigade probed Richmond Road.[114] On June 10, the 18th Pennsylvania had just established a picket line when the 9th Virginia Cavalry attacked one side. That portion of the regiment retreated in confusion, but entrenched United States Colored Troops who had been sent to support McIntosh stopped the enemy.[Note 11] Losses for the 18th Pennsylvania were described as "considerable".[116] The brigade covered the rear of the army on June 12 and June 13.[114]

Post Cold Harbor

The regiment, under Brinton's command, advanced in a move toward White Oak Swamp on June 15, and had had to fight infantry in a wooded area while unassisted. Lieutenant Samuel McCormick was killed and now-Captain Tresonthick was mortally wounded on that day at St. Mary's Church in an engagement that lasted nearly five hours.[117] Most of the June 15 fighting was dismounted, and the regiment later learned that their action was "part of the attempt to deceive the enemy, to make him believe and think that the whole army was on the north side of the James River, and would attempt to reach Richmond from that direction."[118] Casualties for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry for the period of June 2 through June 15 were one officer and two enlisted men killed, one officer and 33 enlisted men wounded, and 28 enlisted men captured or missing, with most of the regiment's casualties for this period coming on June 15.[119][120][121]

The regiment moved to the rear of Major General Horatio Wright's VI Corps on June 22. On the next day, Wilson's division departed on what would become known as the Wilson–Kautz Raid, but the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry and 3rd New Jersey Cavalry remained behind and reported to Wright.[117] An official report lists Phillips as commander of the regiment on June 30.[122] During July, the regiment spent most of its time on picket duty. On August 5, the regiment moved to City Point and boarded a steamship destined for Alexandria, Virginia. A few days later, after their arrival in Alexandria, the regiment became armed with Spencer repeating rifles.[123] They departed for the Shenandoah Valley on August 11. The rest of Wilson's division was also ordered to move to the Shenandoah Valley, and the division became part of Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah.[124]

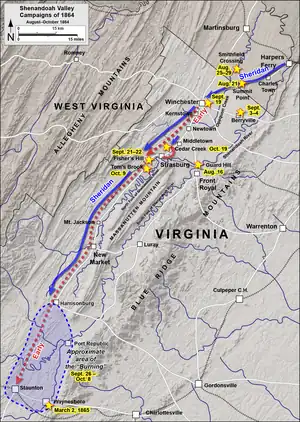

Shenandoah Valley

On July 31, 1864, Grant decided to have Sheridan be his field commander to fight Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early in the Shenandoah Valley. On August 1, Sheridan was relieved of command from the Army of the Potomac, "but not from command of the cavalry as a corps organization."[125] To satisfy the Lincoln administration's concern about Sheridan's young age, Grant intended to have Major General David Hunter be the head of an army that was the consolidation of four military districts, but have Sheridan be the leader in the field.[125][126] On August 5, Grant ordered Hunter to "Concentrate all your available force without delay in the vicinity of Harper's Ferry....", and sent him more cavalrymen.[127] Hunter asked to be relieved entirely, and his request was granted—putting Sheridan in command of the new army.[128] The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry arrived at Harper's Ferry on August 12. The regiment patrolled and skirmished on both sides of the Potomac River—including Charlestown, Bolivar Heights, and Shepherdstown in West Virginia; Berryville in Virginia; and Boonsboro and Sharpsburg in Maryland.[129] Sheridan's army began with Wright's VI Corps and three cavalry divisions. The 18th Pennsylvania remained in the same chain of command, as part of McIntosh's First Brigade in Wilson's 3rd Division, and remained under Brinton's command.[130][131]

Third Battle of Winchester

The Third Battle of Winchester, also known as the Battle of Opequon, is considered by some historians to be the most important American Civil War battle in the Shenandoah Valley.[132] A total of 54,000 men from both sides participated in this Union victory on September 19. Against Early's Army of the Valley, Sheridan had two divisions of cavalry, two infantry corps under Wright and Brigadier General William H. Emory (XIX Corps), and the Army of West Virginia, consisting of both infantry and cavalry, led by Brigadier General George Crook.[133][Note 12] Casualties for both sides totaled to over 8,600.[132]

