1877 U.S. Patent Office fire

The Patent Office fire of 1877 was the second of two major fires of the U.S. Patent Office. It occurred in the 1864 Patent Office Building of Washington, D.C., on September 24, 1877. The building was constructed to be fireproof, but many of its contents were not. About 80,000 models and 600,000 copy drawings were burned to some degree. No patents were completely lost, however (unlike the situation with the first Patent Office fire), and the Patent Office was soon reopened for recordings.

Patent Office 1877 fire | |

| Date | 24 September 1877 |

|---|---|

| Location | U.S. Patent Office, Washington, D.C., USA |

| Coordinates | 38.89778°N 77.022936°W |

| Outcome | Entire west and north wing of Patent Office building burnt. |

History

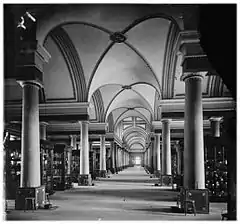

On July 4, 1836, the Patent Office became its own organization within the Department of State under the Patent Act of 1836. Henry Leavitt Ellsworth became its first commissioner. He started construction of a new fire-proof building, after the previous building had burned down in a disastrous fire. Architect Robert Mills was given instructions by Congress to design the building using fireproof construction material.[1] Mills used masonry vaulted ceilings that spanned the interior spaces for an open floor plan, cement plastered walls, and cantilevered stone staircases from floor level to floor level.[1] Construction of the building was finished in 1864.[2]

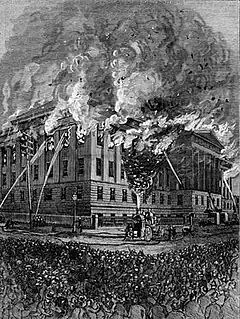

The Patent Office fire started at about 11 am on September 24, 1877. It was reported in the newspaper that the fire started in the room that held the patent models.[3] There was a considerable amount of flammable material in that area. Spontaneous combustion of patented chemicals has been given as one of the theories for the start of the fire.[4] Another theory was that a lens might have caught the sun's rays and focused them on a combustible object. Others claim that it was an unseasonably cold morning, and that a fire started by some copyists in their office grate emitted sparks that fell onto the roof and caught a wooden gutter screen on fire. The roof was constructed of wood, which led to a rapid ignition and a fast-moving disastrous building fire.[3] The fire burned part of the upper portions of the north wing and the west wing, consuming half the building.[5]

The Evening Star reported that the spectacle of the building going up in flames became extraordinarily shocking to the spectators as it turned into a calamity. Despite the fire-proof construction efforts the fire consumed the building and devoured some 87,000 patent models with their associated documents. Some of the important artifacts were saved, however, due to the extraordinary efforts of the Patent Office staff and some valiant firemen.[6]

Models destroyed

This second Patent Office fire was even more destructive than the first fire in 1836 at Blodget's Hotel. According to the person in charge of the models, about 87,000 models were burned to one degree or another and some 600,000 photo-lithographic drawings were damaged by fire and or ruined by water.[7] Although the building may have been considered fire-proof, the contents were not. An early part of the conflagration was a storage room used for rejected and postponed models.[8] There were 37,000 postponed application models and 12,000 rejected cases, making the total damage tally around 136,000 patent models (of one type or another). The monumental building cost almost $3,000,000 in nineteenth-century dollars.[9] A source reported the loss due to the fire as over a half a million dollars in value.[10]

The Patent Office could loan out the rejected models to museums and other organizations; however, due to future potential patent infringement they were against such transfers to preserve the integrity of the inventor's idea. These models included metal-working machines, wood-working machines, agricultural implements, carriages, wagons, railroading, mechanical, hydraulic and pneumatic engineering. An example of the original Eli Whitney cotton gin was among the representative models destroyed. In the south and west wings of the Patent Office there were some 100,000 models that were not damaged. Reports of the time show about two-fifths of all the models were damaged either by fire or water. An estimated 200,000 drawings were hastily carried out of the building before they were damaged.[5]

In spite of these great monetary losses (many times those of the first Patent Office fire of 1836), there were no patents totally destroyed in the fire.[11] There were duplicates of the drawings (a lesson learned from the first Patent Office fire in 1836) and it was just a matter of printing them again.[12] Despite the loss of the upper floors and some accumulated trash, the Patent Office was soon reopened.[4]

References

- Goodheart (2006), p. 3.

- Keim 1874, p. 29.

- "U.S. Patent Office on fire". Harrisburg Telegraph. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. September 24, 1877. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Patent Materials from Scientific American, The Fire in the U.S. Patent Office". Scientific American. Vol. 37 new series - issue Jul 1877 – Dec 1877, no. 15. 13 October 1877. p. 224. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- "Patent-Office Fire". Harper's Weekly. October 13, 1877. pp. 809–810.

- Goodheart (2006), p. 4.

- Campbell 1891, p. 89.

- "Models destroyed by the fire at the American Patent-Office". The Engineer. 44: 304. October 26, 1877. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Report of the investigation of the United States Patent office made by the President's commission on economy and efficiency. United States - President's Commission on Economy and Efficiency. December 1912. pp. 131–132. Previous to the occurrence of the fire the Patent Office Building had been looked upon as a fireproof structure.

- Harte 1914, p. 237.

- Niemann 2006, p. 130.

- Dobyns 1994, pp. 184–192.

Sources

- Campbell, Levin H. (1891). The patent system of the United States, so far as it relates to the granting of patents. Washington D.C.: McGill and Wallace. OCLC 1137224127.

- Dobyns, Kenneth W (1994). The Patent Office pony. U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-9632137-4-7.

- Goodheart, Adam (July 2006). "Back To The Future: One of Washington's most exuberant monuments—the old Patent Office Building—gets the renovation it deserves". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- Harte, Bret (1914). The writings of Bret Harte. Houghton, Mifflin & Company. OCLC 13326922.

- Keim, DeB Randolph (1874). Keim's Illustrated Guide to Museum of Models, Patent Office. U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 681967046.

- Niemann, Paul (2006). More Invention Mysteries. Quincy, IL: Horsefeathers Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-9748041-1-8.