McIntosh's brigade left camp near Berryville around 2:00 am on September 19 and moved on the Berryville Pike toward Winchester.[131] Two regiments from McIntosh's brigade, the 2nd New York and 5th New York, led the initial advance across the creek.[135] The 18th Pennsylvania and 2nd Ohio Cavalries led the rest of the brigade across and joined the two New York regiments. Enemy pickets fled through a second group of pickets that belonged to the 23rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment. Three more North Carolina Confederate infantry regiments, the 5th, 20th, and 12th, held off the New Yorkers and caused them to retreat. McIntosh responded with artillery and an attack by the 18th Pennsylvania.[136] The 18th Pennsylvania made mounted attacks on infantry breastworks.[131] The regiment's Third Battalion, led by now-Captain Britton, led the first charge followed by the Second and First Battalions. It took three charges before the 5th and 20th North Carolina Infantry Regiments were driven back to a secondary position. Brinton's horse was wounded before the final charge, and he was wounded and captured in the final charge. In describing the charges, one battalion commander said, "we lost heavily".[137] With Brinton gone, Phillips, commander of the Second Battalion, became the regiment's commander. Later in the day, McIntosh was seriously wounded leading a dismounted charge. His wound required amputation of his leg below the knee, and Lieutenant Colonel George A. Purington replaced him.[138] Casualties for the regiment were seven men killed and 12 wounded, plus one officer captured.[130] Brinton escaped in the night and returned to the regiment on the next day.[139]

Tom's Brook

On October 3, Custer took command of the 3rd Cavalry Division.[140] The division continued destroying crops, barns, and mills in the valley as it moved north, which depleted the food and infrastructure used to supply the Confederate Army. During this time, the division was followed and harassed by Confederate cavalry. On October 9, the First Brigade (now led by Colonel Alexander Pennington) took the advance in an attack against enemy cavalry.[141] At first met with "stubborn resistance", Custer sent the 18th Pennsylvania supported by two other regiments to turn the enemy's flank.[142] On Custer's command, all regiments charged—resulting in the capture of all enemy artillery, wagons, and ambulances while the enemy fled. One soldier wrote "I never saw such a complete rout in my life."[143] Custer reported "Never since the opening of this war had there been witnessed such a complete and decisive overthrow of the enemy's cavalry" and that a pursuit was made "vigorously for nearly twenty miles."[142] The battle became jokingly referred to as the Woodstock Races.[144]

Battle of Cedar Creek

The Battle of Cedar Creek was fought on October 19, 1864. In this Union victory, Early's Confederate force surprised the Union Army at Cedar Creek, Virginia, and appeared to be destined for a victory until Sheridan arrived and rallied his troops.[145] The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry was assigned the task of supporting a battery that was exchanging fire with enemy artillery, and suffered some casualties when a shell burst directly over the regiment.[144] Casualties for the regiment were one killed and six wounded.[146]

On November 12, the regiment was involved in a skirmish at Cedar Creek. Enemy cavalry drove in Union pickets early in the morning and attacked near the Union camp. Pennington's First Brigade was sent to fight the attackers.[147] Although the enemy soldiers were driven off, the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry became cut off from the brigade. Philips was commanding the regiment at the time, and Confederate cavalry under the command of Rosser captured him and 164 others.[Note 13] Phillips and Lieutenant Henry J. Blough were sent to Libby Prison in Richmond.[152] Private Nathan Monz (Company D) and Private John L. Stall (Company E) were killed—the last two soldiers in the regiment to be killed in action.[153] Pennington censured the regiment for its conduct in this action.[154] The regiment was censured again and described as setting "a very bad example to the brigade" for its action near Mount Jackson on November 22, when it left rear guard duty and "was not to be found until after the brigade was relieved from duty".[155]

Winter camp

For the next few weeks, the regiment camped near Winchester and performed picket duty and scouting tasks. A portion of the regiment went to Cedar Creek Valley to hunt bushwhackers.[154] The regiment also went on a scouting mission near Moorefield, West Virginia. In December the regiment went to Camp Remount in Pleasant Valley, Maryland. There they went into winter camp and turned in their worn-out horses. The Third Battalion received new horses while the other two battalions remained dismounted through the winter.[156] Darlington and Van Voorhis had now mustered out, and Phillips was in a Confederate prison. Captain William H. Page of Company L was promoted to major with an effective date of December 1, and twice-wounded Britton of Company F was promoted to major effective December 3. Brinton mustered out January 13, 1865.[70]

Battle of Waynesboro

While the regiment's two dismounted battalions remained in camp, the mounted Third Battalion departed from camp on February 25, 1865, and reached Winchester on the next day.[157] Sheridan had two divisions of cavalry and planned to join Grant near Richmond. The plan changed on March 2 when Sheridan's army approached Waynesboro, Virginia and found Early's Army of the Shenandoah. Custer's division did the fighting, and most of Early's army was killed or captured.[158] All of Early's headquarters equipment and artillery were captured although Early himself evaded capture.[159] The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry's Third Battalion, commanded by Captain George W. Nieman, and the 5th New York Cavalry, were held in reserve in this battle.[160]

After the battle, the battalion was part of a force that escorted about 1,600 prisoners north to Winchester.[161] On March 7 during the trip north, Rosser's cavalry attacked the Union force at Rude's Hill near Mount Jackson.[Note 14] A counterattack led by the 5th New York drove off the Confederates in hand-to-hand fighting.[162] The Union force and all prisoners arrived at Winchester on March 7. Here, they were under the command of Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, who had temporary command of Union forces around Winchester.[162]

Conclusion

For the next few weeks of 1865, the battalion camped at Kernstown near Winchester.[157] On April 9, the surrender of Lee's army was announced. The battalion went on scouting missions, guarded wagon trains, and had picket duty over the next two weeks. On April 26, the rest of the regiment returned from Camp Remount and joined the battalion. The regiment camped in Staunton, Harrisonburg, Mt. Jackson, and Cedar Creek over the next few weeks.[164] On May 5 they were joined by some of their officers who returned from Confederate prisons. Colonel Theophilus F. Rodenbough joined the regiment on May 12 and took command.[164] On the same day, Private John Kies died from wounds suffered earlier—the last soldier in the regiment to die from action.[153] For the rest of the month, the regiment moved toward Cumberland and camped nearby.[164] Portions of the regiment mustered out in early June. Company E mustered out on July 1—the same day part of Company C was put under arrest for insubordination.[165] On July 20, the 18th and 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiments were combined and became the 3rd Provisional Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment—with an effective date retroactive to June 24.[166][8] The new regiment served in West Virginia until it was mustered out of service on October 31, 1865.[166]

During the war, the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry had five officers and 55 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded. An additional two officers and 232 enlisted men died from disease.[8] Over half of the men that died from disease died in Confederate prisons, and almost two thirds of those that died in prisons died at Andersonville Prison.[153]

Notes

Footnotes

- The commonwealth (state) of Pennsylvania had a "confusing numbering system" for its American Civil War regiments.[4] Each regiment received two designations. One number reflected the order, regardless of branch, of when the regiment was raised. In the case of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, they were the 163rd regiment of any branch raised in Pennsylvania. The second number, 18th Cavalry in this example, corresponded to the regiment's integration into the Federal armed force.[4]

- Theo F. Rodenbough, former colonel of the regiment, discussed recruiting in the regimental history. He also wrote that the regiment had some professional bounty jumpers "whose interests were purely commercial and who availed themselves of the first opportunity to desert"—and this was a "frequent occurrence".[2]

- Fairfax, Virginia, is about 21 miles (34 km) from Washington, DC.[10]

- Two 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiments existed at the start of the American Civil War. The Confederate 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiment was organized in Winchester, Virginia in July 1861.[12] The Loyal 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiment was organized in Wheeling and other northwestern Virginia cities in 1861.[13] It fought for the Union and was scouting with the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry on January 11, 1863. The Loyal 1st Virginia became the 1st West Virginia Cavalry Regiment on June 20, 1863, after a portion of Virginia joined the United States as West Virginia.[14]

- Mosby identifies "Major Joseph Gilmer, 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry" when discussing Gilmore, as does Lieutenant Colonel Robert Johnstone (5th New York Cavalry) in his report.[19] Bates identifies the major as Joseph Gilmore, who was dismissed July 23, 1863.[18]

- Gilmore was court-martialed and charged with drunkenness and cowardice. Although originally sentenced to be cashiered, the proceedings were disapproved because of defects and irregularities in the record. Instead, Gilmore was dismissed (not cashiered).[22]

- Potter became Captain of Company L on April 14, 1865.[34]

- The American Battlefield Trust South Cavalry map shows the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry on the west side of the First Brigade. The 5th New York protected artillery in the rear.[47]

- Phillips' wound was not severe enough to prevent him from leading a charge on May 31.[93] Darlington survived but had a leg amputated by Confederate surgeons.[85] Several days later, he was rescued by General Sheridan while being taken to Richmond.[91] He mustered out October 3, 1864.[70]

- The regimental history mentions the officers wounded, including Brinton and Phillips.[105] Major John W. Philips is listed as commander of the regiment as of May 31 in an official report.[113] However, other reports mention Brinton leading the regiment in actions during early June.[114]

- Sources do not identify the entrenched regiments. McIntosh's report says, "I was supported by two regiments of colored troops."[114] Philips' diary says, "...the Reb Cavalry (9th Va) charged the whole right line...." and "They were stopped by the negroes in the breast works and then driven back by our cavalry."[115]

- Crooks' Army of West Virginia is labeled by some as the VIII Corps.[134] Official records list the various corps and their commanders. They also show Crooks' command as the Army of West Virginia, and its cavalry division on loan to Sheridan as the 2nd Division with General William W. Averell as commander.[133]

- Phillips wrote that he and 164 others were captured by Rosser.[148] Pennington's report listed one officer killed, three officers and 18 enlisted men wounded, and two officers and 72 men missing from his brigade, but the report does not have details for the Second Brigade.[149] The regimental history stated that Phillips, "Captain" Henry J. Blough, and "a number of men" were captured—also some killed and wounded.[150] Lieutenant Grier, also in the regimental history, wrote that Phillips and Lieutenant Blough were captured with about a dozen men. Grier also stated that the First and Second Brigades became separated when the Second Brigade was driven back, which "let the enemy get in our rear".[151]

- Boudrye spells Rude's Hill as "Rood's Hill".[162] The historian for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry spells it as "Rondes Hill".[157] Pond wrote that the attack was "near Mount Jackson".[161] A map at the Library of Congress uses the "Rude's Hill" spelling.[163]

Citations

- "Civil War Facts". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 13

- United States Adjutant-General's Office 1865, p. 790

- Gibbs 2002, p. 1869

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 34

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 14

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 180

- "Union Pennsylvania Volunteers - 18th Regiment, Pennsylvania Cavalry (163rd Volunteers)". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-02-07.

- Bates 1871, p. 1042

- Traffic Service Bureau 1912, p. 459

- Black 2008, pp. Chapter 1, 7th page, of e-book

- "Confederate Virginia Troops - 1st Regiment, Virginia Cavalry". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

- "Union West Virginia Volunteers - 1st Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

- "The New State of West Virginia". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- Boudrye 1865, p. 47

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 153

- Flemming, Hays & Hays 1919, p. 707

- Bates 1871, p. 1049

- Mosby 1887, p. 56

- Mosby 1887, p. 57

- Mosby 1887, p. 55

- Mosby 1887, pp. 59–60

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 36

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 37

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 38

- Rhodes 1900, p. 52

- Wittenberg & Petruzzi 2006, p. 70

- Boudrye 1865, p. 63

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 39

- Rhodes 1900, p. 54

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 77

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 87

- Wittenberg & Petruzzi 2006, pp. 70–71

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 265

- Wittenberg & Petruzzi 2006, p. 82

- Wittenberg & Petruzzi 2006, p. 80

- Wittenberg & Petruzzi 2006, p. 81

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 88

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, pp. 90–91

- Boudrye 1865, p. 64

- Wittenberg & Petruzzi 2006, pp. 85–92

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 78

- "CWSAC Battle Summaries: Hanover". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- Scott 1889, p. 1008

- Boudrye 1865, p. 66

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 40

- "Gettysburg - South Cavalry Field". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- Collea 2010, p. 171

- Starr 2007, p. 441

- Collea 2010, p. 176

- Collea 2010, p. 182

- Scott 1889, pp. 1018–1019

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 84

- "Gettysburg". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 3

- Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 39

- Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 65

- "Battle Detail - Williamsport". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 85

- Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 115

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 93

- Wittenberg 2011, Ch. 16 of e-book

- Boudrye 1865, p. 74

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, pp. 42–43

- Scott 1890, p. 212

- "Bristoe Campaign". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- Scott 1890, p. 224

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 44

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 19

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 181

- Scott 1890, p. 389

- Scott 1890, p. 386

- Scott 1890, p. 388

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 45

- Scott 1890, p. 663

- Scott 1890, pp. 675–676

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 46

- "Ulysses S. Grant". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- Gallagher 1997, p. 85

- Rhea 2004, p. 40

- Boudrye 1865, p. 119

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 49

- Boudrye 1865, pp. 121–122

- Gallagher 1997, p. 108

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 50

- Gallagher 1997, pp. 117–118

- Gallagher 1997, p. 118

- Gallagher 1997, pp. 119–121

- Gallagher 1997, p. 121

- Gallagher 1997, pp. 121–122

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 21

- Rhea 2004, p. 257

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 24

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 22

- "Spotsylvania Court House". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 51

- Scott 1891, p. 64

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 101

- Scott 1891, p. 887

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 102

- "The Fall of the Rebel Cavalier". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Scott 1891, p. 184

- Scott 1891, p. 185

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 103

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 52

- Scott 1891, pp. 779–780

- Scott 1891, p. 888

- Rhea 2000, p. 401

- Scott 1892, p. 164

- "Cold Harbor". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- Scott 1892, p. 888

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 104

- Scott 1891, p. 208

- Scott 1892, p. 889

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 105

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 53

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 25

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 105

- Scott 1891, p. 178

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, pp. 105–106

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 107

- Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1892, p. 551

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 56

- Boudrye 1865, pp. 162–163

- Sheridan 1992, pp. 461–463

- Bluhm 2014, pp. 40–41

- Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1891, p. 26

- Sheridan 1992, pp. 465–466

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, pp. 56–57

- Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 117

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 57

- "Battle Detail – Opequon". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, pp. 112–118

- "American Battlefield Trust - Battle of Third Winchester (Opequon)". American Battlefield Trust - Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Boudrye 1865, pp. 172–173

- Patchan 2013, Ch.13 of e-book

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 111

- Patchan 2013, Ch.20 of e-book

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 129

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 59

- Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 520

- Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 521

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 116

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 60

- "CWSAS Battle Summaries - Cedar Creek (archived)". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2006-02-21. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 137

- Boudrye 1865, p. 184

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 120

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 125

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 63

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 119

- Phillips & Athearn 1954, p. 121

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, pp. 137–156

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 64

- Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 534

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 65

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 66

- "Remembering the Battle of Waynesboro". Waynesboro Heritage Museum. 21 July 2013. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- Boudrye 1865, p. 191

- Davis, Perry & Kirkley 1894, p. 505

- Pond 1912, p. 253

- Boudrye 1865, p. 193

- "Nos. 38-38a: Rude's Hill Action, Mount Jackson, Virginia". Library of Congress. United States Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 67

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 68

- Rodenbough, Potter & Seal 1909, p. 71

References

- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1902). The War of the Rebellion : A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I – Volume LV. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057.

- Bates, Samuel P. (1871). History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5; Prepared in Compliance with Acts of the Legislature. Harrisburg, PA: B. Singerly, State Printer. OCLC 1887553.

- Black, Robert W. (2008). Ghost, Thunderbolt, and Wizard: Mosby, Morgan, and Forrest in the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. OCLC 681219923.

- Bluhm, Raymond K. (2014). The Shenandoah Valley Campaign: March-November 1864 (PDF). Washington, District of Columbia: Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 978-0-16092-433-0. OCLC 890726898. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- Boudrye, Louis N. (1865). Historic Records of the Fifth New York Cavalry, First Ira Harris Guard: Its Organization ... and General Services, During the Rebellion of 1861-1865, with Observations of the Author by the Way, Giving Sketches of the Armies of the Potomac and of the Shenandoah ... Albany, NY: S. R. Gray. OCLC 558081147.

- Collea, Joseph D. (2010). The First Vermont Cavalry in the Civil War: A History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-786-43383-4. OCLC 461895538.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1891). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XLVI Part I Reports. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 318422190.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1892). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XL Part II Correspondence, Etc. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057.

- Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1894). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume LVIII Part I Reports. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057.

- Flemming, George Thornton; Hays, Gilbert Adams; Hays, Alexander (1919). Life and Letters of Alexander Hays, Brevet Colonel United States Army, Brigadier General and Brevet Major General, United States Volunteers. Pittsburgh, PA: [Not Listed]. OCLC 166608086.

- Gallagher, Gary W. (1997). The Wilderness Campaign. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80783-589-0. OCLC 1058127655.

- Gibbs, Joseph (2002). Three Years in the "Bloody Eleventh": The Campaigns of a Pennsylvania Reserves Regiment. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-27102-166-9. OCLC 248759378.

- Mosby, John S. (1887). Mosby's War Reminiscences, and Stuart's Cavalry Campaigns. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead & Company. OCLC 11269959.

- Patchan, Scott C. (2013). The Last Battle of Winchester: Phil Sheridan, Jubal Early, and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, August 7-September 19, 1864. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-98-2. OCLC 751578151.

- Phillips, John Wilson; Athearn, Robert G. (1954). The Civil War Diary of John Wilson Phillips. Richmond, VA: The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 62, No. 1. pp. 95–123. OCLC 14155199.

- Pond, George E. (1912). The Shenandoah Valley in 1864. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 13500039.

- Rhea, Gordon C. (2000). To the North Anna River Grant and Lee, May 13-25, 1864. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-80714-069-7. OCLC 1058861952.

- Rhea, Gordon C. (2004). The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5-6, 1864. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-80713-021-6. OCLC 70080406.

- Rhodes, Charles D. (1900). History of the Cavalry of the Army of the Potomac including that of the Army of Virginia (Pope's) and also the History of the Operations of the Federal Cavalry in West Virginia During the War. Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-84677-505-5.

- Rodenbough, Theophilus F.; Potter, Henry C.; Seal, William P. (1909). History of the 18th Regiment of Cavalry Pennsylvania Volunteers (163 Regiment of the Line) 1862-1865. New York, NY: Winkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co. OCLC 6315612.

- Scott, Robert (1889). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 191710879.

- Scott, Robert (1890). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXIX Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 318422190.

- Scott, Robert (1891). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVI Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 3888071.

- Scott, Robert (1892). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XLVIII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057.

- Sheridan, Philip Henry (1992) [1888]. Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan, General, United States Army. Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Pub. ISBN 978-1568370-48-4. OCLC 27574500.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (2007). The Union Cavalry in the Civil War - Vol. 2 - The War in the East, from Gettysburg to Appomattox. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 4492585.

- Traffic Service Bureau (1912). Public Service Regulation, Vol. 1 July. Chicago, Illinois. OCLC 1569043. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - United States Adjutant-General's Office (1865). Official Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army for the Years 1861, '62, '63, '64, '65 (Part III). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 686779.

- Wittenberg, Eric J.; Petruzzi, J. David (2006). Plenty of Blame to Go Around : Jeb Stuart's Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. New York, NY: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-017-0. OCLC 759859025.

- Wittenberg, Eric J.; Petruzzi, J. David; Nugent, Michael F. (2008). One Continuous Fight: the Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July 4–14, 1863. New York, NY: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-9327144-3-2. OCLC 185031178.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. (2011). Gettysburg's Forgotten Cavalry Actions: Farnsworth's Charge, South Cavalry Field, and the Battle of Fairfield, July 3, 1863. New York, NY: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-071-2. OCLC 779472347.